Written by true crime historian Paul Drexler

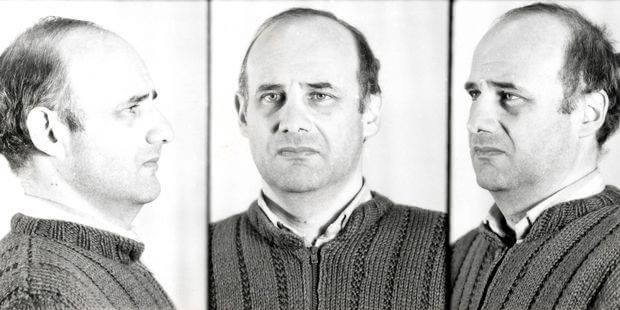

Jean Claude Romand was born in 1954 in Clairvaux-Les-Lacs, a town of 1,100, located near the border with Switzerland. His father was a respected manager of a timber farm and his mother was a homemaker. His childhood was happy, marred only by his concern about his mother’s health, and his desire not to worry her. The primary messages he received were “be honest” and “don’t disappoint people.”

Jean Claude did well academically at a private prep school, where he rubbed shoulders with wealthier children and became aware of the class system. The topic of his baccalaureate essay was “Does Truth Exist,” a subject he spent his life challenging.

Romand entered the forestry school, which his father had attended, but dropped out after a series of sinus infections. Using sickness as an excuse became a common pattern for him.

Romand’s decision to enter medical school may seem strange, since had no interest in caring for people and was repulsed by the thought of close contact with the sick. But he was attracted to the status of doctors, and to a distant cousin, Florence, who was studying medicine. Florence was not immediately attracted to him. Jean Claude was quiet and not physically attractive, but he was smart, sincere, and her parents liked him. So eventually Florence became his girlfriend.

Luc Ladmiral, another medical student, befriended Romand who was accepted into Lac’s group of friends.

The Snowball Lie

“A lie is like a snowball. The further you roll it the bigger it becomes.”

– Martin Luther

Romand did well in his first year of medical school but during the second year, Florence pulled back from their relationship, preferring to be friends rather than sweethearts. Romand was devastated. He missed his second-year examination, then scheduled a make-up exam, which he also missed. But instead of taking the test again, Romand did nothing.

Three weeks later, when the results were announced, Romand declared that he had passed the test, To his astonishment, his lie went unchallenged and everyone believed his claim.

Early success, for some, is a harbinger of addiction and downfall. You win a large sum of money the first time you go to a casino and sense that the gods are with you. You take your first sniff of cocaine and feel invulnerable. You get away with your first lie and start to believe reality can bend to your will. The more you lie, the easier it gets, and the more necessary, it becomes to continue. But each lie triggers a new question necessitating a new lie to keep the illusion intact.

After his lie was accepted, Romand fell into a kind of collapse. He stayed in his apartment for weeks, ate nothing but canned food, and gained 45 pounds. He was rescued by a visit from Luc Ladmiral who would be his best friend. Luc was a natural leader, from a well-established family of doctors. Although Romand was regarded as a country “hick” by some, Ladmiral saw him as a quiet and loyal intellectual.

In order to explain his burnout, Romand told Luc that he had lymphoma, a type of cancer. It was a clever and flexible lie since lymphoma is a disease that can lie dormant for years, without symptoms. Luc promised to keep Romand’s illness a secret.

Each year Romand was able to re-enroll as a student in his second year and he pretended to be completing his medical degree by studying for tests with his contemporaries.

After many years, someone in the medical school got suspicious so Romand pretended to graduate. Graduating, in reality, as an MD was Luc Ladmiral. Florence received a pharmacological degree.

After passing the medical board examination, Romand was “assigned,” as a research scientist, to the World Health Organization (WHO). Through Romand’s continued persistence, Florence agreed to marry him.

In 1975, Romand moved into a new role, that of research doctor, husband, and future father. He joined a group of young professionals, including Luc and others. He and Florence moved into a studio apartment. As years went on, and their careers progressed, his friends had children. They bought houses, needing greater space to accommodate their growing families.

Jean Claude’s position was prestigious but fictional and did not pay him actual money. He survived financially by selling the apartment his parents had bought for him in medical school, and he began taking money from his parents’ accounts. They didn’t seem to notice or care. But with two children, Carolyn and Antoine, to support, he needed more money.

