On December 14, 2019, 50-year-old Matthew Gibbard from Northamptonshire in England was murdered outside the front doors of a Buenos Aires hotel, as he arrived to check in with his family. True Crime writer and historian Frank Beyer visited the crime scene in Puerto Madero and uncovered the background of the Roba Turistas gang responsible for Matthew Gibbard’s murder.

Modus Operandi

In the international arrivals hall at Ezeiza Airport the spotter for the gang waits. He has sharp eyes and must be decisive. When a flight comes in from Europe or North America he pays special attention. Those wearing luxury watches beware, brand-name luggage is another indicator that the arriving passenger might be loaded with goodies.

As not to raise suspicion the spotter holds a sign with a made up name on it and so he passes for a waiting driver. When he chooses a target, the rest of the gang is alerted and the recent arrival’s ride is followed into the city.

The roba turistas gang flew somewhat under the radar until December 14, 2019 when an armed robbery went wrong and they made the foreign press. The gang was made up of Venezuelans and Argentinians. I’d heard of Peruvians, Bolivians, Paraguayans, Chinese and Colombians being involved in organised crime in Argentina – this was the first high profile case involving Venezuelans.

On November 19th, 2019 a Canadian man was attacked at the entrance of the Intercontinental Hotel in downtown Buenos Aires. Two men with guns beat him and then kicked him after he fell down. They took a Louis Vuitton bag containing a laptop but failed to get anything out of his pockets before riding off on the back of motorbikes. This happened in broad daylight. Shaken, the Canadian reported the crime to police, however, it would take more than this incident for the police to kick into action and take the gang down.

Thirteen days later the gang didn’t wait for their victim to reach his hotel. They assaulted the president of Hapag Lloyd America on 25 de Mayo motorway. Hapag Lloyd is the fifth largest shipping company in the world. The victim, a Dane, was wearing a Patek Phillipe watch worth 100,000 dollars. The motorbike riding robbers were supported by two men in a grey Peurgeot. They got away with the watch, two notebooks, 400 hundred dollars, 300 Euros and 500 Danish crowns. There is a history of stolen luxury watches being sold on Facebook in Argentina. Having a one-hundred-thousand-dollar watch on your wrist seems stupid when turning up in a country with a significant crime rate. I wondered at the spotter’s ability to pick out expensive watches – I suppose there is a lot of knowledge about that sort of thing in criminal groups.

On the 6th of December roba turistas struck again when a gunman entered a hotel in the upmarket neighbourhood of Recoleta. Inside an English family was checking in, behind them a Greek man was waiting his turn to register. The gunman grabbed the Greek’s wrist and wrestled with him, managing to take off the watch. This was caught on video as was another incident in Recoleta in which the target was an Argentine man who’d flown in from the United States. An assailant followed the victim, Alejandro, into the building that he lived in. Alejandro had three suitcases to get through the front security door, so there was plenty of time for the criminal to enter. He pointed his gun and took Alejandro’s watch but ignored the suitcases. Alejandro waited several seconds and then went outside to alert the police. However, the gunman was still out there and again pointed his weapon before making off on a motorcycle. Alejandro said there were always police on the corner, the area was crawling with police – but video cameras and police presence wasn’t stopping the gang. Alejandro recognised the gunman as Venezuelan from his accent and he also claimed the Venezuelans in the gang were the hitmen, sicarios, who would kill at the drop of a hat. They were contracted by the Argentines who took care of the logistics.

Similar attacks in early December were also attributed to the gang. In one incident, assailants were attempting to rob an English couple when a courageous member of the public crashed their car into a motorbike thus thwarting the robbery. Residents of the area delivered one of the robbers to the police. This first member of the gang to fall was twenty-nine-year-old Venezuelan citizen, Miguel Ángel Aguirre. In the attempted robbery he and an accomplice were after the Englishman’s rolex – again demonstrating the folly of arriving in the city wearing a nice watch.

