Australian true crime writer Stephen Karadjis takes an in-depth look at the 1971 Qantas Bomb Hoax carried out by the mysterious ‘Mr Brown’, later revealed as Peter Macari. Followed by a rethink of the D.B.Cooper case that took place just six months later – ‘Remembering D.B Cooper’ – (A Minute by Minute Reconstruction)

On 24 November 1971, the infamous ‘D.B Cooper’ (whose identity remains a mystery) hijacked a Boeing 727 commercial airliner and was paid a ransom of US $200,000. He deployed the rear staircase of the plane and with a parachute in situ, leaped into the black abyss of night, never to be seen again. Six months before this foolhardy heroism by this mystical figure – there was another audacious act of air piracy.

As an impressionable ten-year-old in the 5th Grade at Leichhardt Public School in Sydney’s inner western suburbs, it was going to be a big day. Along with other boys and girls, we were heading off on an excursion to Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith International Airport. We were being shown around inside a brand-new Boeing 747 “Jumbo-Jet.” I remember thinking how big the interior of the plane was, and how it could possibly get off the ground. All of a sudden, police rushed the airliner and evacuated teachers and pupils to a safe zone.

This is the story of extortionist Peter Macari and what became known as the “Qantas Bomb Hoax” – Australia’s greatest-ever heist.

“Mr. Brown” Telephones the Department of Civil Aviation

At 11 am on Wednesday 26 May 1971, a man calling himself “Mr Brown” telephoned the Department of Civil Aviation. The call was transferred to an on-duty Commonwealth policeman. “Mr Brown” said there was a bomb in Locker 84 at Sydney’s Kingsford-Smith International Airport.

The device was said to be a “24-stick gelignite barometric bomb” and identical to a second bomb planted on board a Boeing 707 Qantas-Jet (Flight 755) bound for London via Hong Kong.

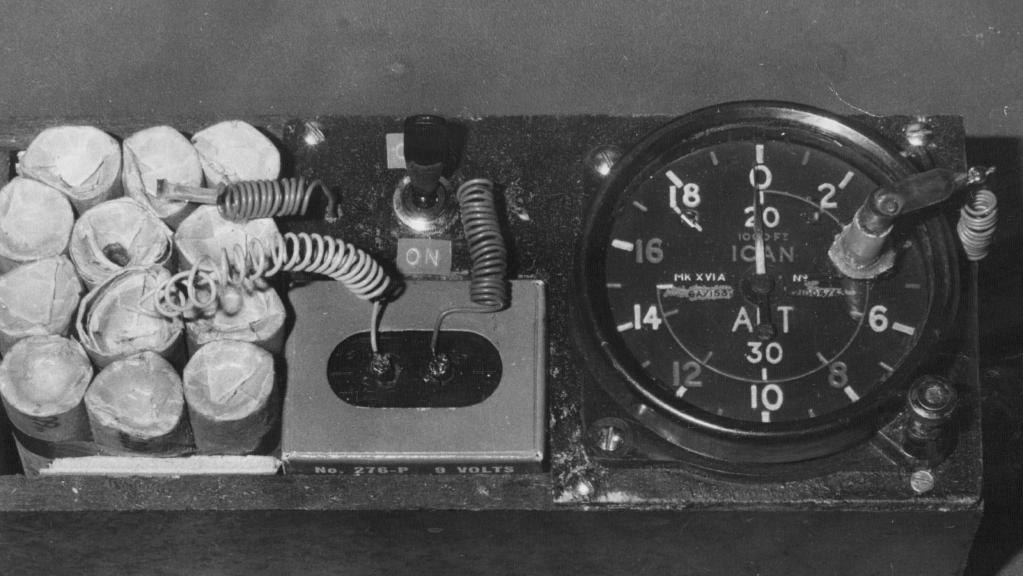

When the bomb squad opened the locker, they were relieved to discover the explosive device was not activated. However, the Commonwealth Police quickly realized the significance, because although it was not live, it had been assembled by a person obviously skilled in bomb-making. The construction included an altimeter, gelignite, and detonators. There were also three notes found inside the box that housed the bomb.

