By James T. Bartlett

The book starts with Cecil’s wife Diane, 30, banging on the door of a neighbor, screaming for help. Her face bloodied and bruised, she gasped that two men had broken into their apartment, shot Cecil while he slept, beaten her, and escaped with money and jewelry.

The police thought it was a robbery turned violent, but then they got a tip that Diane was having an affair.

Her alleged paramour was Johnny Warren, a married musician who worked the local clubs – and who was Black. In Jim Crow America, this was sensational and scandalous; more so since it had happened in far-off Alaska, then a US territory.

At the time, Alaska was largely ignored by the rest of the country, yet this story exploded onto the pages of Life, Newsweek, Ebony, Jet, the pulp detective magazines, and newspapers in what Alaskans still call the “Lower 48”.

As the investigation began, abrasive Chief of Police EV Danforth, just a few months into the job, knew it could make – or finish – his career. So did the newly-appointed US State Attorney for Fairbanks, Theodore “Ted” Stevens.

The pair soon butted heads, especially when – as often happens – other law enforcement agencies became involved (in this case the Territorial Police, the US Marshals Service, and the FBI).

Cecil Wells had just been elected the head of the All Alaska Chamber of Commerce, and he and Diane were what we’d now call a “power couple.” They were due to be in Anchorage, celebrating the opening of its international airport, and the fact that, instead, his murder was the main headline in the Anchorage Daily Times, showed just how big a deal it was.

Danforth and Stevens needed quick results, especially since many had noticed this was similar to the case of Tommy Wright, who had also been killed by two robbers in his home earlier in the year. The Wright case was still unsolved.

There were soon plenty of theories about who killed Cecil, including a whisper about organized crime, but Diane always stood by her statement, despite the fact it turned out to have plenty of holes: i.e. if it was professional hitmen, why leave her alive to tell the tale?

Moreover, her staunch denial of a love affair was disproved when romantic letters emerged, nor was there any sign of a break-in at the Wells’ eighth-floor apartment. The “missing” money and jewelry turned up too – though the murder weapon never did.

Warren and Diane were both charged with first-degree murder by Stevens, who, despite being looked on initially with suspicion as an outsider or “cheechako” had won quick friends, including the editor of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, by trying to reintroduce the “Crime Squad.”

A roving group of Alaskan law officials, the “Squad” came down hard on Fairbanks crime, even the often-tolerated ones like gambling, illegal liquor, and prostitution. The army, whose base populations dwarfed that of the locals, were also keen to crack down on anything illicit.

Stevens always denied the story that he led some raids visibly armed, while many others resented his trying to spoil their fun in what was, for all its undoubted beauty, a tough and difficult place to live.

Danforth rallied hard against it too, and since Cecil’s murder had happened in the Northward Building, right in the center of downtown Fairbanks, he felt it was very much a job for the city police, with him calling the shots.

That said, his control of the crime scene was poor, with vital potential evidence missed, and his decision to get fingerprints analyzed at a local hospital – instead of sending them straight to the FBI – was an attempt for an early personal win, but ended up wasting time and money.

Danforth knew that being the Chief of Police was a poisoned chalice. Alaska had just come under control of the Bureau of Prisons, and their first report about what they had found was, understandably, blisteringly critical (and it wasn’t until 2021 that Fairbanks got their first CSI officer – also Alaska’s first, too).

In the end, Danforth lost the confidence of city officials and the public, resigning barely six weeks after Cecil Wells’s murder, and leaving Stevens to take center stage – for good or bad.

Cecil’s family were so unhappy they hired private detectives to look into the case, but even today, they still knew little about the investigation. They told me it had always been a taboo subject, and after mentioning bitterly how the lawyers “got everything,” a couple mentioned how it was “swept under the carpet,” quietly forgotten as a sacrifice for the greater good of statehood.

Alaska only joined in 1959, and it rankled with many that Congress resisted Alaska’s charms for so many years, despite the crucial role that it played in WWII and the subsequent Cold War. Even with its assets of fur, forestry, fishing, gold and other resources, there had been strong resistance to giving the vast, sparsely-populated territory one of the precious stars.

Now Cecil Wells was the latest high-profile (meaning: rich) victim of a deadly home invasion, and the people of Fairbanks – especially those in that social bracket – were scared and angry, especially since this case was making all the wrong kind of headlines in the Lower 48.

It was not, as we would say today, “good optics,” and things got worse when – despite rewards being offered for the killers of Wright and then Wells – heating oil distributor and car rental agency owner George Nehrbas and his wife were attacked at home by two men, one of whom actually mentioned Wright and Wells, saying: “You are going to be next.”

Was a gang targeting the rich, and getting away with it? Perhaps the great and the good in distant Washington, DC, were asking: “What are the police doing? Isn’t Fairbanks one of Alaska’s big cities?”

That said, even when the trail became cold, Stevens never gave up on Cecil’s case. Perhaps with an eye to his future career, he seemed determined that someone, anyone, should go to jail, and in 1955 he secured an unlikely conviction for perjury against William Colombany, a Guatemalan dance teacher who knew Cecil and Diane.