A con man never asks for money; he creates a situation where people want to give it to him. Romand let it be known that his position as an international civil servant gave him the opportunity to make secure swiss bank investments which paid 18% a year. In 1985 Romand agreed, as a favor, to invest 380,000 francs (worth $190,000 today) of his father-in-law’s money in the bank. The investments were in John Claude Romand’s name. Over the next eight years, he embezzled an additional 800,000 francs from his parents and his uncle.

Romand’s persona was designed to support his deception. He was seen as a brilliant researcher and friend to prominent scientists and politicians. To avoid scrutiny, he shifted attention from himself, which made him appear modest, and a bit eccentric.

Romand was adamant about keeping his work and his private life completely separate. Neither his wife or his friends knew his office phone number. If his wife wanted to contact him, she would leave a message with his answering service and he would call her back later in the day. None of his friends or family ever met any of his colleagues at the World Health Organization.

In the morning Romand played the devoted father, dropping off his children at school. He then drove across the border to WHO headquarters in Switzerland. He would visit the library and other public places and take any free WHO information he could find. In later years he would often pull his car to the side of the road and read magazines, or medical journals.

When he claimed to be traveling abroad for a conference, Romand would stay in a hotel near the airport. He would research the city he was supposed to be visiting. During the “trip” he would call his family, discuss the weather in the place he was visiting, and tell everyone how much he missed them. When Romand returned he would bring back souvenirs that he purchased at the airport gift shop.

In 1989, Romand fell in love with Corrine Hourtin, the ex-wife of one of his friends. When he visited her in Paris he tried to impress her by staying in five-star hotels and buying her expensive gifts. This romance put added strain on Jean Claude’s finances.

During their relationship, Corrine sold her dental practice for 900,000 francs. She agreed to let Romand invest her money on the promise that she could retrieve it whenever she wished.

By now Romand’s life was beginning to come apart. When his father-in-law, Pierre Crolet, asked for some of his money back in order to buy a new car, Romand stalled. He visited Pierre, whose house was undergoing construction. During this visit, when they were alone, Pierre mysteriously fell and died.

Exhausted, Romand told Florence about his Lymphoma, and spent days, shivering and sweating in bed. Corrine called and demanded her money back. The pressure intensified.

The final denouement occurred when Romand took a sortie into real life. Upon his wife’s suggestion, Jean Claude joined the board of the parents’ association at his children’s private school.

When a scandal occurred at the school, the board, with Romand’s agreement, voted to demote the principal.

Knowing that his wife, Florence, supported the principal, Romand lied and told her that he had voted against the board. Romand then took an active role in supporting the principal. These were critical errors. Romand had lied in front of numerous people and the lie he told could be easily checked. Other parents on the board were furious with Romand and one threatened to punch him in the nose. For Romand, a physical coward, this was almost an existential threat.

When Florence learned from Luc that Jean Claude had lied to her, her world changed instantly.

If the man whose words she had always believed implicitly had lied about something this important, what else had he been lying about? Faced with his wife’s suspicion and his impending financial collapse, Romand completed his criminal journey from swindler to a more sinister one, known in crime terminology as a “family annihilator.”

Family annihilators tend to be highly educated men who are seen as hard-working and loving husbands and fathers. A subgroup of this type are called civic reputable, altruistic killers.

“I killed Florence to protect her from the intolerable pain she would have suffered after my suicide, said Romand. “Then I had to kill the children. Where would they have been without their parents?”

Romand was altruistic in the same way as soldiers who claim that they had to burn down a village to save it.

Romand borrowed a rifle from his father, then purchased a stun gun, tear gas canisters, cartridges, and a silencer for the rifle. The next day he took his children to school, did some errands, filled up two canisters with gasoline from a service station, and picked up his children. After the children went to bed he joined Florence on the sofa. Romand remembers nothing from this point, but they apparently had a bitter argument. His wife, Florence, who rarely drank, had enough wine to pass out. Romand stayed up all night trying to figure out what to do. At dawn, he bashed Florence’s head in with a rolling pin he had purchased the previous day.

When his children woke up Romand told them their mother was still sleeping and they watched cartoons and had cereal for breakfast. He took Caroline upstairs to her room, telling her that he wanted to take her temperature. He had her lie face down on the bed. Then he shot her in the back of the head. He repeated the process with her younger brother Antoine.