The first was addressed to Captain R. J. Ritchie, a Qantas General Manager, with a demand for $500,000 in ransom, in exchange for instructions on how to de-louse a larger and far more powerful “altitude-bomb”. The second letter was addressed to Sergeant Short of the Commonwealth Police, reiterating that a larger explosive device was aboard the aircraft bound for Hong Kong. The third and final note gave a dire warning, that should the plane descend below 20,000 feet, the bomb would explode.

The office of the Prime Minister (William McMahon), the NSW Premier (Robert Askin), and the Minister for Civil Aviation (Senator Cotton) were advised of the developing situation. The Army and Navy were galvanised, and ships, submarines, helicopters, and amphibious vehicles, along with experts in bomb disposal and air-sea rescue, were moved into position. A navy screen of nine warships drawn from Broken Bay to the north, Garden Island in Sydney Harbour, and Jervis Bay on the south-coast, patrolled inside Botany Bay (the location of the airport terminal) and ten miles out to sea.

At the outset of the drama, unfolding in the skies above Sydney, the immediate concern which took the highest precedence was the lives of the 116 passengers and 12-crew on board Flight 755. A radio link was quickly established with Captain William “Bill” Selwyn, at the controls in the cockpit of the Boeing 707.

With 13 years accrued flying time, Captain Selwyn, 49, was told to continue north for the city of Brisbane Queensland (in the direction he had been heading), and to await further instructions. However, this directive was swiftly countermanded when it was realised Sydney Airport was superior in capacity and capability for emergencies.

On the re-routed journey back to Sydney, Captain Selwyn maintained an altitude of 35,000 feet and a minimum cruising speed in an effort to conserve precious fuel. Prior to being diverted homeward, the crew began a frantic and intensive search of the jet, to pinpoint the location of the bomb. For the next six hours the high stakes drama played out with the plane circling the skies above Sydney, off the east coast of mainland Australia.

Threat to Set Off “Altitude-Bomb”

Captain Selwyn was an inveterate jet pilot with thousands of hours of flying time under-his-belt and an empirical knowledge of Boeing 707 cockpit operations. His role, in this instance, was to keep the plane in the air and delay landing for as long as possible, until negotiations were made and the ransom demand was met.

The two key figures in the delicate negotiations (received by telephone), were Qantas General Manager Captain Robert James “Bert” Ritchie, and Deputy General Manager Mr. Phillip Howson. When the first call came in from the extortionists asking to speak with Captain Ritchie (who was out of his office at the time), Deputy Howson represented himself as the Qantas General Manager.

As the negotiations got underway, a Qantas executive wrote a cheque for $500,000 on the Reserve Bank and a dozen senior executives began counting and bagging the bundles of $20-notes (the highest denomination of Australian currency at the time).

The operation took place within the Reserve Bank building in Martin Place at Macquarie Street (home to the city’s practicing-elite medical and law specialists), opposite the NSW State Parliament, Sydney Hospital – Sydney Eye-Hospital, and wedged between Hyde Park and the Royal Botanical Gardens.

The counting and bundling of the money continued throughout the afternoon. Staff only had time to record a minimal number of bank-note prefixes when the hoaxer made his move.

It was late in the afternoon, winter was fast approaching, and it was already dark outside when “Mr. Brown” set the ransom terms. By this time, there was only a one-hours supply of fuel remaining in the Boeing 707 still circling in the air.

The Pay-Off by Qantas ($500,000 Bomb Ransom)

To understand what $500,000 could buy in 1971, my parents purchased a house in a working-class locality of Sydney on 18 July 1971 at a cost of $14,400. It took them 10 years with both working to pay it off.

“Mr. Brown” spoke with Captain Howson at 2 pm, 3 pm, and 4 pm, each time with more instructions, always holding back some details and keeping officials in limbo. After a long wait, the call came through at 5:30 pm from “Mr. Brown” with the pay-off instructions. Qantas Deputy General Manager, Mr. Howson took the call as he had each time. The exchange lasted approximately nine minutes. It was now 5:36 pm. He was told a yellow van would pull up outside Qantas House in Chifley Square in the city at 5:45 pm. The driver was to toot the horn three times and wave the car keys out the window. There was a warning of irreversible catastrophe if there was any deviation. The getaway vehicle was not to be followed. To do so would mean detonation of the airliner and total loss of life. “Mr. Brown” said a second vehicle would be watching police. He also alluded that he was part of a larger criminal network and that he was simply the go-between.

Ready for the exchange, there were four police radio-patrolled, “shadow-vehicles” parked and waiting in Chifley Square.

Captain Ritchie made the rendezvous to deliver the ransom as the instructions dictated. It was unknown whether the extortionists knew the Qantas Chief Executive by sight, and for this reason substituting a police officer in his place was too great a risk to take. He handed the two blue suitcases containing the ransom to “Mr. Brown” through the front passenger-side window. The extortionist then drove away. Astonishingly, the getaway vehicle was not tailed. The van was discovered fifteen minutes later, parked at the corner of George and Bathurst Streets, opposite the Regent Theatre, in the heart of the city.

A technician had noticed a “mustard-colored” van being driven erratically along George Street, between Hunter Street and Martin Place. The traffic lights at the intersection of George and Bathurst Streets went to amber as the driver of the van shot across them, changing lanes abruptly, and cutting off a taxi-driver. He then applied the brakes hard and pulled to a stop. The man emerged from the van carrying the two blue suitcases. He then walked around the corner into Bathurst Street and headed off on foot in the direction of Hyde Park.

At 6:10 pm “Mr. Brown” telephoned Qantas officials a final time (from a public phone booth), to say there was no bomb on board the plane. Captain Selwyn was radioed with the soothing news and the airliner landed safely at 6:45 pm. For passengers and crew alike, the frightening ordeal was over.

Statements Later Taken from Crew and Passengers

Captain Selwyn recalled; – “We were going to stay as long as possible in the air and we were searching all the time. We pulled-off every conceivable panel and searched. The passengers remained calm and there was no panic at any time. This was the case even when the stewards and hostesses began ripping-up carpets and removing light-fittings.”

Mrs. Noeline Miller of Turramurra in Sydney’s eastern-suburbs said; – “The captain told us it was a technical-fault in the plane – but we couldn’t understand why they would be searching our luggage. We were just sitting there and all of-a-sudden, stewards, very apologetically, started to search our personal-luggage. There were a lot of young children and women aboard, but they all remained calm.”

Mr. Chester Antocks relayed that the Captain said they were; – “Looking for a small-object which shouldn’t be there. They asked if anyone had given us parcels before we left the airport.”

Mr. Hawes recounted; – “All the passengers helped in the search. We took the carpets off the floor.” He conveyed that the stewardesses were very calm and were joking with the passengers, that there was no panic on-board, but a lot of tension.

Mrs. Anna Leonardi and her two children were on their way to Rome to visit relatives. -“The children were scared, but not as much as me. I thought the object could have been drugs or a bomb.”

Mr. Charny (an importer) and his wife were travelling to Hong Kong. -“No-one took much notice, but when the search continued, and lunch wasn’t served, we began to wonder.” He then asked a steward what they were looking for. “He said it was a nine-inch-long-object. I thought immediately of gelignite. Then, half-an-hour before we were due to land they said, there was definitely nothing on-board to worry about. The last thing we expected to do tonight, was to sit here in Sydney Airport and eat”, said Mr. Charny, over a meal of steak and mushrooms.

Police Fumble and “Mr. Brown” Gets Away

Retracing the steps, at 5:40 pm Qantas General Manager Captain Ritchie announced that it was time to leave for the rendezvous with “Mr. Brown.” He walked from his office, through the lounge, and across the corridor into the Qantas secretary’s office, where the money was stored in a floor-to-ceiling safe and guarded by police and Qantas officials. Captain Ritchie recalled:

“As I picked up the suitcases, two policemen were heading for the lifts. It was mentioned that it might be better for them to take the lifts at the northern end of the building. They left at least 30 seconds before I walked down the corridor to the lifts at the other end of the building.”

Captain Ritchie said that he heard later that Detective Sergeant Jack McNeil at the time was on the telephone to the CIB (criminal investigation bureau) operations room, advising that the pay-off was about to go down.

