Written by Becky Kotnik

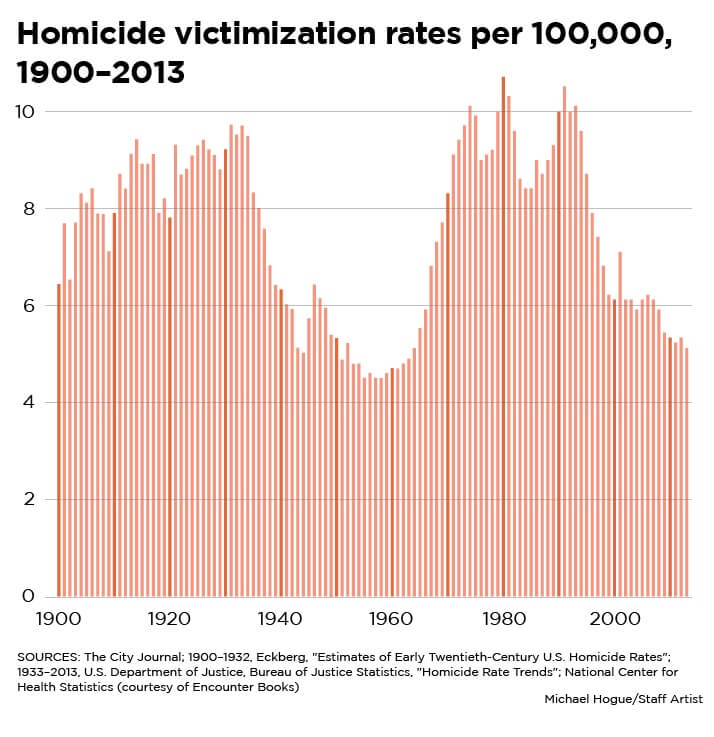

I never would have considered myself a true crime fan. I have not read an Ann Rule book or watched the ID channel. Recently though I have been obsessed with reading about the psychology of criminals and the various True Crime Podcasts that are popular now. After all of this true crime consumption, I noticed that serial killings are on the decline, rising during the 60s, and 70s, and peaking in the 80s. Not being very familiar with crime in general I had no idea why and decided to look into it.

Three theories have been put forth by criminologists which I will explore in this article; First, World War Two left a lasting impact on culture, including the children of returning soldiers; Second, serial killings rise with population booms of young men, particularly those that were unwanted; and finally, the environmental toxicity of lead on these already high-risk individuals lead to violent and deviant acts.

The first theory I will examine is how World War Two may have influenced the swift incline in serial killings. What were the effects the violent war had on the families and children of returning soldiers?

In Jessica Murphy’s 2018 article “Why were there so many serial killers in the 1980s?” for BBC Toronto, the war had a tremendous effect on the families and children of those returning from battle. She states that many serial killers, “were children during World War Two and the ensuing post-war era – a time when the psychological impact of the global conflict and its savagery was not being discussed.”

Data does show that there was an increase although not as dramatic, in murder following World War One from the time period of 1935 to 1959. Unfortunately, for this theory, there is not much concrete evidence to back it up. The closest study is explained in Peter Vronsky’s 2007 book Female Serial Killers: How and Why Women Become Monsters.

“The development of psychopathy is linked to attachment theory advanced by developmental psychologist John Bowlby in the 1950s. After observing the effects on children suddenly separated from their primary caregivers in England during World War II, Bowlby became convinced that when dealing with disturb children psychiatry was overemphasizing their fantasies instead of focusing on children’s real-life experiences.”

Peter Vronsky

The trauma of war’s influence on returning soldiers and society helps explain the rise and fall of serial killers.

Serial killings like other forms of crime do rise with population booms of young men, particularly those that were unwanted. Serial murder has followed the same patterns of other types of violent crime. The population of young men jumped almost 30% in the 1960s and 43% in 1970. Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner’s book Freakonomics put forth this theory brilliantly. They explain unwantedness as:

“The expansive social-sciences literature which showed that children born to parents who didn’t truly want that child, or weren’t ready for that child, these children were more likely to have worse outcomes as they grew up — health and education outcomes. But also, these so-called “unwanted” kids would ultimately be more likely to engage in criminal behaviors.”

Levitt & Dubner

Therefore, with the legalization of abortion, this unwantedness was mitigated. The rate of crime in general decreased significantly including serial killings.