Romand returned the rifle to his car and drove to his parent’s house. He had always been seen as a model son by the community; a prestigious, busy scientist, who visited his parents faithfully each week. He took his father upstairs, telling him that he wanted to check out a faulty air vent. As his father knelt down to reach the vent, Romand shot him in the head. Romand went down the stairs and shot his mother. Romand then shot the family dog as it ran back and forth in confusion. He covered his mother with a green bedspread and put a green eiderdown over the dog.

“The family murderer usually kills each member of the family, sometimes including the pets of the house. In most cases, he will commit suicide after the killings.”

– (Park Dietz, 1986)

After killing his family, Romand called Corrine, promised to return her money, and invited her to have dinner with Bernard Kouchner, founder of Doctors Without Borders and Minister of Health For years Romand had claimed to be a close friend of Romand. While driving in the forest, Romand pretended to be lost and stopped the car. He sprayed Corrine with tear gas and tried to strangle her.

But when she pleaded and looked Romand in the eye he lost his nerve and blamed his disease for the attempt. She agreed not to tell the police.

After this failed attempt Romand returned to his home, deciding to end it all. But he managed only a poor simulation. He poured gasoline through the house, but instead of taking a lethal mix of drugs, he swallowed twenty Nembutal tablets that were over ten years old. At 4:00 AM, about the time that the early morning cleaners were starting, he started the fire on the top floor.

He returned to the second floor and laid down next to Florence, but as the smoke reached him, he staggered over and opened the window. The firemen, who were already there, heard the sound and went to rescue him. Romand spent three days in a coma.

The Movie: The Adversary (2002)

The movie, The Adversary, gives you a sense of what life is like through the eyes of an imposter, and of the concentration and effort necessary to maintain a false life

We experience the pressure Romand feels as his contemporaries move into larger homes and buy newer cars. His friends joke about him being cheap or having a secret mistress.

Romand’s carefully created persona gave him cover. He was a scholar, indifferent to material things. He wanted his family to understand the value of money. Also, his job might require him to move soon and he didn’t want the hassle of buying and selling a house. But his wife gradually agreed with his friends and began putting pressure on Romand to buy a house.

To avoid suspicion, he knew he might have to buy a house that he could not afford and just hope to increase his income. Fortunately, for Romand, he received more money from his family to invest and his scam continued.

The movie often shows Jean Claude in his car, at the side of a road, reading, or just staring into space, decomposing, as a stage actor with a challenging role might do in his off time. Is he thinking, or does he have no thoughts without an identity to play?

The movie goes back and forth in time with an occasional snippet of his video confession interspersed.

Romand has no inner life. All of his senses are externally focused. “Where is the next threat coming from? What is the response that will reassure this person and make them continue to like me..”

As his world slowly collapses around him the killings seem inevitable.

The movie ends during Romand’s trial, where he was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years to life.

Many of the observers and judges at the trial were amazed at how long Romand’s impersonation lasted. One possibility could be the Domino Theory, a classic explanation used in accident investigations. The domino theory explains that accidents are not caused by a single mistake but are rather the result of a chain of events, each dependent on the previous one. Think of a set of six dominos. Each domino has to knock down the succeeding domino for the sequence to continue.

If the third domino is removed, the sequence ends. Here are some of Romand’s dominos

Romand’s friendship with Luc Ladmiral

As his best and oldest friend Luc played a significant role in Romand’s imposture.

Luc was a highly respected physician from a well-established family of doctors. Luc looked beyond Romand’s, rural awkwardness, In medical school and saw a man of intelligence, character, and loyalty. Blinded by his own honesty, Luc did not recognize the inconsistencies that a more worldly person would notice.

The credulity and trust of Romand’s friends and family

The number of potential red flags Romand’s family and friends ignored over the years is staggering.

How many wives would be content not to know their husband’s work phone number, never meet or even speak to a single one of his colleagues, never go to a company function, and never visit their husband’s workplace in eighteen years?

How many people would invest money, even with a close relative, and never receive a single document, never ask for any specific information,

Romand’s ability to lie

A defining nature of pathological liars is that they will lie even when it has no benefit for them. Since childhood, Romand had been more comfortable with a story than with the truth. His fake identity contained many elements that were part of his inner nature. He was a listener, a follower, who shunned the spotlight but he was clever enough to give the impression of a modest but brilliant man.