Once he handed the two blue suitcases to “Mr. Brown” Captain Ritchie took the lift back upstairs to his office. Only a couple of minutes passed when Detective McNeil walked in and announced, “They’ve got away.” The Qantas General Manager was said to have been dumbfounded by the bungle.

A Comedy of Errors

The story goes that the police got stuck in a lift that had stopped at nearly every one of the nine floors on the way down to street level. Captain Ritchie said:

“But that didn’t really matter. They were never material to the surveillance of the van in the street. For a start, their cars were in the basement car-park. Their job as I saw it was to let the police in the street know when to move. They were the ones to apprehend the men. The whole play was to be acted outside Qantas House. Our job was to do as the criminals asked.”

No one it seems knows the whole truth, but it appears the policemen who were stuck in the lift were to signal the police in the four “shadow vehicles” to move in and block off the extortionist’s escape route.

Although police were reluctant to talk on the subject, the word getting around was that officers stationed at Qantas House were not given sufficient notice that the pay-off was about to take place, until it was too late. They blamed Captain Ritchie and Qantas officials for the bungle in failing to move in on time and prevent the extortionist’s getaway.

The Police Commissioner Speaks

Stories from The Sun-Herald on 6 June and The Sydney Morning Herald on 7 June by Graham Eccles, had Police Commissioner Norman Allan speaking. “It was a very well-laid plan. Unfortunately, the plan didn’t go the way in which it was designed, in that the van could not be kept under surveillance all the way to the spot when it was abandoned.”

He went on to say, that immediately following the pay-off police worked to cut off all escape routes out of the country and were hopeful the criminals responsible were still in Australia and for that matter, still in Sydney. He added “They are checking a thousand and one leads. Our top men honestly can’t leave it alone. They won’t put down the book. The whole case, despite the criminal aspect, is fascinating. It thrills every one of them and they simply won’t rest”.

In another news story, Commissioner Allen commented:

“Sooner or later the man is going to crack under the strain of what he has done, about what to do with half a million dollars. He’ll give himself away to someone or make somebody just that little bit suspicious. He may buy a car, new clothes, flash his wealth just a little to catch someone’s eye.”

The Investigation Gets Underway

The Criminal Investigation Bureau (CIB) had pooled its expertise and held some early suspicions. They thought “Mr. Brown” could be familiar with the aviation industry as he had displayed knowledge of commercial aircraft. He had shown himself capable of setting an altimeter to activate a bomb (detectives were working to trace the source of the various components of the device). They believed the hoaxer might have an association with Sydney Airport since he was aware that the plane on which he had planted the bomb had been changed on the day of the extortion. “Mr. Brown” also revealed inside knowledge that a Sergeant Short of the Commonwealth Police was on duty. Lastly, one of three notes to Captain Ritchie was addressed with both his correct initials.

The Premier, Robert Askin approved a recommendation by Commissioner Allan that a reward of $20,000 be offered for information leading to an arrest. The Prime Minister, William McMahon, added a further $30,000, bringing the total reward to $50,000.

A story from the Daily Telegraph on 31 May (“Police Making a “Mr. Brown” Dummy”) said that a police artist and sculptor, Detective-Sergeant Ken Brown, was creating a life-size model of the bandit, based on descriptions given by Captain Ritchie and the technician who pursued the getaway van.

On 2 June, the Chief of the (CIB) Detective Superintendent R.E. Lendrum, said that police had invited the Press and TV cameramen to photograph the creation. The next day, an Identikit picture taken of the finished model appeared in all Sydney newspapers in the hope it would jolt someone’s memory.

The description was of a man aged “25 years; 5 feet 8 inches; collar length brown hair; moustache and glasses; dressed in a mid-blue floral-pattern shirt, open at the neck with a deep modern collar; fawn coloured wind-cheater jacket; light coloured trousers with flared bottoms; wearing well-worn brown suede desert boots”.

A London newspaper, the Evening Standard, claimed the man in the Identikit picture was known to the Yard and that they had despatched fingerprints and a photograph of the individual.

