A guest post by San Francisco crime historian Paul Drexler.

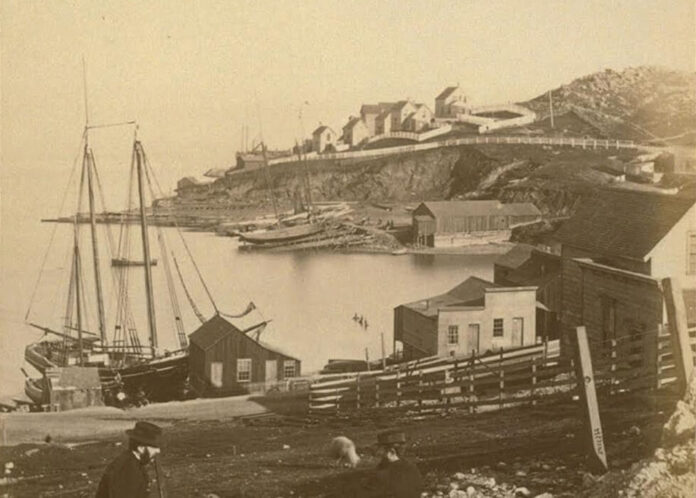

Frank’s kingdom was Irish Hill, a 10-square-block area between 20th and 22nd streets and Illinois Street and Pier 70 in Potrero Hill. Irish Hill was aptly named, with the vast majority of its inhabitants born in the emerald isle. Six feet tall and 230 pounds, Frank earned his crown by becoming the master of politics, drinking and fighting — three of the major Irish arts. In those days, drinking and fighting were both a pastime and an entertainment.

On Saturdays, instead of going to a music hall, the patrons of one saloon would fight the patrons of a different saloon in a roped off area. After the fights, the victors would buy the losers a nickel beer in their saloon.

As the owner of the Union Boarding House, which included a saloon, Frank provided beds, drinks and jobs for hundreds of workers at the Union Iron Works and Pacific Rolling Mills. In exchange, they gave him their fealty and votes.

Frank was often accompanied by an entourage of 10 to 20 brawlers, ready to do his bidding. With the ability to deliver up to 1,000 votes, Frank became a major power broker in the Republican Party.

He soon brought his family over from Ireland to help him rule his kingdom. His favorite was his younger brother, Cornelius — Con, for short — who he named “the gassoon,” an Irish term for a youth.

As “King of the Potrero,” Frank McManus held himself above the law of the common people.

He was often arrested for drunkenness, fighting and attempted murder, but he always got the charges dismissed — either through fear or political power. As a kind of noblesse oblige, he would plead guilty for using bad language and pay a $10 fine.

Instead of a jester, Frank had a 300-pound black bear, chained in his back yard, as part of his retinue.

The bear participated in the numerous drinking bouts of the royal court. After one of these bouts, the besotted bear ripped his chain loose, wandered into the second floor of a nearby rooming house and got into bed with a man who was similarly soused. The man, thinking his friends were joking with him, started hitting the bear until the bear returned the favor. Suddenly, the man awoke and, realizing the bear was not a hallucination, started screaming.

His screams woke the rooming house, and the bear was returned to the king without causing any serious injuries.

Around 1890, Jack Welch and his brothers, fellow Irishmen who had honed their political skills in the rough-and-tumble world of Tammany Hall politics, arrived in the Potrero. Jack and his brothers opened a boarding house around the corner from Frank’s place.

Jack, who was a Democrat, attracted a large group of men who had been chafing under Frank’s rule. Thus began the “Blue Mud Wars,” named after the blue rocks that would turn to mud during the fighting. This war was won during the bloody 1891 primary, when the Welch faction decisively defeated the MacManuses, and the Democrats won the day. More than 100 men were involved in the fighting that day.

King Frank, however, refused to accept defeat, and a war of attrition followed.

On June 25, 1892, Frank and his followers dragged Jack out of the carriage he was riding in on 3rd Street. Con McManus stabbed Welch, and Welch pulled out his pistol and shot Con three times. Though seriously wounded, both men survived.

On June 14, 1894, fellow ballplayer Charles Sweeney was attacked by Con in a 3rd Street saloon. During the fracas, Sweeney shot the gossoon three times, killing McManus. The death of his brother drove Frank wild. He tried to get into Sweeney’s hospital room to kill him and had to be restrained by six policemen.

When the priest refused to perform a high mass during Con’s funeral services, Frank threw a brick through the church’s window and threatened his life. Despite testimony that Con had been the aggressor, Sweeney was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to eight years in prison.

The death of his brother devastated Frank and caused him to increase his already Herculean drinking. Within two years, he had wasted away to 130 pounds and died of congestive heart failure. Irish Hill disappeared after World War I, when industrialists bought the hill to expand their businesses. The hill was leveled and dumped into the Bay.

About the Author:Paul Drexler has been a crime historian since 1984 and founded Crooks Tours of San Francisco with former SFPD Deputy Police Chief Kevin Mullen. His column, “Notorious Crooks” has appeared numerous times in the San Francisco Examiner and other publications. He has appeared on the Discovery ID Network show Deadly Women as an expert on San Francisco murderesses. In 2017 he received the Oscar Lewis Award from the San Francisco History Association. His book, San Francisco Notorious will be published by R.J. Parker Publications in 2019. His website is www.crookstour.com.

Read more from Paul Drexler: