This is article is by Insight Crime, a part media, part academia and part think tank providing regular reporting, analysis and investigation on the threat to national and citizen security in Latin America and the Caribbean from organized crime. Read the original article here.

In San Pedro Sula’s jailhouse, chaos reigns. The inmates, trapped in their collective misery, battle for control over every inch of their tight quarters. Farm animals and guard dogs roam free and feed off scraps, which can include a human heart. Every day is visitors’ day, and the economy bustles with everything from chicken stands to men who can build customized jail cells. Here you can find a party stocked with champagne and live music. But you can also find an inmate hacked to pieces. Those who guard these quarters are also those who get rich selling air-conditioned rooms, and those who pay the consequences if they get too greedy. That’s how inmates live, on their own virtual island free from government interference, in the San Pedro Sula prison.

The Lawyer’s New World

The lawyer still remembers how he felt when he arrived. The year was 2012, and he was entering a new world. There were new rules and new roles. Time passes differently on the inside, he found out quickly, and banalities, while trivial on the outside, are treasures that one has to pay for and defend at any cost on the inside.

He was in a tough position. The prison is divided by the type of inmate you are and the group with which you are affiliated. The most numerous prisoners — and therefore the most powerful group — are called “paisas.” Paisa is a generic name in Central America for inmates who have no affiliation to a larger, organized criminal group: car thieves, petty drug dealers, and murderers are all paisas. The paisas are the largest bloc, but they are far from being unified. Their power disputes have led to treasonous acts and conspiracies, coup d’etats and wars.

Inside this new world, the lawyer also found infamous predators. The Mara Salvatrucha 13 (MS13) and the Barrio 18, which according to government authorities and the US Treasury Department are two of the largest and most dangerous gangs in the world, were housed on opposite sides of the jail because of their perennial blood-feud.

There were also inmates with mental problems and a group of female prisoners, each of whom have their own section. There were ex-police officers as well; ironically, they were housed next to the MS13. And there were those who had prestige or contacts in high places. They had a separate cell bloc and each prisoner had their own cell, which they refer to as “private rooms.”

The lawyer had been a prosecutor in the Attorney General’s Office. In jail, everything to do with the government is the enemy, so he sought refuge. Luckily, he had contacts and something more important: money. One of his contacts, who was arrested in the same police raid that had snared him and faced similar charges, invited him to live in his “private room.” They shared the space, and lived in the bloc with the other privileged prisoners. They were, quite simply, the prison’s bourgeoisie.

It only took a few days for the lawyer to understand how the system worked.

“The prison administrator told me there were no private rooms. But if I wanted, he would sell me a small piece of the cell bloc, so that I could build my own private space,” he explained to InSight Crime.

So the lawyer negotiated a fee with the prison administrator to build a room. The inmates like to say the cost depends on “how big the frog is,” a local expression referring to the amount of money you look like you have. Payments can reach as high as 200,000 lempiras (roughly $9,000). The lawyer paid 55,000 lempiras (approximately $2,400). The money was registered in a budget item called “non-governmental expenses.” The administrator said this money went towards prison expenses, but nobody believed him.

The lawyer also had to pay for labor and materials. In total, the room cost him 200,000 lempiras, but it came with its perks. He lived in one of the poorest prisons in the world, but he had access to luxuries that even inmates from first-world countries would envy: a television, a microwave and a PlayStation, to name a few. The cell not only provided comfort, but security as well, which the lawyer had quickly come to appreciate.

It was just a few days after his arrival that he had heard the first gun shot. When it started, he was confused. Then he heard another, and he began to grasp what was happening. A full fledged gunfight soon broke out. The lawyer said it sounded like a thunderstorm. The riot that followed lasted several hours, which for the San Pedro Sula prison was short.

The fight itself was a product of the regular in-fighting among the paisas. One paisa group from Cell Bloc 25 was apparently trying to rebel against the then leader of the jail, José Raúl Díaz, alias “Chepe Lora.” The shower of bullets were from Lora’s men, who were putting down the insurgency. The battle left five dead. Prison authorities later asked the boss’ permission to take the bodies away, and everything went back to normal. It was then that the lawyer understood that he didn’t really understand anything about his new world.

The ‘Pesetas’ Era

The San Pedro Sula prison wasn’t always under the paisas’ control. At the end of the 2000s, it was an even more difficult place to understand and to control. Without clear leaders or dominant groups, any shift in power disrupted the entire institution. And a misstep could be taken as an affront. Only one thing was clear: gang members and paisas could not be in the same cell bloc. Mixing them was like preparing a bloodbath.

Prison authorities dealt with this problem by putting the paisas in the largest area of the jail, which could hold up to 1,200 inmates. For a long time, each inmate was responsible for protecting himself. He would have to get his own machete or pistol, or pay someone to get it for him.

But there was a crack in the system, a fissure that no prison official saw: the Honduran gangs are not well organized, and their leaders do not have the same authority over the rank-and-file members as they do in neighboring countries such as El Salvador. There are numerous internal conflicts, and many members desert the gangs altogether. These deserters are known in gang argot as “pesetas,” and they are separated into a separate bloc, away from their former counterparts.

“If you are a peseta, they can’t put you where your [former] gang is [because] they would chop you up immediately, and they can’t put in the other gang’s area because the same thing would happen. The prison isn’t large enough to create another compound, so [the pesetas] have to live with the paisa population,” explained a former peseta prisoner to InSight Crime.

But the pesetas carry the gang in their soul, and they do not stop leading the gang life just because they have abandoned their particular gang. So it was natural that within the prison, pesetas from various gangs united to form their own group. It was a powerful group, probably the most organized of any of those within the paisa sector.

This power increased when they started requesting money from visitors. These requests soon became demands. Once they became aware of their power, they sought more, and soon they began to govern the entire paisa sector at the point of their blades and the ends of their guns.

The prison represents danger, but it also represents opportunity — legal and illegal — from drug sales to contract killings to prostitution. There is even a motel for couples. The pesetas took control of these businesses (and they were careful to provide prison authorities with their share of the profits). Soon, they were also taxing petty drug dealers, alcohol smugglers, and the prisoners who rented out telephones.

One day they would extort an inmate, the next day they would rob someone’s food. To a degree, the abuse was painful but acceptable for the inmates; it was still within the realm of how far a prison gang can push its limits in Central America without provoking revolt. But the pesetas went further. In fact, they committed what many consider the gravest sin of them all when they started targeting visitors.

“It got to the point where the pesetas raped some of the girls that were visiting,” the same peseta ex-prisoner told InSight Crime. Tempers rose, but “no one did anything because [the pesetas] were well organized and controlled the weapons.”

SEE ALSO: Reign of the Kaibil: Guatemala?s Prisons Under Byron Lima

Everything changed in April 2008. The San Pedro Sula prison houses crude men, criminals and those whose reputation precedes them. One of them was Roberto Arturo Contreras, alias “Chele Volqueta,” a bank robber who had escaped prison several times. He had earned his nickname during his most recent escape when he went full speed in a “volqueta,” or dump truck, and slammed it against the prison’s southern wall, creating an enormous hole, all the while firing at prison guards. Several months later, he was captured and sent back to the same prison, where inmates greeted him with a cheer fit for a rock star.

This criminal, like all criminals, had enemies. These enemies could not touch him within the prison, since he had weapons and men. So his enemies paid those who could get to him. At noon on April 26, 2008, while Chele Volqueta was eating stewed chicken in a small prison restaurant, the leader of the pesetas, Jhonny Antonio Jiménez, alias “The Immortal,” shot and killed him. Some say that the Chepe Volqueta choked on his own blood on the floor of Randy’s dining hall, while others claim he choked in the ambulance en route to the hospital. Still others swear that it was a clean kill without much blood. Details always get lost or garbled when recounted by inmates. One thing was clear, though: Immortal had killed San Pedro Sula’s acclaimed bank robber and escape artist in Randy’s dining hall.

A dark cloud fell over the inmates. If they could kill a man of such prestige and power, they could kill anyone. Someone had to act. Three of the oldest and most recognized inmates met with each other; something had to happen or else everyone would be at the mercy of the pesetas.

In stepped a 40-year-old man named Francisco Brevé, a thief with a reputation approaching that of Volqueta. Brevé gathered his men and their weapons, and they responded. One of the attackers, who was 18-years old at the time, said that it wasn’t difficult to put an end to “the plague,” as he referred to the pesetas. Brevé’s men were concentrated in a tight formation with pistols, machetes and grenades, while the pesetas, confident in their power, were scattered across the compound, far from their arsenal.

The massacre was quick. It lasted barely an hour, and left eight dead. But there were a lot of pesetas, and Brevé’s men couldn’t kill all of them. Those who survived were sent to Támara, the prison in Tegucigalpa, where many of them were killed by the friends and admirers of Volqueta.

On that day the pesetas’ blood ran through the San Pedro Sula prison like an irrigation system, giving birth to a new group of “strong men” headed by Francisco Brevé, who from that moment on would be known as Don Brevé.

The Prison Market

A man lifts an enormous brown sack. His wife sees him struggling and decides to help. Between the two of them they drag it little by little down the sidewalk. The heat has already set in, even though it’s only 8:00 a.m. They are, like many others, in line, trying to get into the prison. We huddle next to the wall that still provides a little shade. Those who come later will be at the mercy of the burning sun.

The line moves slowly. The conversation turns equal parts raunchy and utilitarian. A group of older men discuss whether having lots of sex helps people live longer.

“Each time you are with a woman, it takes several seconds off your life,” says an older man. Others interrupt him.

“I would have died years ago,” says a heavy-set man.

“I owe God about ten years,” says another.

There are four of them, but only two are actually here to visit someone in the prison. The rest are waiting to either buy or sell merchandise, including the couple struggling with the large sack. The prison is, quite simply, an enormous market.

Across from us, up against the other side of the wall and protected by a metal roof, is the line for women who are waiting to enter the jail. The first two in line are pregnant. Behind them, several other women are carrying small children who squirm in their arms as the sun blazes above.

The pregnant women and women with children enter the prison first. Behind them are several younger women who are fixing their hair and makeup — beautiful, mixed-race girls, some of whom have dyed their hair blond. Several are wearing such skimpy clothes that there is hardly a need for them to lift their skirts when the female guards check for contraband.

A prisoner walks from the door inside the prison and shouts at the top of his lungs: “Chicken, shampoo, chicken! Don’t lose your place in line, don’t lose your place in line. Chiiiiicken!”

Several people give him money, and he returns shortly with some bags of fried chicken from inside the jail. They give him a tip, and then he goes back through the prison door.

Inside, the inspection is but a mere formality. We give our names, we give our destination, and we go inside. The interrogation lasts no more than a minute. No one asks us what we are doing.

The guard requests our IDs and then hands us each a metal token with a number. “Don’t lose it,” the guard says.

We are with Germán Andino, an artist and journalist, and Daniel Pacheco, an evangelical pastor. The pastor is one of the most well-known activists in the city thanks to his work with gangs in the Rivera Hernández neighborhood, one of the most dangerous in Honduras.

We go past the iron gates and enter the prison. A large group of gang members forms a circle around Pacheco, shaking his hand and saying hello. Most are from Rivera Hernández, and they are happy to see him. They proudly show him the new space they have built within their cell bloc.

They are members of the Barrio 18, the most violent street gang in Honduras. Like the MS13, they are held in special compounds, apart from the paisa population and far away from the rival gangs. A skinny gang member known as “Virus” with five gold chains hanging from his neck is waiting for us.

