By Robert Walsh

Les Bourreaux enjoyed (or endured) two distinct phases before and after the French Revolution of 1792. The Revolution brought many changes, but one thing never altered. They were the most despised, reviled and feared men in all of France. Hardly surprising, given their occupation, but not entirely fair and gross hypocrisy as well.

In pre-Revolutionary France executioners were chosen on a regional basis. In keeping with their public image they were drawn from people already performing work regarded as distasteful, unpleasant and only for the lowest rung of France’s social ladder. Undertakers, tanners, gravediggers and saddlers often found themselves shoe-horned into a part-time job that nobody else would take, that of torturer and local executioner. If nobody else was prepared to do the job then condemned criminals were offered it, spared their own lives in return for taking those of their peers.

When ordered they hung, drew and quartered, beheaded, burnt, broke on the wheel and hanged condemned prisoners. They also cut the hands off thieves and dismembered the condemned for public display, if ordered. Before a decree in 1791 they also tortured the condemned before execution if that was the sentence.

Beheading was often reserved for members of the aristocracy who usually died by the sword as a mark of their social status. Anne Boleyn, executed wife of England’s Henry VIII, died on his native soil, her husband importing a French executioner and his sword for the occasion. The social status of ‘Les Bourreaux’ wasn’t in any doubt, either. Universally feared and loathed, the executioner was also a breed apart and while happy to watch his hand sever necks, tie nooses and light fires under heretics, most French people weren’t inclined to shake it.

As much as executions were a public spectacle, the bourreaux lived in isolation. Schools routinely refused to teach their children. Merchants wouldn’t sell them goods. Employers seldom employed them. Traditionally nicknamed for the towns where they lived and worked, executioners were frequently made to live outside them. ‘Monsieur de Rennes’ might dispense justice both in Rennes and most of Brittany, but living in Rennes itself was out of the question.

Bakers followed an old French superstition. Obliged by law to provide bourreaux with free bread they kept it on a separate shelf, turned upside-down as inverted bread apparently attracted the Devil. Executioners also had to wear some badge of office, usually an image of a gallows or sword. Marking them as pariahs, Jews, prostitutes and vagrants also suffered a similar indignity.

Socially ostracised by virtue of their profession, the Church added to their outcast status. Bourreaux were only allowed to marry into the families of other bourreaux so, by abolition in 1981, all French executioners for centuries could be traced through a handful of family trees.

The few perks of the job couldn’t have compensated for the bitter irony of crowds turning out to watch them work one day only to spit on them in the street the next. So isolated were the bourreau families that one, the legendary Sansons, supplied six consecutive generations of executioners while their extended family supplied even more.

There were perks, though, albeit largely to ensure they had the means of daily living. An executioner possessed by law the right to levy certain goods from local merchants, even those who refused to actually sell them anything. Bread, vegetables, meat, fish and others goods could be levied according to the bourreau’s ‘droit de havage,’ the appropriately named ‘right of cleaving’ or ‘right of chopping.’

Related: France’s Lonely Hearts Serial Killer and the Strange Case of the Missing Notebook

An executioner could take, for free, as much of those goods as his two hands could hold. The Revolution would change much for the bourreaux, public hypocrisy didn’t. Until the execution of Eugen Weidmann in Paris in July, 1939 the French public enjoyed watching the bourreaux work while shunning them everywhere else.

From 1791 torture before execution was abolished and from then on there would be only one executioner for each French region or ‘departement.’ Assistant executioners (known as valets) were also abolished in the departements. Again Paris was the exception ‘Monsieur de Paris, required by law to reside in the city, retained several valets.

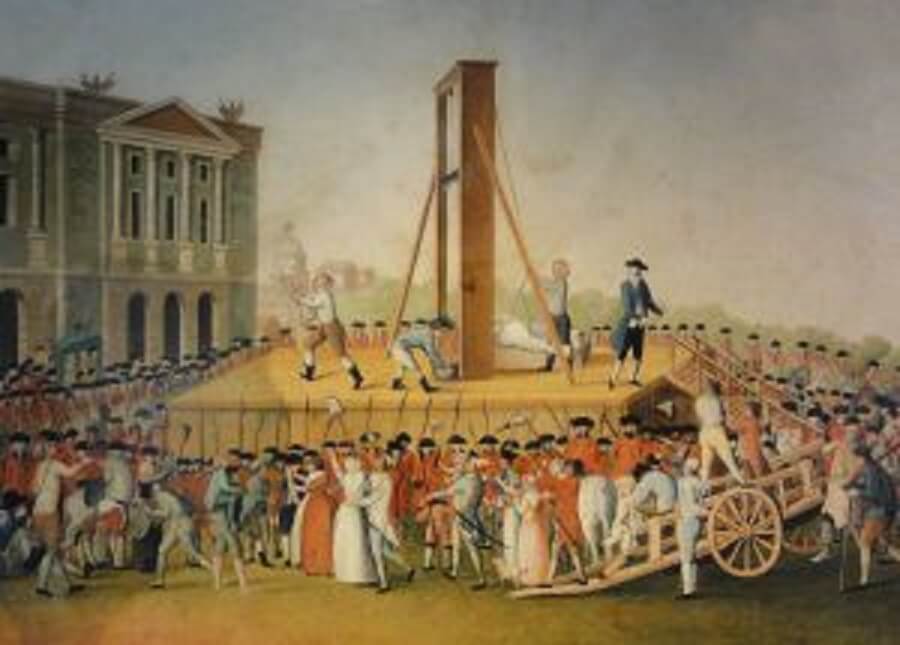

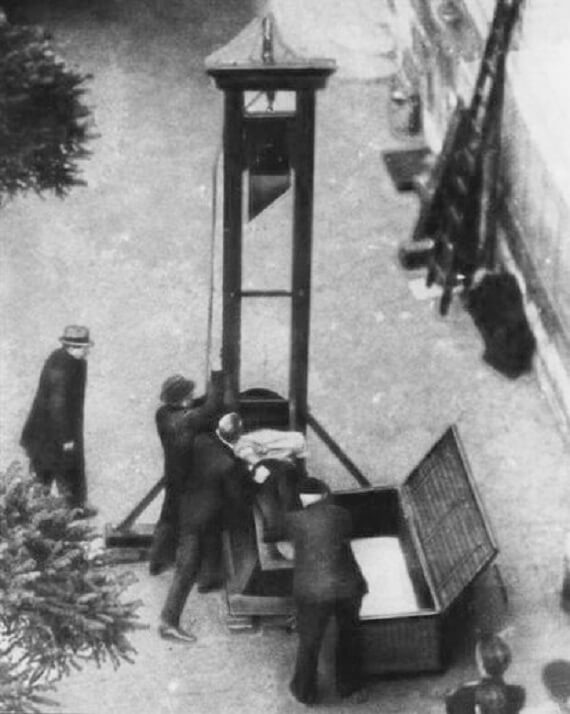

Different methods of execution were also abandoned. From then on, as both a humanitarian and social statement, every prisoner would be beheaded in the same way. Whether prince or pauper, all would face a brand-new invention regardless of social distinction;

The guillotine.

Known variously as the ‘People’s Avenger,’ ‘National Razor,’ ‘Timbers of Justice,’ ‘Madame la Guillotine’ and ‘The Widow’ it replaced the wheel, gallows, sword, axe and burning post. The executioner’s torture tools also became museum pieces. The bourreaux did not; They were never more well-known or less unpopular than when providing vengeance-by-proxy for their proletarian public. They were never as busy, either, sometimes killing a hundred or more aristocrats a day and over 3000 in a single month. First used on highway robber Nicolas Jacques Pelletier in Paris on April 25, 1792 it wasn’t an instant success.

With Pelletier public hypocrisy reached new heights. Far from promoting the bourreaux as no longer being savages and outcasts, the spectators complained that it was too quick and humane. They even came up with a then-popular song including the words ‘Give us back our wooden allows.’ The public might have regarded those who worked such instruments as the lowest of the low for doing so, but they hated even more the idea of being deprived of the entertainment factor from seeing prisoners strangle slowly at the end of a rope or be engulfed in flames. No, the bourreaux were still unholy brutes. It was just that were no longer brutal enough.

Until 1939 the heads still rolled, the crowds still turned out and the bourreaux were still objects of public hatred. By then use of the term ‘bourreaux’ had been officially outlawed (not that anyone stopped using it) while French officialdom too sought to distance itself from those who did their dirty work. The guillotine itself was officially the property of the chief executioner, not the Ministry of Justice. The chief executioner (now only ‘Monsieur de Paris actually dropped the blade) and his remaining valets were also kept at arm’s length.

