The second installment in our Murder To Movies series by San Francisco true-crime historian and writer Paul Drexler.

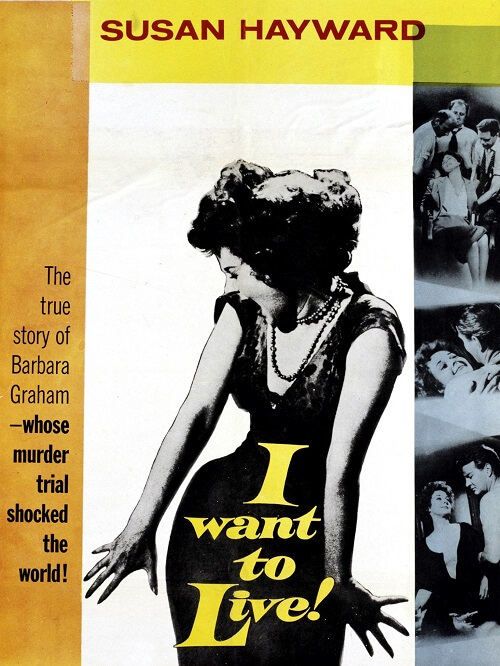

“Take deep breaths, it’s easier,” says the prison guard to Barbara Graham, as she is strapped into the gas chamber. “How would you know? “ she replies bitterly. This is the final scene in “I Want to Live,” the movie which won Susan Hayward, playing Barbara Graham, an Academy Award. The truth of this movie has been questioned, but the presentation of Barbara’s final days in San Quentin is disturbingly accurate.

Barbara died only a few miles from Oakland, her birthplace, where she was born in 1923. What a short sad trip her life had been. Barbara’s mother, Hortense Wood, was a 15-year-old prostitute, who viewed her daughter as an annoying burden.

When Barbara was two years old, Hortense was sent to The Ventura School for Girls, a reformatory in Southern California. Barbara was shuttled around to an assortment of indifferent caretakers until her mother returned.

Barbara started acting out as a teenager and was also sent to her mother’s alma mater, the Ventura School. Released in 1939 she married a US Coast Guardsman, went to business school, and had her first two children. The marriage did not work out and her husband got custody of their children. Barbara was jailed in San Diego for “lewd and disorderly conduct” in 1942 and for prostitution in 1944.

She worked briefly for legendary madam Sally Stanford in 1945, but Barbara soon drifted into drug use and lured men into crooked gambling games. In 1950, Mark Monroe and Thomas Sitler two ex-San Quentin thugs crashed into Sally Stanford’s bedroom and pistol-whipped Sally demanding money. Sally broke free, ran to the window, and started screaming. The robbers ran out and were soon arrested. Though Barbara barely knew Monroe she agreed to give him an alibi. Her testimony was easily debunked and the men were convicted of robbery. Barbara was convicted of perjury and served a year in jail.

Whatever desire Barbara had to reform ended when her mother Hortense revealed her criminal background and told Barbara’s parole officer she was an unfit mother.

In 1953 she married for the fourth time and had a child with Henry Graham, a drug-addicted bartender with shady friends.

Bad taste in men has been the downfall of many women, but rarely has anyone chosen as poorly as Barbara. Henry’s friends, Jack Santos and Emmet Perkins were vicious killers, without a shred of remorse or compassion. Barbara moved in with Emmet Perkins after leaving her husband and lured men into his gambling games. Through the prison grapevine, Perkins and Santos heard about Mrs. Mabel Monahan, a wealthy woman who had been the mother-in-law of a Las Vegas gambler. It was rumored that she kept $100,000 of his money in a safe in her house.

Mabel Monahan, however, was no naïve, trusting old lady. She was an ex-vaudevillian, had lived in Las Vegas, and was friendly with a number of gamblers. There was no way she would open her door to a strange man. That’s the only reason Barbara was brought along on this score. Her job was to trick Mabel into opening her front door. John True and Baxter Shorter, two safecrackers, were added to the team.

The robbery was a total disaster. There was no safe in the house. The robbers brutally beat Mrs. Monahan, taped a pillowcase over her head, and put her in the closet. Baxter Shorter did not participate in the murder and tried to stop Mrs. Monahan from being beaten. Although the thieves ransacked the house, they missed a purse containing jewelry and $400 in one of the closets and left empty-handed. Mrs. Monahan died of asphyxiation and was discovered two days later.

Shortly after, Baxter was questioned as part of the murder investigation. In order to escape a possible murder rap, Baxter told police of the crime and agreed to testify against the others. Unfortunately for Baxter, someone leaked his testimony to Santo and Perkins who killed him and buried him somewhere in the San Jacinto Mountains.

Police located and arrested Santo, Perkins, Graham, and True.

In exchange for immunity, John True, who had no criminal record, agreed to testify against his co-defendants.

Although Barbara was the least important person in the crime, she became the most important attraction at the trial. A “YAWK” (young attractive woman killer) is God’s gift to Newspapers.

The trial judge was Charles Fricke, known as a “hanging judge. Fricke who sent more people to California’s gas chamber than any judge in California history was a prosecutor’s dream.

Murder cases verdicts often depend on whose story the jury likes best. When it came to telling her story, Barbara Graham was her own worst enemy. Instead of dressing modestly, emphasizing her role as a mother, and acting meek, Barbara dressed in tight clothes, talked tough, and sat at the defense table smoking and glaring at the prosecution. She had completely internalized the criminal code. She could easily have gotten a reduced sentence if she had agreed to testify against Santo and Perkins, but it never occurred to her to inform on her companions.

John True’s testimony was the most damaging to Barbara. He testified that it was Barbara, not Perkins who beat Mabel Monahan on the head with a pistol. The press started calling her “Bloody Babs” and the name stuck.

Beneath Barbara’s tough exterior was a woman desperate for acceptance and easy to manipulate. In jail, while awaiting trial, she had an affair with Donna Prow, a young woman serving a year for manslaughter. Donna, in exchange for her release, put Barbara in touch with a “fixer,” a man who would give Barbara an alibi for $25,000. The ”fixer” was really an undercover policeman who later testified that Barbara had admitted being with Santo and Perkins on the night of the murder. When the jury learned of Barbara’s affair with Donna, Barbara’s fate was sealed. She had already been involved in sex, drugs, and murder; the unholy trinity of taboos in 1950s America. Now, on top of that, Barbara was a lesbian!

After deliberating for just five hours the jury brought in a verdict of first-degree murder against all three defendants. Without a recommendation for clemency, the automatic sentence was death.

After Barbara’s conviction, Ed Montgomery, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, corresponded with Graham in prison, wrote a series of articles questioning the verdict and led an effort to save her from the death penalty. The effort failed and Barbara was executed on June 4th, 1955. As she was led into the gas chamber, Barbara said, “Good people are always so sure they are right.”

Montgomery’s articles became the basis for “I Want to Live,” a somewhat fictionalized version of Barbara Graham’s case. The movie, which won Susan Hayward an Oscar in 1958, raised doubt about Barbara’s participation in the crime and claims that she was home with her husband and child on the night of the Monahan murder.

Over the years, Barbara Graham’s guilt has been much debated. Was she an innocent victim of the legal system or a cold-blooded murderer? The answer lies somewhere in between. It is likely that Barbara’s role was to get Mabel Monahan to open her front door. But the idea that Barbara played an active role in the murder is highly unlikely.

Graham was a classic “gun moll”. A gun moll’s job description is to be an accessory, an attractive pawn. They carry and hide guns for their men, give them alibis, and provide unqualified support. Graham’s crimes, prostitution, minor con games, perjury, were all nonviolent. She had never before accompanied Santos and Perkins on a hold-up.

Santos and Perkins, on the other hand, had committed at least six murders. They once bludgeoned to death three young children and their father after a robbery.“ Let’s face it,” Santos admitted on death row, “I’ve been a real stinker.”

So why did John True testify that Barbara Graham took an active and violent role in the killing? True was testifying for his life and saving himself was his only concern. His testimony about what happened to Mrs. Monahan was accurate except for his cast of characters. True recast the part of the attacker, played by Perkins in the actual crime, with Barbara Graham. And he cast himself in the role of Baxter Shorter, who tried to protect Monahan’s.

True’s testimony was false but effective. By casting Graham as “Bloody Babs,” True made himself the only relatable person among the robbers. Baxter Shorter, the only person who could contradict him, was dead. Barbara Graham’s defense argument claimed that she wasn’t at the robbery, so she couldn’t tell the truth, and Perkins and Santos were not testifying.

Was Barbara Graham guilty of murder? Legally, anyone who participates in murder is guilty, whether or not they had anything to do with the actual killing. But given the facts,

It is doubtful that a jury would have recommended the death penalty.

The release of I Want to Live reignited the battle against capital punishment, along with

Caryl Chessman, who was also sent to the gas chamber by Judge Fricke.

Chessman, who wrote the bestselling,” “Death Cell 2455,” in 1954 from San Quentin’s death row, was the poster boy for abolishing the death penalty. His book, along with Barbara Graham’s execution, made capital punishment a personal crusade for millions. His fight for life was international news until his execution in 1960.

Barbara’s prosecutors made it a practice to blacken Barbara’s name to blunt her emotional appeal. They hid John True’s original confession because it conflicted with his trial testimony and leaked false stories claiming Barbara had confessed her guilt to the warden of San Quentin. So, Barbara, who lived as a pawn to criminals, became a pawn in death for both sides in the capital punishment battle. And, as any chess player knows, pawns are easily sacrificed.

About the Author: Paul Drexler is a writer and crime historian in San Francisco. He regularly writes for the San Francisco Examiner with his column ‘Notorious Crooks’ and he is the Director of Crooks Tours of San Francisco offering walking tours of the city and its criminal history. Paul has appeared in a number of documentaries for the Discovery ID network and on Paramount TV where he featured as an expert on the Zodiac Killer.

Read the first part in this Murder to Movies series here.

Read Paul Drexler’s fascinating true crime book ‘Notorious San Francisco: True Tales Of Crime, Passion, and Murder’ a fast-paced collection of largely untold true crime tales uncovering the dark secrets of San Francisco’s past. Read Crime Traveller’s review here.

“Easy to read in a free-flowing narrative, Drexler’s years of research and writing on San Francisco’s crime history shines through. His skill is telling these historic stories in a way that brings them to life with each and every one being as juicy, lively and engaging as the next with twists and turns fit for any modern day documentary.”

![An Innocent Man [Part III]: The Trial of Dr Jeffrey MacDonald – A Critique of the Case](https://www.crimetraveller.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Jeffrey-Macdonald2-324x235.jpg)