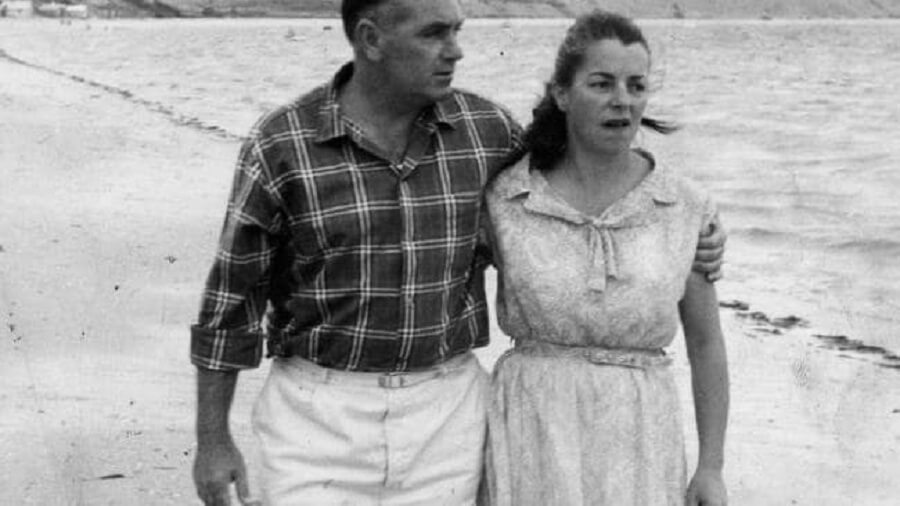

By Australian true crime writer Stephen Karadjis.

When three children vanished from the seaside suburb of Glenelg, in Adelaide, on Australia Day, Wednesday, 26 January 1966, the greatest land, sea, and air search in South Australian history began. Fifty years on, we are no closer to solving the case, and the disappearance of the Beaumont children remains an unfathomable mystery fused eternally with the Australian psyche.

Within days, police dismissed the possibility of misadventure and regarded the matter as one of abduction and homicide. But there has never been a definitive suspect, and the story endures as our most captivating and iconic cold case. The circumstance that led authorities to conclude foul play was involved are witness sightings of a man seen frolicking with the children on the day they went missing. This fact alone, however, could be incidental. Australia in the 1960s was a far more conservative society, and the individual seen, may have been an innocent party, reluctant to go to the police.

There has only ever been one credible suspect, and this man, who came to the attention of police very late in life, is possibly Australia’s most prolific child killer.

The question of whether they did indeed meet with murder or misadventure needs to be revisited.

The Day the Children Vanished

When Adelaide’s householders woke on Wednesday morning, it was already very hot. The mercury in the thermometer was climbing and the temperature was to reach 40 degrees.

A little after 8:30 am, Jane, 9, her sister Arnna, 7, and brother Grant, 4, left their home in Somerton Park and walked along Harding Street to the corner. Nancy Beaumont waited by the front gate and waved to her children as they stepped aboard the bus for the 5-minute ride to Glenelg.

By 2:00 pm Nancy became concerned when they had not come home. She alerted her husband an hour later upon his return from work. Jim and Nancy then began looking for the children, and at 5:00 pm they went to the police.

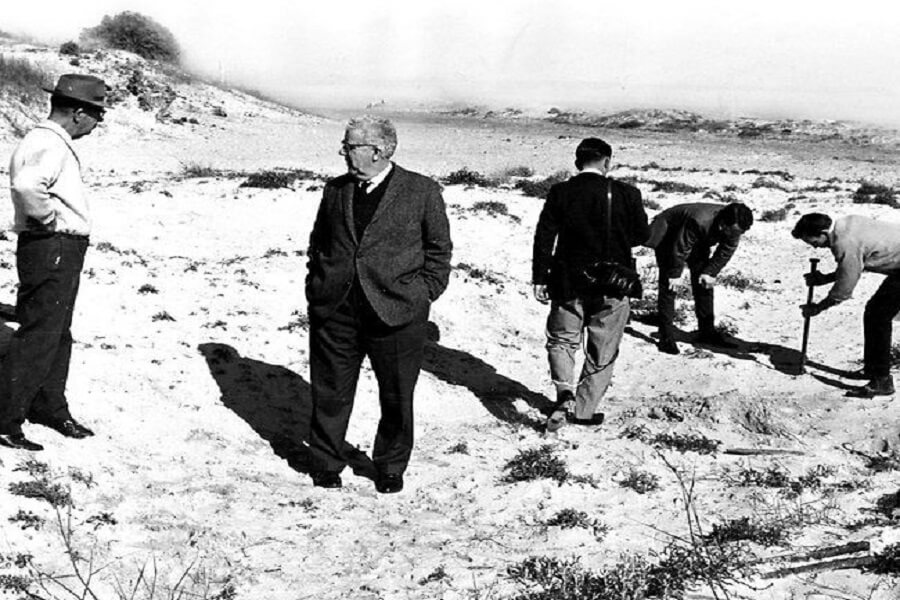

Over the next 36-hours, the largest mobilisation in Australian history for missing persons was mounted. Police, along with the Army, Navy and Airforce and thousands of civilians fanned out in all directions in a desperate search. It was thought the children may have met with an accident, either by drowning or covered over by sand or soil in a landslide or cave-in.

All seaside suburbs and the foreshore were searched to a distance 30-miles south of Adelaide. The sand hills of North Glenelg and in amongst the rocks at the base of the cliff-faces were the scene of a more intensive search. Storm-water drains opening on to beaches were checked, sewage channels explored, and police divers scoured the murky depths of the boat haven. It was drained a week later, as a police-launch kept watch, as the water flowed into the sea.

Neighbourhoods were traversed where land was being subdivided into vacant lots. Some blocks were in the process of excavation and new homes under construction. If the earth looked freshly disturbed, police cadets made diggings, search parties sprouted, and well-meaning citizens made forays on their own. Nothing was ever found.

Police Fear Children Taken

By Friday, 28 January, police began to discount the theory the children had met with an accident. So great was the search, and utility of resources that little hope was now reserved for an outcome other than a tragic one.

On Saturday, 29 January, information was received from a 74-year-old local resident. This woman said she saw a man playing with the children on the lawn of Colley Reserve at the beach between 11:00 am and 11:30 am. The younger girl and little boy were jumping over him as he lay on a towel on the grass, and the older girl was flicking a towel at him. He appeared to be encouraging the children.

She described the man as being in his late 30s, about 6ft 1in tall, slim build with a thin face, light-coloured hair, deeply suntanned, although with a fair complexion and almost certainly Australian. He was wearing navy blue swimming trunks with a white stripe down each side.

On Wednesday, 2 February, a middle-aged woman gave a statement to police. She was sitting on a bench at the beach, alongside an elderly couple, when a man and the 3-children walked up to her. He had asked them. “Have you seen anybody messing around with our clothes? Our money has been pinched.” She said the description given by four other people on the day was accurate. Detectives regarded her account as reliable in corroborating the story given by the 74-year-old woman.

A staff member at Wenzel’s Cake Shop on Jetty Road and who knew the children from previous visits, said she saw them at around 12:30 pm when they purchased a pie and pasties and a couple of other items. She said Jane paid with a one-pound note. Nancy Beaumont, the children’s mother had only given Jane 6 or 8-shillings, enough to cover the cost of lunch and bus fares home. This anomaly led detectives to conclude correctly, that the trio had met someone who gave them the pound note.

Ms Daphne Gregory reported seeing Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont with a man on Australia Day. She said he was in his mid-thirties, with light-brown hair which was neatly parted and brushed. She went on to say that he walked with his arms bowed like an ape. This description was entitled in news articles as, “The Man with the Crazy Walk.”

A local postman, who also knew the children, said he saw them at around 3:00 pm and that they had waved to him and called out, “There’s the postie.” Later, he changed his mind about the time and believed the encounter was in the morning.

The police considered these sightings credible as the stories tended to support the others.

Adelaide’s Dutch Residents Appeal to Clairvoyant

Mr. Gerard Croiset was an internationally renowned psychic who had reputedly assisted The Netherlands police in solving several missing persons cases. Members of Adelaide’s Dutch community had courted him, asking for his assistance and guidance in locating the missing children.

The Dutchman claimed the Adelaide children were dead. He had seen them in a vision after receiving photographs from Australia. They were crawling on hands and knees when all of a sudden the earth tumbles down covering them. The seer said they were lying in an underground cave in the rocks near the beach. He said the cave would be difficult to find because the entrance was sealed off by rocks or sand. The clairvoyant was waiting for a detailed map of the area so he could pinpoint the spot.

On the night of 4 August, two separate rolls of film depicting the beachfront were mailed to the psychic. The first was taken by a cameraman attached to a local television station as he sat in a plane while out at sea. The other had been shot months prior in the early stages of the investigation.

Two Adelaide businessmen agreed to share the cost of flying the psychic to Australia. In early November he arrived in Adelaide to much excitement and anticipation. He flew out of the country days later without success. He said he had been unable to visualise due to the clamouring of news reporters and television crews. “It was strange and unfamiliar. I am upset at my lack of success. I wanted to be of more assistance. It is not an easy thing. It has made me very, very tired.”