‘Monsieur de Paris’ didn’t draw a salary. He was given an annual appropriation of 180,000 Francs to cover repairs, maintenance, expenses and paying himself and his assistants. The Ministry of Justice could then keep them all at an official distance while still regularly despatching them around France, themselves to despatch the criminals thereof.

The pay was low and one chief was fired for having pawned the device to raise funds. When they found out he’d done so, shortly before a scheduled execution, the Ministry had to redeem the pawnbroker’s fee out of public funds so the execution could go ahead. In their eyes, however, nothing could redeem the bourreau who’d pawned it. He was immediately fired.

In France’s notorious penal colonies at French Guiana and New Caledonia the National Razor’s operators were equally hated, though for a different reason. The penal colonies used convict-executioners, men already serving sentences who were ready to kill their fellow criminals in return for protection and privileges. Hated by guards and inmates alike, they were the most reviled convicts in the system.

Neither guards or inmates had any time for men viewed as traitors to their criminal class. A couple were themselves executed. Isidore Hespel, known throughout Guiana’s Penal Administration as ‘The Jackal’ was himself executed for murder by the very assistant executioner he’d trained. The assistant wasn’t any more popular for having executed his hated boss.

Worse still was the grisly fate of a particularly brutal Guiana bourreau Henri Clasiot. A man of singularly vile personality, Clasiot routinely beat, cursed and insulted the convicts he executed, marching them to the guillotine with fists and invective. Abducted by some freed convicts, Clasiot found himself facing far worse than even he had inflicted. After a severe beating, his captors stripped him naked, smeared him liberally with honey and staked him out over an anthill.

The ants were carnivorous.

1949 saw France’s last female execution, that of Germaine Leloy-Godefroy. In 1953 the last prisoners returned from Guiana, the infamous colony having closed its doors in 1946 and its caps and orisons gradually shut down. A movement against capital punishment had always existed in France, but it gathered increasing momentum after World War II. Ironically considering their profession, now the bourreaux themselves were on borrowed time. After Weidmann in 1939, itself watched by a young Englishman later to become Sir Christopher Lee, executions were hurriedly removed behind prison walls. Such had been the disgust at drunkenness and debauchery during Weidmann’s death, President Lebrun (an opponent of capital punishment) ordered public executions abolished. The bourreaux became increasingly obscure and secretive figures, perhaps grateful for the lowering of their public profile. The penal systems of Guiana and New Caledonia closed and, while ‘Monsieur de Paris’ and his valets still plied their grim trade, they did so increasingly rarely and entirely in private.

1977 saw France’s last execution, that of Hamida Djandoubi in Marseille’s notorious Baumettes prison. In 1981 the National Assembly finally abolished the death penalty. Djandoubi was the last prisoner beheaded in both France and Western Europe. France was the last in Western Europe to abolish beheading as a method. The days of ‘les bourreaux’ were over.

Until abolition French judges still passed death sentences, but all were commuted. Seeing the way the political wind was blowing President Francois Mitterand (another death penalty opponent) reprieved every death sentence passed between his election and final abolition. No longer would the residents of what the French called ‘Death Alley’ count off the days they had left and wonder how many actually remained.

French condemned prisoners were never given their exact date and time of execution until it actually happened, when at the traditional time of dawn their cell doors opened and their final walk began. They knew when there was an execution scheduled for the next morning, but whose? They spent every dawn hoping the door that opened wouldn’t be theirs.

No longer would they hear guards talking in the evenings and tremble until after the dawn, having heard the dreaded words ‘Monsieur de Paris est ici…’

‘The Man from Paris is here…’

About the Author: Robert Walsh is a freelance writer specialising in true crime. His work has appeared in Real Crime Magazine, Sword & Scale, Executed Today and his own blog Crime Scribe is an excellent resource full of historic gems covering true crime and criminal justice, a highly recommended read. This article is kindly republished from Crime Scribe with permission from Robert and the original article can be read here.

![An Innocent Man [Part III]: The Trial of Dr Jeffrey MacDonald – A Critique of the Case](https://www.crimetraveller.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Jeffrey-Macdonald2-324x235.jpg)