We had already agreed to meet. He takes us to a large room where at least 30 gang members are watching television or talking with visitors.

We climb a flight of stairs and come to an area where there are five bedrooms. In the last room “El Susurro” is waiting for us. He is lying down like a king and looking up at a flat-screen television mounted on the wall. In his room, there is a mini bar and a pole dancing pole. On his bed are three smartphones. His small refrigerator purrs. He offers us Coca Cola, then, from bed, begins to talk to us.

Competing for the Throne

Don Brevé changed many things in the prison. In a rush to protect himself from potential rivals, he outlawed weapons, from shivs to firearms. Up until then, hiring a hit man was a typical way to discipline a member of your own group or to take revenge on an enemy, like Immortal did to Chele Volqueta. But this new rule made hired killing more difficult within the prison.

Don Brevé also forged a closer relationship with Hugo Hernández, the administrator of the prison. In return, prison authorities legitimized his leadership, giving him the title of “inmate general coordinator.” From that point on, the coordinator has been the intermediary between the administration and the inmates. Complaints, special requests and suggestions are all channeled through him. And the administration communicates its directives to the inmates via the coordinator. This system provides some control. But it is up to the coordinator to impart these orders. And if the coordinator cannot keep the peace, he is of no use to either the administration or the prisoners.

The coordinator also has to keep business flowing. The entire prison economy passes through the hands of the coordinator and the administrator. They hand out the licenses to businesses that operate in the prison corridors — the restaurants, workshops, and small stores. (The main corridor where these businesses operate is called, in a bit of dark jailhouse irony, the “Zone of Death.”) They also give permission for the construction of new rooms and the installation of cable television and other amenities. They provide rooms when visitors come or when prostitutes service clients.

Everything has a quota that must be paid. This quota goes from the business operator to the coordinator to the administrator and, the inmates say, to the warden. To cover up the constant movement of money, they use rubrics like the aforementioned “non-governmental expenses.”

Together, Don Brevé and the prison administrator Hernández worked out ways that allowed the prison population a measure of peace, or at least for those who lived in the paisa sector.

Don Brevé confronted more than one inmate during his time as king of the San Pedro Sula prison. He always won. To cite just one example, Manuel Araújo was a man who had watched everything unfold from the shadows. Perhaps encouraged by the changes, he decided to defy the new king’s orders. He openly carried a weapon, and he armed to the teeth a group of men who had worked with him in the past. Eventually, he and his men took control of part of the paisa compound.

But Araújo’s rebellion did not last long. He was ambushed on the steps of a motel on a day that no one visited him. They shot him from above and from below. Don Brevé’s personal chef and five of Araújo’s gunmen were killed during the brawl. In total, the shootout left nine dead and three injured.

“We killed Manuel because he wanted to take power,” a former inmate told InSight Crime. “He wanted control and began to do the same [things] as those damned pesetas.”

As historians always say, history is written by the victors. And in these stories, Manuel Araújo will always be a tyrant who violated the visitors’ rights and terrified the inmates. Who knows if his rebellion was justified or not. He is dead now, and so is his version of events.

Except for the violent demise of Manuel Araújo, the prisoners who lived through Don Brevé’s period say that peace reigned in the prison. Don Brevé did not have many enemies. And if he did, they preferred to keep their hatred tucked away in the shadow of the cells, so that no one would notice.

But the era of peace was unavoidably coming to an end. Don Brevé was about to finish his sentence. He would be free soon, and blindly promised the inmates that he would continue his good governance from the streets. With the support of Don Brevé and other inmates, one prisoner said he would be Don Brevé’s representative inside the jail. His name was Mario Henríquez, and he promised to be a good leader.

The Barrio 18 Cookout

It’s Sunday, and the line to enter the prison is much longer than on the other days. The sun appears to have noticed the gathering crowd and beats down on us like some sort of capricious god.