An Influx With Advantages

Opinion is split in Argentina on whether Nicolas Maduro, the President of Venezuela, is an evil dictator or a legitimate leader victimised by Yankee imperialism. Whatever the case, Venezuela has a humanitarian crisis and huge waves of its citizens are leaving. Argentina is fifth place in terms of numbers arriving. In 2015 around 6000 Venezuelans entered Argentina. In 2018 thanks largely to the Argentine government making requirements for residency more flexible, 70,000 arrived, in 2019 the number doubled.

A study on Venezuelan immigrants in Argentina showed them to be well qualified. They found work quickly while locals often struggled and this opened the debate on what was wrong with Argentine work culture. Some suggest the problem is immigrants from the bordering countries: Peru, Bolivia and Paraguay, who come to take advantage of free healthcare and receive social welfare plans from leftwing governments looking for votes. Children never see their parents work and are then trapped in the same cycle. Others blame the arrogant ‘middle’ Argentina, especially in Buenos Aires, those who think they are too good for the jobs they have. A friend compared them to the children of rich parents who squandor the fortune, but Argentina has not been rich since the 1940s.

Another friend, ‘Ramiro’, works for Boca, the famous Argentine football club. He told me that one of the managers at Boca owns a restaurant in the upscale neighbourhood Recoleta and he only hires Venezuelan waitresses. This is because they treat people well and when there are no customers they find work to do – cleaning or organising cutlery. Argentine waitresses, according to Ramiro, have a bad attitude and provide snail-like service. Worse still when you fire them they file a case against you. In Argentina, it’s quite common to sue for wrongful dismissal and win. I’ve been fired in Argentina, I didn’t even have a visa and my employer paid me out an extra month to placate me. Many bars and restaurants in Buenos Aires now hire Venezuelans, both for the good service they provide and that eternal truth that new immigrants put up with more from their boss than more established groups and locals.

For most of my recent stay in Argentina, I hoped that not only waiters, but also the drivers I came into contact with were Venezuelan. Why? When my Uber driver asked me what music I wanted and whether the aircon was at the right level I thought I’d gone through a space portal. This polite, professional driver was a Venezuelan. Argentine drivers, in contrast, were usually disgruntled and went on long rants about Uber, the government and foreigners. My dealings with medical professionals in Argentina have always been excellent, but it’s worth adding to the picture that there has been an influx of Venezuelan doctors into Argentina and their qualifications are being recognised. The government has a program that sends them to rural areas, thus they cover a great need. The flip side of this is that there is a huge brain-drain from Venezuela. Many educated Venezuelans are not working in their areas of expertise in Argentina, some are, but whatever they do they seem to take pride in their work.

Venezuela has a high crime rate and the criminal element is leaking into neighbouring countries such as Peru, where in January 2020 police raided a hotel in the capital Lima and arrested over one hundred Venezuelans believed to have been involved in organised crime. Argentina has not experienced problems of this magnitude. However, I worried the roba turistas gang would damage the reputation of the Venezuelan community, which, in general, is seen as very hardworking in Argentina. The gang also put the tourism industry at grave risk.

Scene Of The Crime

Down the hill from the bustling centre or microcentro is Puerto Madero, a neighbourhood plucked from another city and added on to this South American metropolis. Buenos Aires is a massive grid city of blocks and plazas with neoclassical, Belle Epoque and other styles of very European architecture. This all goes out the window with Puerto Madero, the old port that has been revitalized from 1990 onwards. The skyscrapers of Puerto Madero wouldn’t be out of place in a development zone on the outskirts of Shanghai. More attractive are the old docks lined with buildings made from Manchester red brick and swanky restaurants. There are plenty of parks and the riverside costanera is full of stalls selling hot dogs and steak sandwiches to people with modest budgets.

