By True Crime Historian Paul Drexler

I don’t care what Jiminy Cricket sings in “When You Wish Upon a Star.” Fate is not kind. Just ask David Lamson.

Lamson and his wife Allene were Stanford’s golden couple in the 1920s. David, who had been student body president at Palo Alto High School, was a leading writer and editor on campus. After graduation, he became the sales manager for Stanford University Press. Allene had been women’s editor of The Stanford Daily and had received a master’s degree in journalism from Stanford.

They had a house on the Stanford campus, a beautiful 2-year-old girl and by all accounts a happy marriage.

On Memorial Day 1933, with their maid on vacation and their daughter at her grandmother’s, the couple had the house to themselves. It was 9:00 a.m. on a hot morning and David was working in his backyard garden. He had taken off his shirt and was chatting casually with a neighbor while stoking a bonfire of leaves and yard waste.

At 10 a.m., Julia Place, a local realtor, came by with a client to look at David’s house, which the Lamsons were preparing to rent out for the summer. David told her that he needed to check with his wife first to make sure she was out of the bath. Place and her client waited outside the front door. A few minutes later they heard a strange cry from inside the house. David opened the front door wearing a shirt covered in blood. “My wife has been murdered!” he cried.

What followed was a criminologist’s worst nightmare. Mrs. Buford Brown, the first neighbor to arrive, found David “kneeling on the bathroom floor, his wife’s head in his arms, sobbing hysterically. I induced him to leave to go into the other room. He staggered and then fell to the floor in a faint.” She started cleaning up the blood in the bathroom.

By the time police arrived, a half dozen neighbors and friends had been in and out of the tiny 70-square-foot bathroom, moving evidence and tracking blood over the house. It was like a horrifying version of the stateroom scene from the Marx Brothers’ Night at the Opera. Palo Alto police officers arrived to find Allene’s naked body draped facedown over the edge of a bathtub full of water. There was one large and two small wounds on the back of her head. The sheriff arrived and quickly decided it was murder.

The sheriff interrogated David Lamson, whom he felt was the only person with the means and opportunity to commit the murder. Lamson, who was still in a state of shock, was fuzzy on the details of his day’s activities, which made the sheriff even more suspicious. Police found a foot-long metal pipe at the bottom of the bonfire David had been stoking. Preliminary tests said there was blood on the pipe. They also found what were thought to be bloodstains on the back porch, but none on the front porch — through which any intruder would have had to exit. Lamson, the only person with the means and opportunity, was obviously guilty. All they needed was a motive.

The press was only too happy to oblige. The Lamson case had all the ingredients to make a city editor drool like a Pavlovian dog: A young beautiful victim, a mysterious death, an unlikely suspect, all in the pastoral setting of Stanford University. All it needed was a little spice. “Cherchez la femme!” the newspapers declared.

It was rumored that David had impregnated Doris Roberts, the Lamsons’ beautiful maid. This rumor dissolved when her baby’s hair matched that of her red-headed fiancé.

“Find another woman!” said the newspapers. And they did. She was Sara Kelley, “the blonde divorcée from Sacramento.” David and Sara had known each other at Stanford 10 years earlier and he had run into her recently at the “Sacramento Union,” where she worked. The district attorney found witnesses who saw them having dinner together, but always as part of a larger group. Police found love poems Kelley had written in Lamson’s office drawer, but they were poems that had been written for publication.

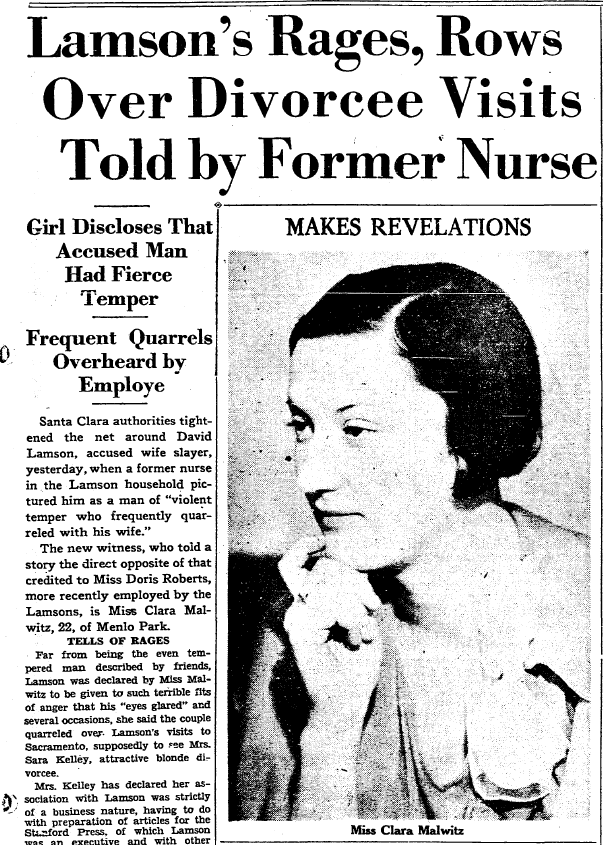

Doris Roberts, their maid, described the Lamsons’ relationship as warm and loving, and an examination of Allene’s diary revealed no trace of conflict. Clara Malwitz, the substitute maid, had a different story. “It is time somebody told the truth,” said Clara. “It is plain to be seen that someone has Dora Roberts frightened.” Malwitz claimed that David had a bad temper and that Allene was afraid of him. Clara also confirmed reports that Mrs. Lamson was in poor health.