After the pantomime search at the entrance and the ritualistic handing over of the metal token, we find ourselves once again inside the Barrio 18 compound. There is music and dozens of children running everywhere. In the kitchen, several gang members and their wives are cooking lunch for everyone.

One of the leaders boasts that, “We aren’t fed by the government. We prepare our own food and buy our own air [conditioners] and our beds.”

It’s true. The Barrio 18 sector is like a refrigerator. It is full of air conditioners and fans. On the second floor, which they have built by hand and with their own materials, they have installed several poker tables and a billiards table with professional cue sticks.

Mandy rests under the table, shaking her ears and sniffing us. She is a nine-month-old pit bull, a breed that is outlawed in Honduras for its supposed violent tendencies. Somehow, though, it’s allowed in this prison.

Lunch hour arrives and all of the visitors are served a plate of fried chicken, french fries, and cabbage salad drenched in sauce. A gang member brings us the plates and buys us a half-liter of Pepsi in the store that they run. This time, the leader El Susurro doesn’t talk to us. He is busy with his own visitors.

In the long line to leave, we meet the visitors from the other sectors. The atmosphere is tense. Those who visited the MS13 look at us with distrust. The women, some of whom are gang members as well, give us an evil look, but no one says anything.

Most of those waiting in line had entered the paisa sector. They carry out armfuls of goods they bought inside.

Suddenly a pickup truck comes barreling through the main gate at full speed, almost crushing us. From the Barrio 18 compound Javier Evelyn Hernández, alias “Flash,” one of the gang’s leaders in San Pedro Sula, appears. A pistol handle can be seen poking from his belt.

Behind him are five other gang members. All of them are wielding home-made grenades disguised as soda cans. These are powerful, artisanal weapons, and some of them are packed with nails. Time seems to stop. Flash and his bodyguards keep an eye on the pickup until it goes into the gang’s compound. Walking back, they get into the truck and close the gate separating them from the other sectors. The soldiers, police and the rest of the visitors breathe a sigh of relief.

The Young King

Unlike Don Brevé’s era, the reign of Mario Henríquez was marred by terror and abuse. Under his rule, in which he too was given the title of “general coordinator,” extortion was the least of the inmates’ problems. Henríquez’s men, for instance, robbed the government-provided food from the poorest inmates, so that they could resell it to the restaurants in the Zone of Death.

“He was growing and growing until it got to the point that we could no longer stand him,” one of Don Brevé’s ex-soldiers told InSight Crime. “He went around saying that he was the only boss of this prison, and really the only boss was Francisco Brevé, although he was free.”

The straw that broke the camel’s back came in February 2012, when the young girlfriend of one of the prisoners known as “Colocho” came to visit. Mario Henríquez’ men called her to their room when she arrived, and Henríquez raped her. The woman left the room sobbing, and then she told Colocho what had happened. Colocho reportedly went crazy. He picked up a grenade, planning to kill Henríquez and the rest of his men, and to take them with him to the next life “all at fucking once!” But Don Brevé’s ex-soldier impeded his path.

“I was also walking with a grenade in my hand, like an Al Qaeda jihadist,” said the former soldier.

Shots were fired, but it wasn’t the moment for a full-on battle. A 26-year-old man calmed Don Brevé’s former troops with promises of bloodshed in the near future, the blood of Mario Henríquez. That man was José Raúl Díaz, better known as “Chepe Lora.” And precisely one month after the first dispute came the coup d’etat.Henríquez’s eyes were shot out, and his head was thrown off the roof of the prison.

“That was a shootout because they were armed, and heavily armed. But we took them by surprise,” one of Don Brevé’s former troops, who would later become a soldier for Chepe Lora, told InSight Crime.

Chepe Lora targeted several cooks who were part of Henríquez’s crew. They later set fire to the kitchen, while the bodies were still inside. Of all the cooks, only one named Roberto, an old prisoner who had spent many years behind bars, survived. But the barbarity of that day left him crazy. Now he wanders the corridors, talking to himself like a ghost.

Henríquez and his gunmen hid inside his cell, one of the luxury cells built at a cost of thousands of dollars. But they met the same fate: fire and lead. They all died. Two inmates then dragged Henríquez’s body from the cell.

“Shrek dragged him out,” a former inmate told InSight Crime, referring to a fellow inmate who went by the name of the famous DreamWorks character. “With a hook, he took off his head and stuck a hen in the hole. They were letting out the anger that had built up towards Mario for having ordered a beating once. Then [another prisoner called] ‘The New David’ cut off his pigeon [penis].”

They say they gave Henríquez’s penis and guts to his own pet dog. They later decapitated the dog. Henríquez’s eyes were shot out, and his head was thrown off the roof of the prison. Thus his rule came to an end, consumed entirely by the prison he once ran.

When the fighting calmed down, the oldest prisoners discussed who the new leader would be. Chepe Lora interrupted. With his young crew at his side, he informed them that he was the new coordinator of the San Pedro Sula prison.

Several inmates we spoke with remember the Chepe Lora era as one of peace and prosperity. Ex-inmates told us of parties with prostitutes, live music and gourmet food. The administrators also remembered it as a time of peace. Chepe Lora surrounded himself with young people. It was a way to break with the old structures.

Chepe Lora was a Robin Hood figure in the neighborhoods of San Pedro Sula as well. Stories circulated of people coming to the prison to ask him for money to buy food and medicine. He even went beyond his dominion of the paisa sector to talk with the Barrio 18 and the MS13. By threatening them with the same fate that befell Mario Henríquez, it is said that he managed to intimidate and subject to his will two of the largest gangs in the world, something many presidents have found impossible.

The journalist José Luis Sanz of the Salvadoran digital news outlet El Faro visited the prison in 2012, while Chepe Lora was still in power. Sanz described him as a reasonable man with a lot of scars. Chepe Lora was missing a finger and had stitches all over his body. Sanz titled his article, “The Just King of Honduras’ Prison from Hell.”

The Third Visit

It’s a weekday, which means the line to get into the jail is much shorter. The guard lowers his head slightly and takes a 50-lempira bill into his hand. This gives you access to the prison without a word, an ID or a signature on an entry list.

We pass through the entrance towards the Zone of Death, the hallway where the restaurants and shops are located. It is difficult to distinguish between visitors and prisoners, and there are no guards inside.

After walking a few meters, we enter through a thick metal door that separates the “private” quarters from the rest of the population. We sit down in the cell of one of these inmates, a former policeman who was interned around the same time as the lawyer. His room has a refrigerator, cable television, a private bathroom and a double bed. On the floor next to the bed, there is a canister of the protein powder Nitro Tech, a jar of fish oil, and a box of Corn Flakes.

There are between 10 and 15 inmates in this section. They are ex police or ex military, as well as some drug traffickers. There is even one member of a wealthy family who was convicted of homicide. The former policeman was captured with hundreds of thousands of dollars on him, but he says the money was loaned to him so he could open a car lot, and insists that he is innocent.

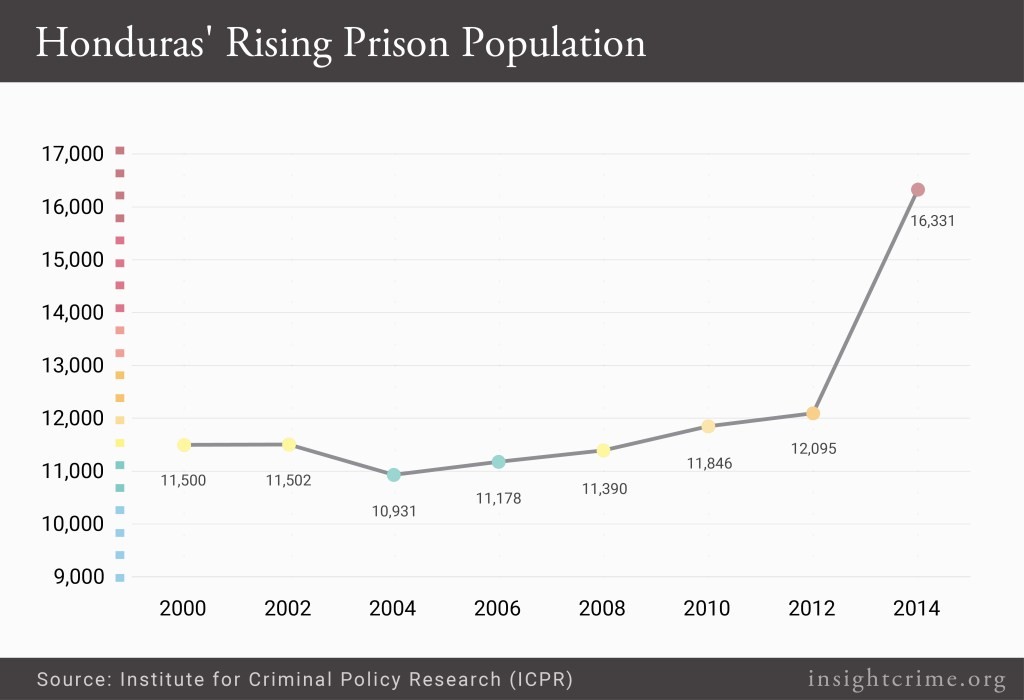

His judicial process is ongoing. More than half of the 17,000 prisoners in Honduras are in the same situation; that is, they are waiting for their trial to end, and a verdict to be announced. At least that way they can plan out their lives.

In the meantime, the former policeman becomes part of the system. The older inhabitants of the “privates” tell us that lineage doesn’t matter. The most important thing is money. You have to pay the prison administrator, in this case Hugo Hernández, however much he asks for.

“And how does Hugo Hernández know how much to charge?” we ask one of the older inmates.

“He does the math,” one of them tells us. “If you have a lot of money, he can charge up to $20,000. If it’s someone who is almost broke, like me, he charges $5,000. But that’s if there is space. If not, they sell you nothing more than a piece of floor, and you have to build and furnish your place. They give you one day, just one, to put in whatever shit you want. Your television, your air conditioner, your kitchen, your bed and anything else you want. After that, if you want to put in something else, it costs more money.”

Not all the money goes to Hugo Hernández. The coordinator also takes a slice, keeping the prison bourgeoisie happy as well. He is also the one who chooses “the most honored and honest” inmates, whom he sends to work in the “private” sector. Each of these elites have under their charge one or several inmates who are essentially their stewards.

“They sent me to buy food in the dining hall, to buy liquor, or beer if he wants to drink,” one of the steward-inmates explained. “In addition, I cleaned his room and made sure nobody robbed anything from him. My boss was a good guy. He gave me some of his food, and sometimes we played FIFA on his PlayStation. But he always beat me.”

Each inmate also pays the coordinator a monthly fee of 500 lempiras for the “administration.” They say that this fee also goes toward the mysterious “non-governmental expenses” line in the budget. These practices have become so institutionalized that they give each person a receipt. (See example below)

Wanting to get the official story, we came back to the prison on a different day. After one hour of waiting in the main office, watching how visitors and large sacks of merchandise entered and exited unchecked, they told us that the director, Colonel Pedro Donoban, was waiting for us. It was a brief meeting. He waived and gesticulated with his enormous arms. He even slapped his desk a few times, and then told us to leave the facility, which we did, accompanied by two soldiers.

We also managed to meet with Hugo Hernández, the administrator, that same day in the Gran Hotel Sula, the largest and most prestigious in San Pedro Sula. He appeared nervous. During our conversation, he was sweating and compulsively eating a large desert. We started the interview diplomatically.

Don Hugo, we understand that there is a certain division among common prisoners and those who pay to have a private space within the facility. Several of these individuals have said that they paid up to $10,000 to have this space.