On 1 June police parked the mustard-colored van at the corner of George and Bathurst Streets to recreate the scene in the hope that someone might recognise it or remember having seen the vehicle elsewhere on the day of the bomb hoax. Officers had 2,500 flyers printed with a series of questions, which they handed around to the public.

The fact that no one from organised-crime elements in Sydney or Melbourne had come forward to their police contacts indicated to authorities that “Mr. Brown” and his gang were not connected to Australian criminals. For this reason, senior detectives were working closely with Scotland Yard in Britain, Interpol in France, and the FBI in the United States, and all three agencies were feeding back information to Australian police.

Police also sought assistance from academics working in phonetics at Sydney University. They were asked to listen to tape recordings of “Mr. Brown’s” voice. All concurred the voice was most likely from mid-England with a twang of North London. Captain Ritchie said the man who took possession of the ransom, spoke with an Australian accent, so detectives surmised that the person who drove the van was not “Mr. Brown” but an accomplice.

It was discovered that the type of gelignite and detonators used in the bomb were only used at the Mount Isa Mines Limited in Queensland and a Western Australian mining company. Consequently, a team of detectives flew to Queensland to further investigate. Detective Sergeant Fred Krahe said, “We have quite a few suspects here.” Police were of the opinion, that “Mr. Brown” had worked at the Mount. Isa Mines.

The Arrest of “Mr. Brown”

Two men were apprehended on 4 August 1971. At a specially convened press conference the following day, the Chief of the CIB, Detective Superintendent R.E. Lendrum, announced that a 31-year-old fiber-glass factory owner and driver, originally from Devon, England was “Mr. Brown”, and a 28-year-old Australian barman and former marine engineer was his accomplice.

Detectives had acted on a tipoff from a service station attendant about a “free spending” man, who had “set himself up in a lavish city residence in the last two months.” He was a regular customer and had pulled in for petrol in a new E-Type Jaguar. Some weeks later the same man pulled in with a new Ford GT. The attendant did not believe his story of good fortune.

Detectives of the Consorting Squad watched him. Later, they put a tail on a suspicious associate of the man. They stopped him in a new Chevrolet Camaro sedan at Burton and Victoria Streets Darlinghurst. “Mr. Brown” was then arrested. He was living in a new penthouse at 65 Fletcher Street, Bondi, for which he had paid $45,000. From the windows of the apartment, there was a panorama view of the blue Pacific Ocean.

A few hours passed and detectives from the Breaking Squad arrested the second man (whom police were tipped-off about) as he was parked and sitting in a late-model red Ford GT outside his flat in Llandaft Street, Bondi Junction. Later the same day, detectives impounded a Ford van located at a property in another suburb. It contained goods and tools. The two men arrested were due to appear in court the next day.

Superintendent R. E. Lendrum in charge of the investigation, had been assisted by a team of some of the state’s leading investigators. They included Inspector R. Stackpool, Detective Sergeants F. Kraha, J. McNeil, and A. Birnie.

On Friday 6 August, the men stood before Stipendiary Magistrate Mr. Murray. F. Farquhar in the Central Court of Petty Sessions in Sydney. The police prosecutor, Inspector V. Taylor, charged that a Mr. Peter Pasquale Macari was the person known as “Mr. Brown”. This was the man he said who had placed the bomb in the locker at Sydney Airport, made the telephone calls to Qantas officials, took possession of the ransom, and drove the van.

He charged that the second man, a Mr. Raymond James Poynting, assisted Peter Macari in the making of the bomb, wrote the three letters, and otherwise aided “Mr. Brown” in the operation.

An application for bail was made by Mr. R.J. Birney, counsel for the accused, and by Mr. M. Murray, counsel assisting the co-accused. The applications were denied. Magistrate Farquhar said he believed Mr. Peter Macari was a flight risk. He had a past history of absconding (while on bail in England he had fled and entered Australia on a false passport), limited personal ties to Australia and there was the sheer gravity of the offence. Mr. Poynting was held due to the serious nature of the offense. There was also $460,000 still missing. The men were remanded in custody until 12 August.

Police Discover $138,240 of the Ransom

On Sunday 8 August, two days after the court hearing, the Sydney Morning Herald ran a story titled, “$138,240 hidden in fireplace – MR. BROWN: HUGE HAUL FOUND”.

Shortly after the arrests in relation to the Qantas extortion case, CIB detectives became aware of a property, one of several they believed had been purchased by “Mr. Brown”. Police interest centred on a bricked-up fireplace in one of five empty rooms at the back of a butcher’s shop and residence in Trafalgar Street, Annandale, in Sydney’s inner western suburbs. The property was being renovated. A bricklayer working inside the house had tipped-off police that someone other than himself was responsible for a section of fresh work. He said it had been done one night the week before and that there was a fireplace behind the wall, which was now bricked up and cement rendered.

The tradesman had shown detectives the location in the room on Friday evening and police had assigned an officer to guard the residence that night. At 8:30 am on Saturday morning, a team of six detectives using sledgehammers, had smashed in the wall. Inside the fireplace was a cardboard carton (which once housed a toilet cistern). When they opened the box, they discovered two green disposable plastic garbage bags tied with rubber bands. They were stuffed with bundles of $20 notes. The detectives searched the rest of the property, breaking holes in the floors of each room and looking in the roof and the backyard. Despite a thorough search, no more of the Qantas’ ransom was found.

The money was transported back to CIB headquarters in Surry Hills in Sydney, where it was counted. The total came to $138,240. Police could now account for approximately $250,000 of the half a million dollars ransom. Detectives alluded that they were expecting a person (the petrol station attendant?) to make a claim for the $50,000 reward.

“The Doomsday Flight”

On 11 August 1971, The Sydney Morning Herald ran a story about a development in the United States.

Shortly before “Mr. Brown” pulled off his extortion plot, a film “The Doomsday Flight” aired on a Sydney television station. It depicted a familiar scenario of an airliner carrying a concealed bomb planted on board by an unscrupulous criminal who demands a ransom in return for information on the location of the device. Again, there is a caveat, that should the plane descend below a certain altitude the bomb would detonate.

The Federal Government in Washington D.C. had urged hundreds of television stations across the country to ban the showing of the film. It had been aired in Canada in July 1971.

A week later a man called to say a bomb was aboard a flight. Once again, there was a warning not to descend below 5,000 feet. The plane, travelling from Toronto to London was diverted to land at Denver Colorado airport, which sat at an elevation of 5,300 feet. It turned out there was no bomb, but authorities held concerns about future extortion plots.

Court Hearing for the Accused

On 5 October, the accomplice accused, Raymond James Poynting, pleaded guilty before Mr. W.J. Lewis, senior magistrate, at the Sydney Court of Petty Sessions. Detectives of the Breaking Squad gave evidence of interviews with the defendant in which he admitted his complicity. Along with Macari, he was charged with “causing a letter to be received, demanding money with menaces and without reasonable cause”.

On top of the above offences, the mastermind, Peter Macari was further charged with carrying a grenade at Sydney Airport on 26 May (the day of the hoax) and with stealing a Hertz rental van. A minor accomplice, Francis Sorohan, was charged with aiding and counselling Macari on or about 10 April to send the letter. He was employed at the Mount. Isa Mines.

On 6 October, evidence was heard against both Macari and Sorohan. Qantas General Manager Captain Ritchie identified the accused in court (Peter Pasquale Macari) as “Mr. Brown” and the man to whom he had paid the ransom. He had observed closely that the driver wore horn-rimmed glasses and what appeared to be a false beard, but what he most remembered was an extraordinary feature. The extortionist he said, was possessed of an aquiline or “hawk-like” nose.

Mr. Birney, counsel for Macari, raised doubt as to the true nationality of the van driver. Captain Ritchie had initially told police the driver was a well-spoken Australian. However, two days after the pay-off, he had changed his mind after listening to the taped telephone conversations between “Mr. Brown” and Qantas Deputy Captain Howson. He agreed with other Qantas officials that the man was English.