From the costanera the view of the muddy Rio de la Plata is blocked by the reserva ecologica, a large expanse of reclaimed land popular with runners. Puerto Madero has a small shanty town, Villa Rodrigo Bueno, but most of the families have been moved to the adjacent housing project. Puerto Madero has some of the most expensive real estate in Buenos Aires and is generally seen as safe because it is under the control of the federal prefectura rather than the city police. The current president, Alberto Fernandez lives there, so did Alberto Nisman, the Argentine prosecutor who died in 2015. The murder or suicide of Alberto Nisman is the biggest criminal case in Argentina this centrury, a six-part documentary dealing with this incredibly complex case was released on Netflix in December 2019. Nisman was in charge of investigating the 1994 bombing of AMIA, a Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires. Eighty-five people lost their lives in this terrorist attack. Nisman was going to denounce then President Cristina Kirchner for covering up Iranian participation in the bombing. However, the night before he was due to make his declaration he was found dead in his flash Puerto Madero apartment.

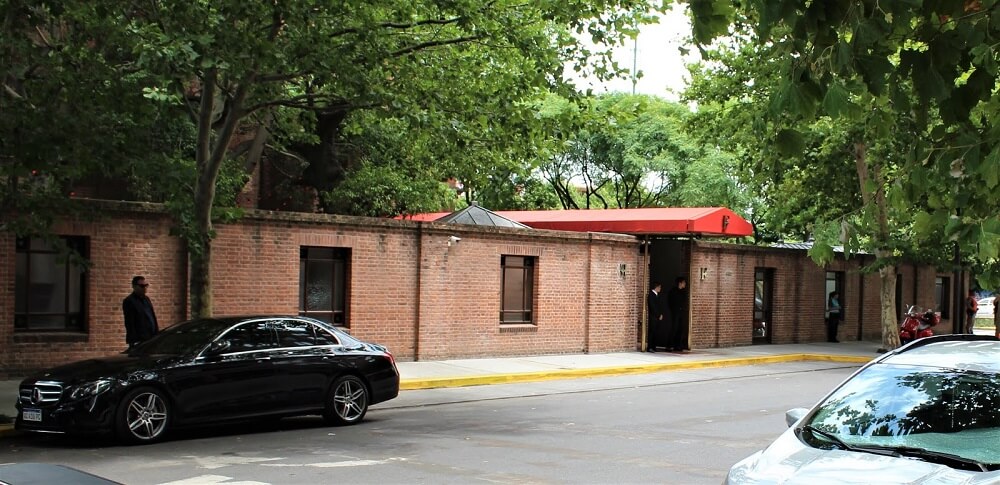

Hotel Faena, 445 Martha Soletti Street, Puerto Madero is an impressive building of red brick. Large trees provide shade on Soletti Street, which is free of the traffic that chokes the city above. A night in Faena costs over 400 USD, about what the average Argentine school teacher makes in a month. The day I went to take a look a prefectura officer was guarding the service entry at the back of the building. Around the front there was a guy in a suit and dark glasses and two more prefectura officers nearby. This heavy security was for show really because the crime had already been committed, an Englishman was shot dead at the hotel entrance the week before.

December 14, 2019

Fifty-year-old Matthew Gibbard lived in a stone mansion – a grade II historical building – in the village of Lowick, Northamptonshire. The population of the village is around three hundred and Matthew was well-known to locals, especially down at the local pub, The Snooty Fox. Matthew was a Ferrari enthusiast and had his own helicopter. The family business, Tingdene, is very successful and Matthew was a director. Tingdene sells prefabricated retirement homes which are delivered to residential park sections. The customer owns the house, which is technically a mobile home, and pays for it to sit on the land. In this way you can get a new home for a reasonable price.

Gibbard travelled widely for his job but was in Buenos Aires for a family holiday. At nine on Saturday morning, he and five family members arrived in Buenos Aires on a British Airways flight. They evidently caught the spotter’s eye as footage shows their white combi van being followed down the motorway by a motorbike and two cars. Security cameras captured the Gibbard family’s arrival at the Faena Hotel, the video is not of great quality and everything happens quickly but the essentials of the crime can be seen.