During his search, he was shown a warehouse that had recently been erected. The location in Paringa Park was a place the Beaumont children were purported to have played. The clairvoyant said the children were either buried there or had been there at some point. In 1967 holes were drilled into the concrete floor and a partial excavation made and 30-years later a complete demolition of the building. Nothing, however, was found.

The psychic believed the children had met with an accident and that the man seen at the beach had nothing to do with their disappearance.

The Prime Suspect

In 1998, Arthur Stanley Brown, 86, was arrested in Townsville, Queensland and charged with the 26 August 1970 murders of sisters Judith and Susan Mackay, aged 7 and 5. Now in the twilight years of his life, he had never come to the attention of police.

Following a television episode of Crimestoppers documenting the abduction, rape, and murder of the Mackay sisters, a relation of Brown’s wife contacted the show. She reported her suspicions and told of being raped by him as a child. Detectives then interviewed other family members.

Within weeks Brown was arrested and charged with multiple counts of sexual assault and rape, involving his 8-stepchildren and other related minors, aged 3 to 10 years. He was also charged with the murders of the Mackay sisters.

It came to light, that in 1982, Brown’s wife’s relations had sought legal advice after individual family members began to learn from one another that they were not the only one he had molested.

The trial of Arthur Stanley Brown commenced on 18 October 1999 in the Queensland Supreme Court.

Judith and Susan Mackay disappeared from Aitkenvale, Townsville at around 8:10 am while waiting for the school bus. A witness had seen the girls talking to a man who was sitting behind the wheel of a car. Their small bodies were found two days later in the dry bed of Antill Creek, 25 kilometres to the south-west.

At trial, it was revealed that Brown had worked as a carpenter at the Mackay sisters’ school at the time. Testimony was also given of two witness sightings of the girls on the day they went missing.

Jean Twaite was a service station attendant in Ayr, 85 kilometres south of Townsville. She recalled that a blue Vauxhall sedan had pulled in at 11:00 am. The occupant asked for petrol. As she was filling the tank, she noticed the Mackay sisters sitting in the car. She overheard the younger girl ask the man, “Are we there yet?” The older girl then asked, “When are you taking us to mummy? You promised to take us to mummy.”

Neil Lunney had returned from active service in Vietnam. A man in a blue Vauxhall sedan on the road ahead had prevented him from overtaking. His driving had infuriated him. As he attempted to pull alongside, the man turned his head the other way and it appeared he was trying to hide his face. He noticed two girls in the car in Aitkenvale school uniform.

During their encounters, each was observant enough to notice that the driver’s door of the Vauxhall was painted a different colour to the rest of the car. At the time, Arthur Stanley Brown owned a blue Vauxhall sedan with a mismatching coloured driver’s door. The make of the vehicle alone was very uncommon. Both witnesses gave matching descriptions of the driver. They said he had high cheekbones, a narrow skull, and one said he had “Mickey Mouse ears”, all distinguishing features of Brown.

There were, however, several witnesses who reported seeing a car parked on the road adjacent to the murder site. When asked, they thought the make was a Holden. This discrepancy led police at the time to conclude that Twaite and Lunney were in error.

Arthur Stanley Brown made two confessions on separate occasions. The first was to 19-year-old John White in September 1970. The men were drinking in the White Horse Tavern in Charters Towers west of Townsville. White reported the matter to police. They interviewed Brown but he convinced them it was all pub-talk.

The second time was in 1975. John Hill was an apprentice carpenter to Brown. He had mentioned the Mackay sisters. Brown had reacted in an exasperated manner stating, “I know all about that. I did it.” Hill said he did not go to police as Brown’s statement was out of character and he thought he was making it up.

At the conclusion of the trial, the jurors could not agree on a verdict. All evidence relating to the paedophilia charges were not heard in court. Neither was the fact that Brown had molested many of his relations at Antill Creek, where the Mackay sisters were taken. The jury, therefore, had to decide whether the 87-year-old now sitting before them, should be convicted of the rape and murder of two children, relying on decades-old witness testimony.

A retrial stalled after psychiatric assessments showed the defendant was affected cognitively by dementia and Alzheimer’s. The Director of Public Prosecutions had no legal standing to pursue and withdrew all charges.

The widespread media coverage led a woman to contact police. She claimed Brown was the man she had seen as a teenager with Joanne Ratcliffe, 11, and Kirste Gordon, 4. The children were abducted on Saturday, 25 August 1973 from Adelaide Oval, where rivals Norwood and North Adelaide were competing in the final of the Australian Rules Football.