US Deputy Marshal Frank Wirth, who was involved with the investigation from the beginning, had earlier taken the unusual step to publicly name Colombany as the “third suspect,” and the rumor mill had churned when Colombany followed Diane and her three-year-old son Mark down to California.

The charge was that Colombany had tried to influence someone’s testimony in the upcoming Diane/Johnny trial, though that 1954 trial had never happened, because Diane had committed suicide in a Hollywood hotel a month before it was due to begin.

Her death made international headlines, especially when people read that Diane had written she preferred suicide to seeing her and Cecil’s son Mark, enduring the humiliation of a trial.

When it was revealed that Stevens was already certain the trial was going to be postponed it was another black eye for him, and perhaps for Alaska. If there ever a moment when Washington, DC, took notice and stared disapprovingly, this may have been it.

In 1956 it was announced that Warren was finally going to trial, but a postponement followed just as quickly, and soon after Stevens resigned and moved to Washington, DC, to pursue an opportunity at the Interior Department. He became a prime mover in the successful statehood bid, and it was the beginning of a long, illustrious (and sometimes controversial) political career.

Unsurprisingly, he never spoke publicly about the Cecil Wells murder, and Wirth’s private notes, which were given to me by his daughters, included part of a telephone transcript where Stevens admitted that the odds of convicting Warren were only ever 50% at best.

As for Wirth, he thought Johnny Warren was innocent of the murder, and stated this to reporters with Warren actually by his side after he had accompanied him on an extradition back from Oakland, California.

To their credit – and perhaps to show that Alaskan justice would be served, even if it took time – the Fairbanks Police Department continued to work the case, even when they only had Warren to prosecute. However, the FBI and police files of their efforts make it clear they were never going to bring the case to book, no matter how many rusty, old guns and bullets they sent for comparison analysis.

Wirth had a private theory about where the murder weapon, determined to be a Beretta .380, had probably ended up, and the case remains officially unsolved, though I do discuss all the possible theories in The Alaskan Blonde, with the last chapter saying what I think happened in the early hours of October 17, 1953.

Warren, who had been openly supported by Fairbanks locals during the years after the murder, still must have felt like the Sword of Damocles was hanging over him – at least until October 1960, when he was fully exonerated (after Alaska had gained statehood, you note).

We will never know whether Cecil’s murder affected Alaska’s fight for statehood, but I can say for certain that, like all violent crime, it caused generational trauma for the members of both Cecil and Diane’s families.

About the Author: James T. Bartlett is an Anthony Award-nominated and National Indie Excellence Award Winner. He is originally from London, but has been living in Los Angeles since 2004. As a travel and lifestyle journalist and historian, James has written for a number of publications including the Los Angeles Times, BBC, Crime Reads, American Way, The Guardian and Real Crime among others.

The Alaskan Blonde: Sex, Secrets, and the Hollywood Story that Shocked America

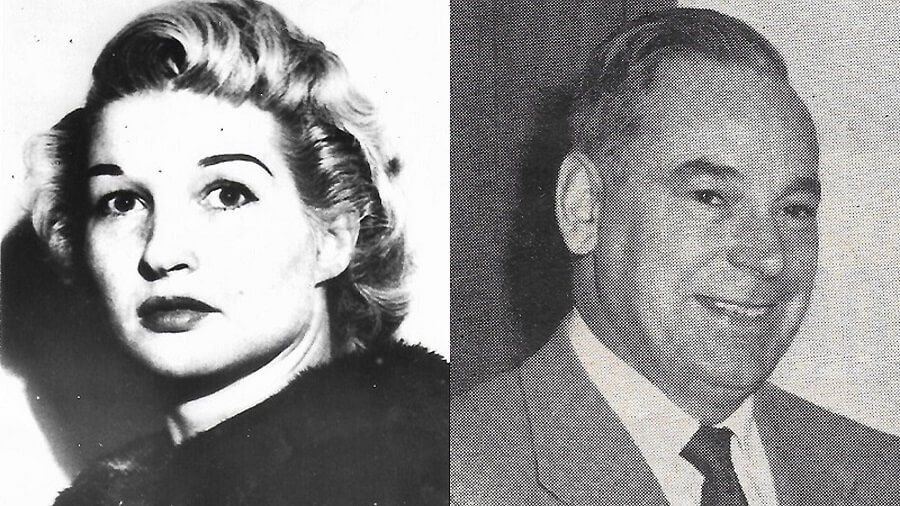

“Nicknamed “the most beautiful woman in Alaska,” 31-year-old Diane Wells was bruised and bloodied when she screamed for help in the early hours of October 17, 1953. Her husband Cecil, a wealthy Fairbanks businessman, had been shot dead, and she claimed they were the victims of a brutal home invasion.

Blonde, glamorous, and 20 years younger than Cecil, police were immediately suspicious of Diane’s account. Nearly 70 years later, journalist James T. Bartlett uncovers new evidence including an unpublished memoir, unseen photographs, and re-examines the FBI files. He tracks down and interviews the people close to Cecil, Diane, Johnny, and the mysterious “Third Suspect”, dance instructor William Colombany, to reveal the story of “the most notorious and baffling murder in the history of Fairbanks.”