As much as this theory when laid out makes perfect sense, research by Farrell, Tilley, and Tseloi in their paper “Why the Crime Drop?” proposes that only increased security can be proven to affect the crime rate. They analyzed and tested 16 other theories including the legalization of abortion.

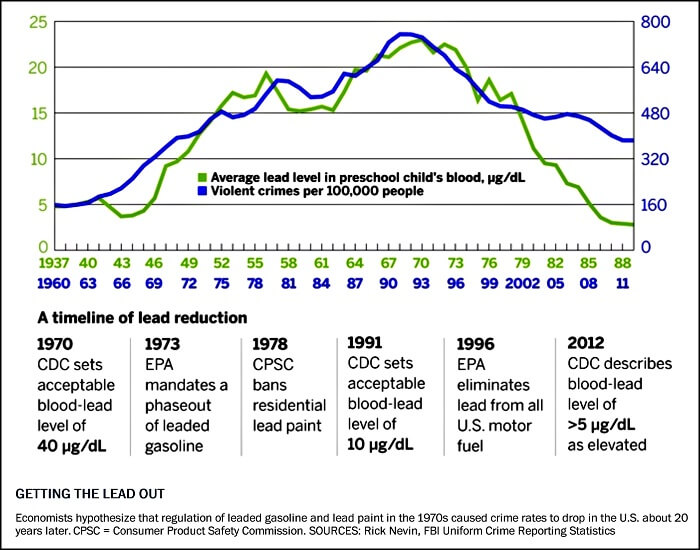

For someone that loves all things scary this next explanation of crime rates scares me so much I almost didn’t want to research it: Lead exposure. Maybe it does not cause serial killers, but it exacerbates the causes above. It puts an already vulnerable population further at risk. The article I found particularly terrifying was Kevin Drum’s 2013 article in Mother Jones ‘Lead: America’s Real Criminal Element: The hidden villain behind violent crime, lower IQs, and even the ADHD epidemic.’ According to Drum, “Violent crime follows the same curve, delayed by 20 years, as lead exposure in the US due to leaded gasoline.”

The good news is that thanks in large part to unleaded gasoline things are looking up. Jessica Reyes’s research in ‘Environmental Policy as Social Policy? The Impact of Childhood Lead Exposure on Crime,’ finds that “the reduction in childhood lead exposure in the late 1970s and early 1980s is responsible for significant declines in violent crime in the 1990s, and may cause further declines into the future.”

Serial killing was nothing new in the 1960-1980s. However, serial killings did rise during the period of 1960-1980 for many reasons, including returning soldiers from World War II raising children in the late 40s and early 50s, population booms and subsequent birth control, and environmental toxins. Society as a whole need to be very cognitive of population trends and high-risk populations, especially young men. Furthermore, environmental toxins may have a much more profound effect on public health than just exposure to lead.

About the author: Becky Kotnik lives in the tundra of Minneapolis with her husband and two children. She is a part-time Financial Controller and a fulltime mom. In her free time, she likes to research, write and puzzle. You can see more on her blog The Aspiring Statistician, or follow her on Medium, Twitter and Instagram.

Sources ->

- Drum, K. (2018, February 1). An updated lead-crime roundup for 2018. Mother Jones.

- Drum, K. (2013, January/February). Lead: America’s real criminal element. Mother Jones.

- Farrell, G., Tilley, N., & Tseloni, A. (2014). Why the crime drop? Crime and Justice, 43(1), 421-490.

- Levitt, S. D., & Dubner, S. J. (2009). Freakonomics: A rogue economist explores the hidden side of everything. Harper Collins USA.

- Murphy, J. (2018, August 31). Why were there so many serial killers in the 1980s? BBC News.

- Reyes, J. W. (2007). Environmental policy as social policy? The impact of childhood lead exposure on crime. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 7(1).

- Vronsky, P. (2007). Female serial killers: How and why women become monsters. Berkley Publishing Group.

Recommended Books

- Journey Into Darkness: The world’s top pioneer and expert on criminal profiling delves further into the criminal mind in a range of chilling cases involving rape, arson, child molestation and murder.

- The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers: Accurate, unglamorized information on hundreds of serial murder cases including the Sniper Killers; the Green River Killer; Harold Shipman and Aileen Wuornos.

- Serial Killers: The Method and Madness of Monsters: Vronsky not only offers sound theories on what makes a serial killer, but also provides concrete suggestions on how to survive an encounter with one.

![Has The Zodiac Finally Been Discovered? [Part 2]](https://www.crimetraveller.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FINAL-Zodiac-Uncovered-PART-2-100x70.jpg)