Another witness recalled that Brown had mentioned having seen the Adelaide Festival Centre under construction, and at the stage where it was almost complete. This would place him in Adelaide after June 1973.

It has long been regarded by South Australian police, that the abductor was the same person who took the Beaumont children 7-years earlier. An identikit picture and an artist’s impression both published at the time the two girls were taken, bear a striking likeness to the identikit picture of the alleged kidnapper of the Beaumont children. More importantly, all sketches look identical to Arthur Stanley Brown.

He was employed from 1946 as a maintenance carpenter for the Department of Public Works until his retirement at age 65 in 1977. He had unrestricted access to public buildings and worked unsupervised and his employment records are missing. Police investigations have failed to uncover the dates he took holidays. It has therefore proved impossible to cross-check his whereabouts at the time of the Adelaide Oval abduction in 1973 and on Australia Day 1966.

It needs to be pointed out that homicide detectives and all involved have no doubt Arthur Stanley Brown murdered the Mackay sisters. The Queensland Police Service has closed the case.

So Where are the Beaumont Children?

There were few citizens out there in the 1960s and early 70s responsible for kidnapping, raping and murdering multiple children, from one family unit, on the same day.

Judith and Susan Mackay were taken in 1970, roughly midway in time between the disappearance of Jane, Arnna and Grant Beaumont in 1966, and the abduction of Joanne Ratcliffe and Kirste Gordon in 1973.

If Arthur Stanley Brown took the Beaumont children, as with the Mackay sisters, he most probably drove a similar distance along the highway out of Adelaide, parked the car and led the trio into the scrub. True to form, he likely left them where they lay, neatly folding their clothing and belongings alongside.

The circumstantial evidence stacked against Brown is so high that his guilt is almost beyond doubt. It is also highly probable he is responsible for other unsolved child homicides dating back decades.

Or perhaps the children did indeed meet with an accident, after all, playing hide and seek or deviating as kids do on their way home. Perhaps they were crawling through a crevice of rocks at the beach or a trench of earth on a vacant lot, and the weight of sand or soil fell upon them. Whether people believe in psychics or not, the likelihood of misadventure is a logical explanation for their disappearance. Despite a search on an unprecedented scale, their burial site may have gone unnoticed.

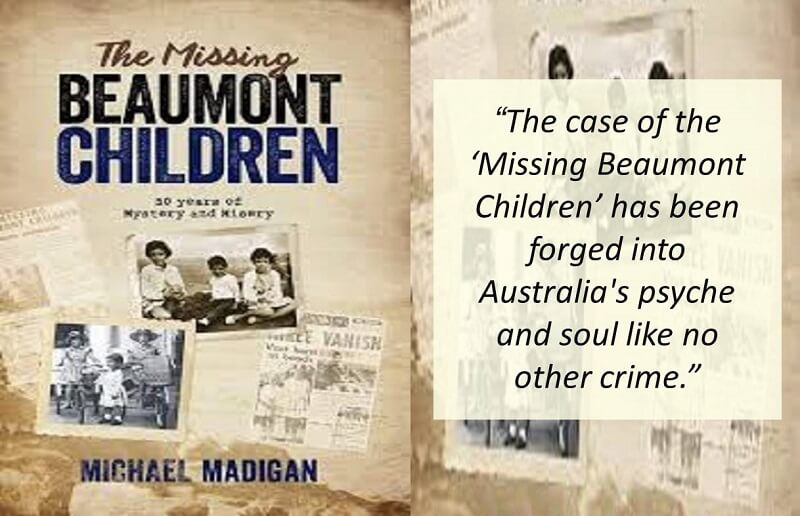

The Missing Beaumont Children: 50 Years Of Mystery

Michael Madigan is an author who has spent time in his research in order to provide a detailed chronological account of those first weeks and months after the Beaumont children went missing.

Today

In the decades since social historians have come to regard this single event, as a turning point in the way parents adjusted their outlook on the issue of child safety.

At the time commentators did not suggest the parents were negligent, or that the children should not have been permitted to go to the beach unescorted. This complacency by the public reflected the attitude of the day.

From then on families were more guarded when it came to their children, thinking twice before allowing them to play unsupervised, keeping a vigil and watching out for strangers. For our nation, it marked the end of innocence.

Epitaph

The mystery behind the fate of the children lingers like a broken record, replaying a verse over and over from a time long ago. It overshadows us like a dark crevasse, a melancholia, a frightening and deeply disturbing nightmare from which we have never woken.

Reference

The information contained in this article was sourced from the original newspaper reports, within the NSW State Library archives and utilising available online resources.

Has the Beauford children’s case ever been solved?