Detective Sergeant Williams of the police communications (electronics section) had played to a number of witnesses, the original tape recordings of 26 May, juxtaposed with recordings of “Mr. Brown” being dubbed by both English and well-educated Australian voices. As five months had passed since his conversation with the extortionist, the Qantas chief was now unsure.

On Friday 8 October, at the start of the day’s proceedings, Mr. Birney, speaking for his charge, stated that his client wished to plead guilty to the charges against him. He added that the defendant had listened to all the evidence produced in court and understood a trial was inevitable.

Magistrate, Mr. Lewer, allowed the police prosecutor, Sergeant R. Thomas to complete his testimony, advising that it was a better legal procedure to hear all the evidence.

The charges against the co-accused, Francis Sorohan, were dismissed. Mr. Lewer said that although Sorohan had stolen gelignite and detonators from his place of employment, the Mount. Isa Mines Limited, he was not satisfied the defendant was aware of the type of crime Macari had planned. For the explosives, he was paid a mere $100.

As the hearing concluded, Mr. Lewer said there was no doubt a prima facie case had been made against Macari. When asked if there was anything he wished to say, “Mr. Brown” replied, “I have nothing to say, sir.” He was then committed for sentencing at Sydney Quarter Sessions on all three charges.

“Where is the Missing Money?”

A 16-page record of interviews between CIB officers and “Mr. Brown” was tendered to the court by Detective Sergeant Jack McNeil. At the hearing and later at sentencing, the bomb-hoaxer was asked to explain the whereabouts of the missing money. About $261,382 had been recovered in cash, goods, and real-estate. As for the remaining ransom ($239,000), Macari had an answer.

He said there was a third-participant in the case and this man was the mastermind. He knew him only by the name ‘Ken’. It was he who asked him to make the bomb; had watched the “Doomsday Flight”; stayed in touch by telephone on the day of the extortion; and took all but $125,000 of the ransom. Macari said, “He threatened me and spoke of what some of his mates would do to me.”

“Mr. Brown” said that after being paid the $500,000 ransom, he left the stolen van at George and Bathurst Streets then walked west downhill to Kent Street (the technician saw him heading east to Hyde Park) to his own van. He said Ken and a second man were waiting in a white Valiant. Both parties then drove to Olive Street Paddington in the eastern suburbs. The suitcases were opened, and Ken took out the agreed $125,000 and handed it to him. He then put the lion’s share of the ransom in the boot of the car and drove away.

Police have no doubt Macari was the mastermind and that there was never any evidence of another key player. They say he gave $50,000 of the ransom to his accomplice Raymond Poynting and kept the rest. The best guess by police is that the missing money is underwater off Bondi Beach in two corrosion proof wall safes. However, this theory is doubtful and impractical. One would most likely hide the money where it was more easily accessible.

Prison

On 27 January 1972, the two guilty men stood in the dock of a hushed courtroom at Sydney Quarter Sessions. There was a large gathering of journalists and reporters in the press gallery and a handful of people in the public gallery. The proceedings were over in ten minutes.

“The circumstances of this crime are notorious. Your threat disrupted a major international air service and caused fears of imminent death to dozens of people.”

Judge Staunton sentenced Peter Pasquale Macari to a maximum 15 years in jail for pleading guilty to all three charges. He fixed a non-parole period of nine years. His accomplice, Raymond James Poynting, was handed down seven years for his part.

Release and Deportation

It was announced in the Sydney Morning Herald on Wednesday 12 November 1980 that “Mr. Brown” had been deported to Britain the previous night.

Following his release from Long Bay Jail, Peter Macari was driven under Federal Police-guard to Sydney Airport. The Department of Corrective Services would make no comment. The Minister for Immigration, Mr. Macphee, issued the deportation order as a matter of course. The Qantas extortionist had arrived in Australia in 1969 under a false name and passport. As there was a prior criminal record in his native England, he would not have been entitled to entry.

It was later reported that Peter Macari replied philosophically when asked about the whole affair, intimating that the nine years he had spent in prison was a high price and that crime did not pay.

- “A Certain Mr. Brown” – Less than a month after the Qantas bomb hoax, in June 1971, a pop song – “A certain Mr. Brown” performed by Peter Hiscock was released as a 45 rpm 7-inch single by Festival Records Australia. The song can be heard on YouTube.