The video, published in the press, begins with the driver unloading luggage from the back of the van. The first sign of trouble is when staff and guests hurry back inside the hotel entrance. From behind the van, Gibbard’s twenty-eight-year-old son-in-law, Stefan Joshua Zone, appears, he is backing away from a man with a gun wearing a blue hoodie. The driver later reported that he heard yells of “suitcase” and ‘watch”. From another camera we see Matthew Gibbard, in a black t-shirt, running from the scene with a bag in one hand, only to turn and see Zone fighting on the ground with the man in the hoodie. A helmeted motorbike rider, another criminal, gets off his bike to also attack Zone. Matthew runs back and aims a kick at the man wearing the helmet. In all this a woman, a member of Matthew’s family, manages to get away with some of the luggage that has been dropped on the ground. Zone is now on his feet and Matthew tries to run off again but is pursued by the man with the gun. The motorbike rider retreats from Zone and draws a gun himself, Zone puts his hands up. Then both criminals have Matthew on the ground, Zone approaches to help the older man and gets shot in the leg. Matthew gets up again and fights briefly with the rider, who is back on his bike, before getting shot as well. The two gang members make off on the bike, ahead of them is a red Ford Fiat identified by the police as one of the vehicles that had followed the Gibbard family from the airport.

Matthew received the bullet through his right armpit and he later died in hospital. Stefan Joshua Zone survived. During the assault the hotel staff and driver were frozen in shock. There is a suggestion that at one stage in the forty-second long nightmarish attack, one of the assailants pulled the trigger and his pistol just clicked and this emboldened Gibbard to fight back more. But why did Gibbard and Zone resist in the first place? It was probably an instinctive reaction.

Fall Of The Gang

President Alberto Fernandez commented that this was an atrocious crime and could not be tolerated. This message showed the authorities were taking things seriously. Fernandez had taken office less than a week before the killing and some in the conservative press were already calling his new minister of security, Sabina Frederic the minister of ‘insecurity’. Aware of needing to seem tough on violent crime, he said that the full weight of the law must be brought down on the culprits. The Argentine Chamber of Tourism said that these kinds of incidents were putting tourism, Argentina’s fourth biggest earner in the export sector, at risk. In November 2019 the Association of tourist hotels of Argentina had warned that armed robberies in front of and inside hotels were on the rise and not only tourists but staff were being threatened with violence.

In the afternoon of December 14 police raids began in earnest. Vehicles and cash were recovered and arrests were made. Three Argentinians and five Venezuelans were captured by Tuesday. The Argentines were accused of having provided vehicles and logistics. The gunman in the blue hoodie, the twenty-one year old Venezuelan Ángel Eduardo Lozano Azuaje, alias Cachete – a nickname possibly given to him for his baby face chubby cheeks – was caught in Jujuy Province trying to cross over into neighbouring Bolivia. This was the same escape route out of Argentina taken by Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid in the early 1900s. The famous American outlaws were also on the run after having committed armed robbery. Cachete, police believe fired the shot which killed Gibbard using a .380 calibre pistol. Earlier in December he had entered Argentina illegally probably because of his criminal record in Venezuela.

Two other Venezuelans were caught in the northern Salta Province also on their way to Bolivia. Salta and Jujuy are largely semi-arid and mountainous – they are popular with tourists for colourful lunar landscapes and salt flats. Photos of the captured men with blurred faces, kneeling with their hands handcuffed behind their backs appeared in the press. Flanking them in the photos are two national gendarmerie officers in khaki uniforms. The images are crude, conveying the message “look we’ve got the bad guys”. It made me wonder just a little whether these guys really were the culprits – or that the pressure to make arrests had led authorities to arrest any Venezuelans who fit the bill.

In 2019 two out of every ten people detained by police in the city of Buenos Aires were foreigners. This wasn’t the first case of an Argentine criminal group using migrants to do the dirty work. The Venezuelans captured after the murder of Gibbard are all in preventivie custody, however, the Argentinians arrested have been released because of lack of evidence.

About the author: Frank Beyer, from New Zealand, writes about history, true crime and international relations. His articles have appeared in the LA Review of Books, South China Morning Post and History is Now magazine. More of his writing here: https://frankebeyer.contently.com/

Read More on Crime Traveller from Frank Beyer: