This article is written by Daisy Richards, from De Montfort University.

The murder of Grace Millane in 2018 seized front pages of media outlets worldwide, with article after article fixated on details of her personal history. These details implied that the sexually violent nature of Millane’s death was somehow a product of her own actions, and this treatment is itself part of a much larger media trend in how violence against women is represented.

From the day that her family reported her missing on December 5 to the discovery of her body on December 9, media outlets reported unremittingly on the circumstances surrounding Millane’s disappearance, in a manner that should no longer be acceptable.

On November 4 2019, the trial began and the man charged with her death entered a “not guilty” plea. The media latched on to the trial, covering the defence’s attempt to form an alternative narrative that could throw doubt on just “what kind of girl” Millane had been.

They argued their client had not intended to kill Millane. Instead, he had simply followed her instructions and it was she who had initiated violent sex, as she was “a fan of 50 Shades of Grey” and had learned from an ex-partner.

From this moment, the media coverage of Millane’s murder trial focused almost exclusively on details of her sexual preferences, previous partners, and alleged proclivity for BDSM.

Headlines broadcasted interviews with Millane’s friends and ex-boyfriends who had been interrogated by the defence. Articles were preoccupied with her “kinky fetishes,” “other sexual partners” and described her as a “naive and trusting girl.”

A Historic Problem

By sensationalising Millane’s murder and directing focus towards her intimate preferences and not her killing, media outlets continue to contribute to and perpetuate societal attitudes of victim blaming.

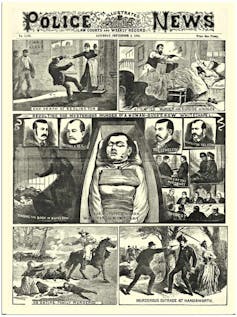

Unfortunately, this kind of journalism isn’t new. It was seen in the coverage of the murder of Mary Nichols, the first victim of Jack the Ripper, more than 100 years ago. Papers included extensive descriptions of Nichols’ injuries – even mentioning that her body was “warm” when discovered – and focused upon her alleged prostitution and alcoholism. It continues to be seen today, as within a 2018 listicle of the most horrific Valentine’s Day crimes, almost all of which featured the murder of a woman by a male partner.

Further Reading:

Jack The Ripper Was Three Killers: New Theory in Sherlock Holmes and the Autumn of Terror

Jack the Ripper Tours London: An Interview with Founder Richard Jones

Journalistic efforts to responsibly cover stories of violence against women have unrelentingly failed. Sadly, profit is and always has been the solitary pursuit of any given news outlet, and cultural appetites for stories featuring details of violence against women are seemingly insatiable.

Representations of Male Victims

It is known that the media’s treatments of female victims of violence differs radically to male counterparts. For instance, research by Marian Meyers in 1996 demonstrated that women are more likely to be infantilised and referred to in articles by their first names (a journalistic practice predominantly reserved for pets and children).

Articles also rarely present violence against women as a systemic societal issue. Instead, the focus is largely episodic, which implies that violence against women occurs within individual situations, instead of as part of women’s everyday lives. Data published in 2018 by the Office for National Statistics found that the majority of victims are female, with about 560,000 female victims and 140,000 male victims in 2017.

As in the case of Millane, there is a tendency within the media to sensationalise and make abstract the bodies of abused, assaulted, and murdered women. These women are dehumanised by reporting that decontextualises them from their day-to-day lives as loving daughters, dedicated students, and loyal friends. This often means that they are remembered through the limited lens that the media places on them after death.

These women, who are physically and metaphorically voiceless, cannot defend themselves, and so myths around women who “ask for it” are subsequently upheld. By focusing on her sexual preferences, and the way in which she “naively” messaged men on fetish dating apps, articles surrounding Millane’s murder framed her as partially responsible for her own brutalisation.

Read more: Domestic abuse bill: proposed changes to protect victims explained

The implicit journalistic messaging throughout the coverage of the trial was that “women should be more careful” as opposed to “men should not murder.” This is evident within headlines surrounding Millane’s murder which prioritise the defence’s argument that she encouraged her killer to apply more force and that her “ex-lover” knew she liked to be choked. This is also seen within the publication of photographs of her in supposedly “revealing” clothing alongside the suitcase her body was buried in.

It is also unmistakeable in the kind of linguistic model used to describe her murder. Instead of cultivating phrases that refer to the actions of the perpetrator who killed Millane, articles repeatedly use passive syntax to describe Millane as having “been killed”. By employing this kind of language, women themselves are consistently framed as inactive victims with no individualisation or agency. Continually, the focus of this kind of media coverage shifts the blame back to the victim, instead of the perpetrator.

Wrongly Immortalised

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of articles concerning violence against women rose from 2,000 to 25,000. As the frequency of this kind of reporting has increased, groups have formed to highlight the injustice and indignity of this kind of coverage.

We Can’t Consent to This is a campaign striving to dispel myths around “the increasing numbers of women and girls killed in violence claimed to be consensual”. While We Level Up focuses on lobbying media for more responsible reporting of domestic abuse cases. Such cases often depict male perpetrators as the “perfect family men” despite their histories of violence and their crimes.

In fact, a 2015 study found that media outlets not only distort depictions of domestic violence cases, foregrounding the most provocative details, but are also more likely to report on female perpetrators of domestic violence. This is despite the fact that two women per week are murdered by male partners in the UK.

As women’s charity Our Watch states: newspapers focus on the method of the murder rather than histories of violence, as if it is “more important for readers to know how but not why men kill their partners”.

Despite arguing that her death was a “sex game gone wrong”, Millane’s murderer was found unanimously guilty on November 22 2019. As Brian Dickey, crown prosecutor for the trial, concluded: “You can’t consent to your own murder.”

These women also cannot consent to the ways in which their intimate histories are manipulated by press coverage. The inclusion of irrelevant details within stories of women who have been murdered by men preserves the idea that these women are not real people. Instead, it paints them as a composite of body parts designed to be ogled, and a series of private decisions designed to be scrutinised.

Women like Millane are wrongly immortalised by news outlets obsessed with sexualising and objectifying their every move even after death, while articles focused on male victims somehow manage to offer the deceased a relative degree of respect. The name of Millane’s killer was surpressed (some outlets have gone on to leak his name) while hers has been tarnished. This is wholly and unashamedly wrong. Millane deserved better, and the media must do better.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.