“That’s a lie,” he answered. “What they pay is a monthly fee of 500 lempiras ($20) to support the prison. I give them a receipt and everything. But nothing else, I don’t charge anything.”

Don Hugo, how does the administration justify the existence of a special place where the inmates can build their own rooms? Testimonies from several people point to unofficial charges that give them access to these privileges.

“Aaaah, it’s not like that. That is a lie…from what I understand, that doesn’t happen.”

What do you mean?

“My understanding is that [that] doesn’t happen.”

Is it possible that the inmates are building their own rooms without you, the administrator, realizing it?

“No, it’s that, look… I… don’t… I don’t know.”

How do you determine who is deserving of a private room and who isn’t?

“Ah… no.. I mean, it [depends on] what there is. If there is [a private room], we give it to them.”

So you just have to ask for it?

“Yes… and if there’s [a room], they give it to them. What happens is that sometimes there are people who have a room, and they rent it out. Because they need to…That’s what they say, since I don’t know very well the rules inside. It’s dangerous to be in there. Inside the gate, those are different rules.”

The Reign of Disorder

When the lawyer and his cellmate entered the facility in 2012, Chepe Lora was the coordinator. They found out that the riot that had occurred that December was an attack on Cell 25, against those who were not following the rules and were attempting to reintroduce killings-for-hire of the type that were common during the days when the pesetas were in charge. Like the majority of the inmates, they were thankful that Chepe Lora was the coordinator for several years.

The lawyer spent just one year in the prison when a judge absolved him of the drug trafficking and money laundering charges. He is now a defense lawyer for many of the same San Pedro Sula inmates, but he doesn’t want to remember anything about his stay there.

“I erased all of that from my life,” he told us. “I don’t want to keep any of the memories that I have.”

For his part, the former policeman is still on the inside with the “private” inmates waiting for his trial to be resolved, for better or for worse. He is known to be prudent, a man who maintains calm in the middle of chaos. The other inmates call him “commander.”The question is if a power vacuum can be resolved by using brick and mortar.

As with Don Brevé before him, Chepe Lora took the prison’s order and security with him when he left the facility. Following several battles for power, the prison is now under the control of a man known as “Chicha,” the name of a particularly strong brew of local hooch. But everything has fallen apart. There have been massacres, riots, thefts and quarrels between prisoners. The administrator, Hugo Hernández, was also sucked into the power struggles, killed in November in a drive-by shooting. The new king, it appears, doesn’t have the same charisma as his predecessor.

The current administration of President Juan Orlando Hernández recognized the futility of maintaining the prison, and in September 2016, said that the San Pedro Sula and Santa Bárbara facilities would be replaced with maximum-security prisons. They have already transferred the first inmates to the new facilities. Among those transferred, hands tied and in uniform for the first time in their lives, were Flash and el Susurro, the Barrio 18 inmates who received us in their prison quarters.

The question is if a power vacuum can be resolved by using brick and mortar. The prison system does not belong to the Honduran state. It belongs to those who prosper on the inside thanks to the lack of government control and those who understand that the disorder inside the jail is their best friend. The chaos legitimizes the system. It almost legalizes it. Without this disorder, a coordinator is no longer a king.

This was a lesson that Chepe Lora learned too late. He was shot down in early July 2014, only a few weeks after he had been freed. Some say that it was his immediate successor who ordered the hit, while others claim it was the MS13 because he had refused to green light the murder of an inmate that sold drugs to the Barrio 18.

What is certain is that his death had to do with this law of the jungle that emanates, silent and potent, from the corridors and cells of the San Pedro Sula jail — where chaos reigns.

*Reporting and writing by Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson and Steven Dudley. The original version of this story was written in Spanish. It was translated by Steven Dudley and edited by David Gagne. Top photo by Rodrigo Abd, Associated Press.

This is article is by Insight Crime. Read the original article on their website here.