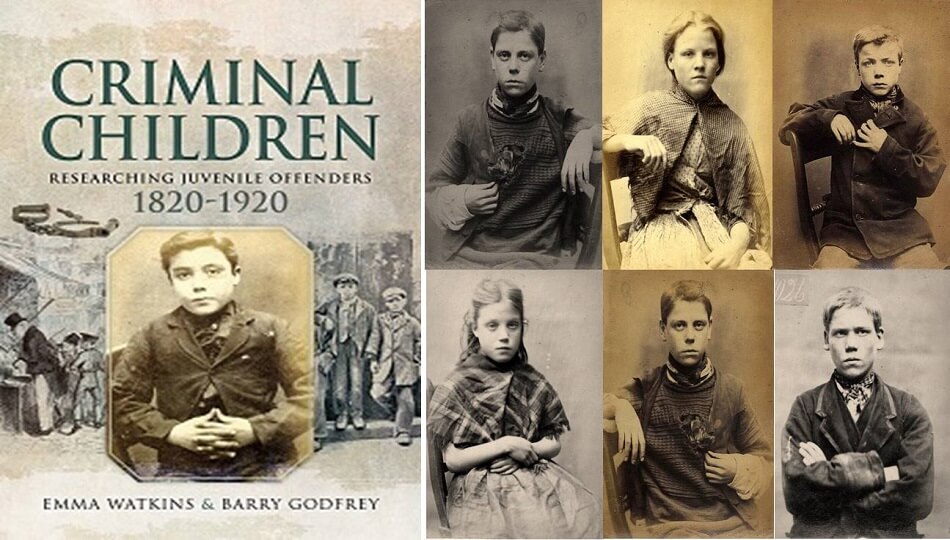

“How were criminal children dealt with in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries? Over this hundred-year period, ideas about the way children should behave – and how they should be corrected when they misbehaved – changed dramatically, and Emma Watkins and Barry Godfrey, in this accessible and expert guide, provide a fascinating introduction to this neglected subject.”

Read the news today and headlines of juvenile crime are prominent and abundant. In many countries concern over children and young adults committing increasingly serious crimes and how to intervene in such a cycle is growing. How does society begin to address the issue of criminal children? There are no easy answers and while our understanding within psychology and neuropsychology on the developing mind and brain of juveniles has aided us greatly, the same concerns and questions remain.

In 2018, Professor Barry

Focusing on 100 years of juvenile offenders across the Victorian period of Britain, it is a fascinating book which takes readers right back to the roots of juvenile delinquency. In the process, this work demonstrates that criminal behavior, disrespect for authority and children deemed ‘out of control’ is most definitely not a new dilemma or a product of 20th century modernism, technology and the online era.

Criminal Children is a well-researched book which highlights how the concept of juvenile delinquency came about in Victorian Britain, the shift in societal attitudes and responses to children who committed

There has been ongoing debate in the UK about the appropriate age of criminal responsibility for children. At what age, society asks, can a child be deemed responsible and culpable for criminal acts?

Currently the law in England and Wales has this age at 10-years-old. In Scotland, the age of criminal responsibility remains at 8-years-old, but a child cannot be prosecuted for a crime unless they are 12 years or older.

In Victorian Britain, this age was set at 7-years-old. Children aged 7 or older were not only deemed responsible for any criminal behavior but they were treated in every way in the same manner as adults; in the criminal justice system and also in employment. Children of this age worked to earn wages to provide for their families. There was no education system in place, no schools to go to and no formal learning structure available.

The industrial revolution in the early 19th century saw factories open and employment opportunities soar. The cities of England and Wales were flooded with individuals from other parts of the world arriving for jobs and moving into local communities. It was a significant period of change which also impacted the children of the era. Parents were now more likely to be in work leaving children free to roam and get up to mischief with little to no supervision outside their own working hours.

Transportation was once such response, more familiar to many of us as punishment for adult criminal behavior, children also found themselves assigned to Australia, almost 10’000 miles away, in response to their crimes. Children as young as 9-years-old were banished to another country for manual labor as punishment for their criminal ways.

During the often long waiting period for a ship to take them across the ocean, children as well as adults were sent to Hulk ships; decommissioned war ships converted to hold prisoners. There were horrid, cramped, disease ridden ships where for many years juveniles were not separated from adults. Children lived on these ships in these conditions along with much older adults who no doubt imparted a great deal of their criminal wisdom and influence upon them.

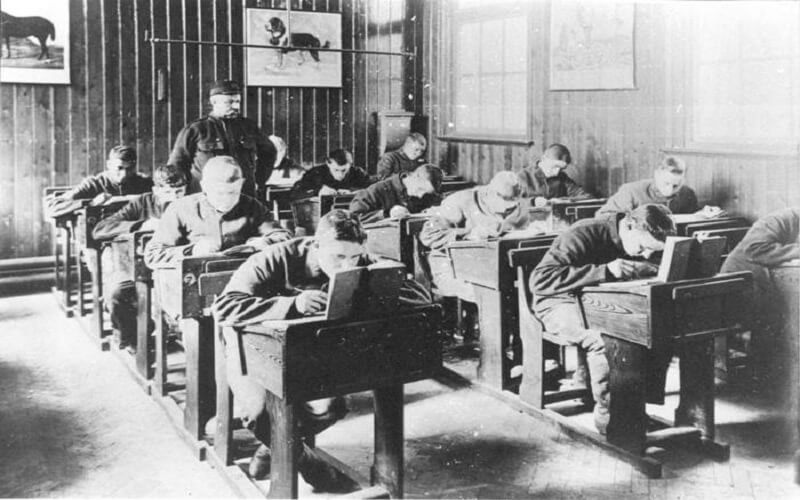

After transportation came the concept of juvenile prisons such as Parkhurst on the Isle of Wight in 1838 and reform schools like the well known Borstal came later in 1900. On the back of a structured education system where children were expected to attend school, these juvenile detention centers imposed strict rules and harsh discipline, designed to enforce youngsters to respect authority and mend their ways.

As the era edged further into the 19th-century attitudes began to shift with a notion that these schools should be a punishment but also provide skills and training to set children on a law-abiding path when they were released.

Children at a Borstal Reform School. Image source: Leeds Beckett University

What is unique about Criminal Children and very much part of its success as a book, is the sense of learning across each chapter with informed guidance on how to carry out research and where to find data and information on the criminal children of the Victorian era. It provides a solid foundation for the reader to continue after finishing the book and enter into their own research should they wish.

The individual case studies included in the final chapter serve to cement this interest, following children from their early beginnings and how their lives were, to their criminal behavior and how the law and society responded. Many are traced after their punishments to see what they did with their lives and the question asked, did they reoffend? Some did not commit another crime that has been recorded as they progressed into their adult lives whereas others returned to a criminal life and found themselves with further punishments and convictions.

A very satisfying read which feels excellent value. While this book focuses on the criminal lives of children and societies attitudes and responses to child crime, it is a wealth of information and well-presented knowledge on the changing historical times across this 100 year period and how this impacted society. It is book historians and those with an interest in British history and the Victorian period especially will enjoy reading.

‘Criminal Children: Researching Juvenile Offenders 1820-1920’ by Emma Watkins and Barry Godfrey is published by Pen & Sword Books and is available at Pen & Sword and at Amazon.