Would you believe that the main character in one of literature’s most celebrated 19th-century novels appeared in San Francisco in 1948? The novel was Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.” The character was Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov. And his 20th-century incarnation was William Sanford. What follows includes a brief summary of “Crime and Punishment.” In the interest of simplicity, eight major characters have been omitted.

“Crime and Punishment” focuses on a murderer, Raskolnikov. He is 23 years old and described as “exceptionally handsome … slim … with beautiful dark eyes and dark brown hair.” Throughout the book, we hear Raskolnikov’s inner thoughts and his justifications for his actions. He is a bright but penniless ex-student who has been living on money borrowed from his mother and sister. Raskolnikov thinks of killing an old lady, Alyona Ivanovna, an avaricious moneylender, and justifies it by arguing that he is doing so for the greater good. The woman has been cheating people and ruining their lives. She will die of old age soon, anyway. With the money he steals from her, he will help others, including his mother and sister. Raskolnikov murders Ivanovna with an axe and then kills her sister when she comes home unexpectedly. He is so rattled by this that he flees the house, leaving most of the loot behind. The next day, he takes the money he stole and buries it under a rock.

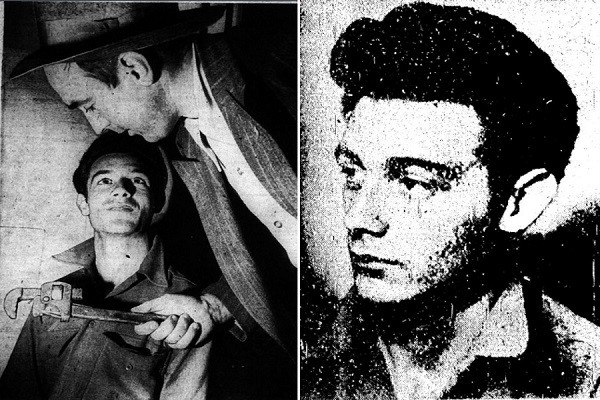

William Sanford, Raskolnikov’s 20th-century embodiment, was an excellent student as a child and won honors at St. Peter’s Parochial School. His behavior changed dramatically in adolescence when his mother, father, and sister died. Sanford was arrested for theft in 1944 and for armed robbery in 1946. He had dark eyes, and dark brown hair and was described as having a “thin aesthetic face.” In 1948, at the age of 20, Sanford escaped from the California Youth Authority and moved to a rooming house owned by Felippa Griffith, an old widow, whom he murdered.

Sanford later told police his justifications for killing Griffith:

“I killed that old lady because over a period of years I made myself believe I had no willpower — that commission of a murder completed a fatalistic design. I told myself I had to kill Mrs. Griffith … I had to get rid of her so I could rob her and get enough money to buy a gun to kill the girl who had thrown me over. … I had nothing against the old lady. Her death merely constituted a means toward an end. Actually, you know, she is better off dead. Her husband died. Her son was killed in the war. Her grief was driving her crazy. She had to work like a dog and was tired.”

Sanford used a heavy wrench to beat Griffith to death. He then ransacked her room, taking $1.50 and all her jewelry. As he was about to leave, he tore the rent receipt with his name on it out of Griffith’s receipt book. Sanford then went to a beach, put the valuables in a handkerchief, and buried it in the sand.

At this point, truth and fiction diverge. Raskolnikov spends the next 34 chapters drinking, thinking, and suffering as only a Russian can do. He dithers between a need to justify his actions and a guilty desire to confess his sins. Finally, after much soul-searching and pleas from Sonia, the woman who loves him, Raskolnikov realizes his sin and confesses to the police.

Sanford’s arrest occurred much more quickly. Ironically, it was the page with the missing rent receipt that led to his capture. Police focused on the missing page, and learned that Griffith could not write English and that Harry Cohen, one of her roomers, filled out the receipt book. Cohen recalled that the name “Bill Sanford” was written on the missing page. Police canvassed other rooming houses and arrested Sanford within two days.

Sanford was unrepentant. “I had a complete realization of what I was doing,” he said. “If I had it to do over again, I would repeat my act. Only I would kill Mrs. Griffith in a different fashion.” He was also determined to die. “I want to assure myself of the gas chamber,” he said. “I couldn’t endure spending the rest of my life in San Quentin.”

At Raskolnikov’s trial, he pleads insanity, and after evidence of his good deeds is shown, he is sentenced to eight years in Siberia. Sonia also moves to Siberia. After a while, Raskolnikov falls in love with her and they look forward to being together when he is released in seven years. This is as happy an ending as you are going to get from Dostoevsky.

At Sanford’s trial, he pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and asked for a death sentence. The judge and jury obliged. His execution was scheduled for Nov. 15, 1949. The night before his execution, Sanford played a recording of the “Bluebird of Happiness” again and again. He died at 10 am. the next day.

About the Author:Paul Drexler has been a crime historian since 1984 and founded Crooks Tours of San Francisco with former SFPD Deputy Police Chief Kevin Mullen. His column, “Notorious Crooks” has appeared numerous times in the San Francisco Examiner and other publications. He has appeared on the Discovery ID Network show Deadly Women as an expert on San Francisco murderesses. In 2017 he received the Oscar Lewis Award from the San Francisco History Association. His book, San Francisco Notorious will be published by R.J. Parker Publications in 2019. His website is www.crookstour.com.

Read more from Paul Drexler:

- The Baby Bandits of San Francisco

- California’s Queen of Grudges, Isabella J. Martin

- The Hair-Raising True Tale of John “Chicken” Devine

- Frank McManus: King of the Irish Hill