- The Movie “Call Me Mister Brown” – In 1986, The Kino Film Company Limited in Australia released the television movie – “Call Me Mister Brown”. Directed by Scott Hicks and starring Chris Haywood it was based on the Qantas extortion plot. The film can be viewed on YouTube thanks largely to a philanthropist and is well worth watching. It is not available on DVD.

- Reference – The information contained in this article was sourced chronologically from the original newspaper reports by journalists working for the Sydney Morning Herald; The Sun-Herald; The Daily Telegraph; The Daily Mirror and; The Sun.

‘Remembering D.B Cooper’ – (A Minute by Minute Reconstruction)

It was 8 pm on 24 November 1971, and the infamous “D.B. Cooper” had just been paid a ransom of US $200,000 after hijacking a Boeing 727 commercial airliner. The passengers had all been allowed to disembark at Seattle Airport, leaving only the hijacker, pilots and stewardesses on board.

The jet was ploughing through the night-sky in a south-easterly direction, somewhere over Washington State in the American Pacific North-West. The weather outside the aircraft was bordering on cataclysmic. There was a powerful westerly following the plane. It was blowing at 200 miles an hour. The wind-chill was minus 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

Prior to departure, the pilot was instructed to de-pressurise the jetliner. Aware that this had been done, “D.B. Cooper” now unlocked the rear-door at the back of the plane. A sudden blast of air shot forward with tremendous force. The hijacker was blown off his feet. The rear-door instruction-placard immediately blew off into the night (it was recovered years later in mountainous terrain). The wind outside was an unexpected event and an unanticipated set-back for the hijacker.

The loss of pressure alerted the crew in the cockpit. The intercom came on, and the pilot asked the hijacker if he required assistance with the rear-staircase. He curtly refused. “D.B. Cooper” got to his feet and with the parachute and ransom already tied to his body and with the back-door open, deployed the rear-staircase. It lowered automatically. He was dressed in casual footwear and an overcoat (no protection from the wind-chill of minus 70 degrees). The hijacker then gripped the railings of the staircase tightly with both hands and made his way down to the last step, all the while the wind was pushing him back and pounding him front-on and directly in the face.

As he steadied himself, thoughts of abandoning the jump and retreating must have entered his mind, but his resolve was clearly stronger. He could not delay any longer in the freezing temperature. There was a window of minutes until hypothermia and unconsciousness. The situation was fraught with peril. There is no doubt that he knew once he let go of the railings he would be at the mercy of the wind.

As he released his hold and went to leap into the abyss, he was swept-up like a ragdoll in a tornado. The chances of him having pulled on his ripcord were next to nil, and he almost certainly spiralled to his death.

If by some miraculous good-fortune he managed to open his parachute, the chances he survived the jump were fair at best. The parachute might have collapsed immediately upon opening due to the force of the wind. As he dropped to the clouds he passed into a rain-storm. Again, the parachute might have collapsed. If he passed through unscathed there was still a problem.

The visibility was zero meaning no prior-warning of hitting the ground with no lights below. He was over mountain wilderness. If there were lightning-bolts he might have glimpsed what was awaiting him below, a huge body of water – the Columbia river. He was now hurtling towards it. If he was unprepared and did not see the water, he would have plummeted straight to the bottom and have been completely disoriented, not knowing in which direction the surface was located. He would have drowned. If he saw the water and could swim he could have made it to shore.

If he did make it, he was now bedraggled and freezing, with the whole night in front of him. He was also tens of miles from any civilisation. He most probably had no idea where he was, and uncertain in which direction to set-off on foot, once it was daylight.

So, did “D.B. Cooper” survive? The chances are remote. He most probably had no opportunity of opening his parachute due to the impact of the 200 mile an hour wind. It would have churned him up like a washing-machine.

The only part of the ransom ever to see the light of day, was discovered deposited under sediment on the river-bank, due to dredging of the river bottom.

It seems “D.B. Cooper” had a knowledge of aircraft, but was only a novice skydiver. An experienced practitioner would never have attempted the jump at night in such atrocious weather conditions.