While his medical credentials were counterfeit his medical knowledge was not. In conversation, he often impressed real medical specialists with his understanding. He had a con artist’s facility to read and manipulate people and the ability to get people to like him.

When Romand’s medical identity dissolved he took on a new one, sinner; but with an explanation. While Romand admitted committing the crimes, he avoided taking responsibility for them.

“An ordinary accident, an injustice can bring on madness,” Romand had written. Not explained was the nature of the accident or injustice that had led to his madness. Romand acted as if he also was a victim rather than the agent of the crimes. As if his crimes were the result of some inexplicable madness that had befallen him. It was another form of Romand’s favorite excuse, illness.

The facts of the case, however, the decades of deceit, and the careful planning of the crimes, made an insanity defense impossible.

Jean Claude Romand’s case has been a windfall for psychology, medicine, philosophy, and literary graduate students, in search of a graduate thesis.

To this day, psychiatrists have not agreed on a determination.

During the trial a panel of four psychiatrists examined Romand. He didn’t fit into any category and in the end, the doctors could not agree on a classification. He didn’t have the ego or arrogance characteristic of a narcissistic personality disorder and lacked the social withdrawal and flat affect commonly found in Schizoid personality disorders.

Romand‘s case has enabled philosophers to opine convincingly on the nature of identity and reality.

Rene Descartes, who pondered the difference between wakefulness and sleep, might have contemplated whether Romand was dreaming his life while the rest of us have been living ours.

An appeals court granted parole to Romand in 2019 and he was released into the custody of a Benedictine monastery. Since then he has been involved in prayer and charitable work.

“Romand is reputed to suffer from narcissistic personality disorder,” reported a psychiatrist.

The most inaccurate part of this diagnosis is the idea that Romand is suffering.

The role of a penitent sinner, humbly trying to expiate his crimes is one which Romand plays with absolute sincerity. And why not. He’s gotten the life he only pretended to have.

Before, Romand was a fake healer, receiving the respect and affection of others around him. It was all based on a lie.

Now, Romand is a real healer earning the respect and affection of a growing fan base of earnest Christian volunteers. This time it is based on a different lie.

“To think that it should have taken all these lies, those random accidents, and that terrible tragedy so he might do all the good he does around him,” declared a church volunteer.

Replace “random accidents” with “stealing from his family”, and ” that terrible tragedy” with “ brutally murdering his wife, his children, and his parents” and the meaning is quite different.

To those who believe that “everything happens for a reason”, Romand’s story is inspiring. To the friends and family of the people whose lives Romand has destroyed, the story is horrifying.

About the Author: Paul Drexler is a writer and crime historian in San Francisco. He regularly writes for the San Francisco Examiner with his column ‘Notorious Crooks’ and he is the Director of Crooks Tours of San Francisco offering walking tours of the city and its criminal history. Paul has appeared in a number of documentaries for the Discovery ID network and on Paramount TV where he featured as an expert on the Zodiac Killer.

Read Paul Drexler’s fascinating true crime book ‘Notorious San Francisco: True Tales Of Crime, Passion, and Murder’ a fast-paced collection of largely untold true crime tales uncovering the dark secrets of San Francisco’s past. Read Crime Traveller’s review here.

“Easy to read in a free-flowing narrative, Drexler’s years of research and writing on San Francisco’s crime history shines through. His skill is telling these historic stories in a way that brings them to life with each and every one being as juicy, lively and engaging as the next with twists and turns fit for any modern day documentary.”

Recommended Books

- Familicidal Hearts: The Emotional Styles of 211 Killers: Neil Websdale uncovers the stories behind 196 male and 15 female perpetrators of familicide exploring the roles of shame, rage, and fear in the lives and crimes of the killers.

- Behind Closed Doors: Violence in the American Family: Based on a seven-year study of over 2,000 families, the authors provide landmark insights into this phenomenon of violence and what causes Americans to inflict it on their family members.

- Parents Who Kill Their Children: Shocking true stories of the world’s most evil parents in Parents Who Kill by Carol Anne Davis, tragic cases of parents who have killed their own children. [Read Review]