The district attorney and sheriff tried the case in the press, painting Lamson as a devious person and stating medical testimony that an accidental death was physically impossible. To buttress their case the prosecution hired the foremost criminologist of the day, Dr. E.O. Heinrich.

The defense made a tactical error by sequestering Doris Roberts and Sara Kelley, who hated the harsh public spotlight, but who could counteract the prosecution’s attacks on David’s character. This left the narrative with Clara, who loved being the center of attention.

Still, there were questions. If David Lamson had killed his wife before 9 a.m., how could he have been so relaxed talking to his neighbors just a few minutes later?

As the case moved toward the trial, a startling development occurred. Dr. E.O. Heinrich, after examining the death scene, concluded that Allene’s death was an accident and joined the defense team.

In early September, the trial began.

According to the prosecution, David’s motive for the murder was sex. They claimed that he was having an affair with a blonde divorcee and that he was sexually frustrated within his marriage.

Witnesses testified that Allene’s health was delicate and that she was often ill. According to David, Allene had a stomach ache the night before she died, so he slept in another room. The prosecution claimed that the Lamsons slept apart because of marital problems and that David was angry about the situation.

The prosecution’s theory was that David confronted Allene in the bathroom the next morning and attacked her with a nine-inch piece of metal pipe. After the murder, the prosecution claimed, he went outside to the garden, raked leaves, chatted with neighbors, and put the murder weapon in the trash fire.

The prosecution explained that David’s calmness before and his grief after Allene’s body was discovered could be explained by the acting training he had learned in his high school and college shows.

The key battle at the trial was fought between prosecution and defense experts over whether the death was murder or an accident.

Dr. A.W. Meyer, head of Stanford Medical School’s anatomy department, testified for the prosecution that the wounds on the back of Allene’s head could have been made only by four separate blows. Other prosecution witnesses testified that Allene’s death could only be murder.

Dr E.O. Heinrich, a famous criminologist, was the key defense expert. The prosecution originally hired Heinrich, but his research convinced him that Lamson was innocent. Heinrich rebutted the prosecution’s claims of blood on the pipe but he was prevented from testifying that Allene’s death was caused by an accidental fall in the bathtub.

The judge ruled this evidence was based on experiments that were not scientifically valid.

Prosecutor A.P. Lindsay ruthlessly appealed to the jury’s emotions. At the time, Santa Clara was an agricultural area — “the prune capital of the world.” Lindsay stirred up the class conflicts between the rural jury and the Stanford University educated defendant. He made sure that large photos of Allene’s bloody body were prominently displayed. He pounded the metal pipe on the jury box during his summation and read the scene from “Oliver Twist,” in which the vicious Bill Sykes beats his girlfriend to death.

At the end of the three-week trial and eight hours of deliberation, the jury found Lamson guilty of first-degree murder and he was sentenced to death. The verdict shocked the academic and legal communities.

August Vollmer, a former Berkeley police chief and University of California criminologist called it, “the most amazing situation that has ever arisen in American jurisprudence — a man condemned to die for something that has never happened, and every bit of circumstantial evidence pointing to his innocence.”

Defense attorney Edwin McKenzie wrote a pro bono, 622-page appellate brief challenging every aspect of the prosecution’s case.

Lamson was sent to San Quentin’s death row and started writing about his experiences. His writing was serialized in the San Francisco Chronicle and later became “We Who Are About to Die,” an extraordinary book, written without anger or self-pity, filled with compassion for both convicts and guards.

“My effort has been to observe and report — to tell you what San Quentin and death row are like, rather than to tell you what happened to me,” Lamson wrote.

In November 1934, the California Supreme Court unanimously overturned the verdict, ruled that the trial judge unfairly kept Dr. Heinrich from testifying, and said the prosecution’s case was weak. At the same time, the chief justice commented that Lamson was probably guilty but that the prosecution had not proved it beyond a reasonable doubt.

The second trial lasted three months, and the jury deliberated for 30 hours before it announced that they were deadlocked: nine for conviction and three for acquittal. The District Attorney tried Lamson a third time with identical results.

By this time, Lamson’s book had become a best-seller and public opinion had shifted in his favor. After the fourth trial ended in a mistrial, the prosecutor gave up and dismissed the charges.

David Lamson was reunited with his daughter Jenny, who he had not seen for three years. Within a few weeks, they moved to Hollywood, where he worked on the screenplay for the movie version of “We Who Are About to Die.

In 1937, Lamson wrote “Whirlpool,” a novel based on his case, which also became a best-seller. He met and married film and magazine writer Ruth Rankin, who became Jenny’s stepmother. Over the next 15 years, he wrote more than 80 stories for the Saturday Evening Post and other popular magazines.

He died in Los Altos in 1975 at the age of 72.

About the Author: Paul Drexler is a writer and crime historian in San Francisco. He regularly writes for the San Francisco Examiner with his column ‘Notorious Crooks’ and he is the Director of Crooks Tours of San Francisco offering walking tours of the city and its criminal history. Paul has appeared in a number of documentaries for the Discovery ID network and on Paramount TV where he featured as an expert on the Zodiac Killer.

Read Paul Drexler’s fascinating true crime book ‘Notorious San Francisco: True Tales Of Crime, Passion, and Murder’ a fast-paced collection of largely untold true crime tales uncovering the dark secrets of San Francisco’s past. Read Crime Traveller’s review here.

“Easy to read in a free-flowing narrative, Drexler’s years of research and writing on San Francisco’s crime history shines through. His skill is telling these historic stories in a way that brings them to life with each and every one being as juicy, lively and engaging as the next with twists and turns fit for any modern day documentary.”