The most damning piece of physical evidence used to prosecute Jeffrey MacDonald at trial in 1979 was the blue pajama top, with various arguments put forward regarding puncture wounds, fibers and bloodstains. The opposing findings between the FBI and CID of the blood stain patterns were not disclosed by the prosecution. Judge Franklin T. Dupree Jr. had swiftly ruled at trial that he would not allow the defense an opportunity to examine the documents and exhibits in question. By so ruling, the defense and the jurors knew nothing of their existence.

Helena Stoeckley’s Testimony – Ruled Inadmissible As Evidence

After testimony was concluded on the blue pajama top, Judge Dupree was required to rule on the (admissibility into evidence) the testimony of Helena Stoeckley, along with the witness testimony of several of her associates, to whom she had admitted her culpability in the murders. There were six witnesses in Raleigh, North Carolina, all of whom had come to court to testify for the defense. Some of these witnesses were very credible people, having worked in law enforcement.

As mentioned previously, a group of drug-addicted young hippies belonging to a satanic-cult became suspects on the very morning of the murders. Members included, Helena Stoeckley, 17, Gregory Mitchell, 19, a combat-hardened returned Vietnam soldier (who by all accounts was violent and had a short-fuse), a black male named “Candy”, who, according to Stoeckley had assumed control of the group and who was referred to as the “Wizard”, and Cathy Perry, 20, who later that year was detained in a mental hospital for stabbing two men on separate occasions and for attempting to stab the son of her landlady. Other core members of the cult, named at regular intervals by Stoeckley, include Dwight Smith, Shelby Don Harris and Bruce Fowler.

Helena Stoeckley, Gregory Mitchell and Cathy Perry each made separate confessions, independent of and without the knowledge of the others, at different points in time, to having taken part in the MacDonald family murders.

Over the years, Stoeckley had confessed to several of her associates. They included Fayetteville narcotics agent Sergeant Edward Prince Beasley; Nashville undercover narcotics police detective James Gaddis; a next-door neighbor William Posey who had testified at the Army Article 32 hearing; CID investigator Robert Brisentine; a work colleague, Jane Zillioux; Nashville music-promoter and associate Charles “Red” Underhill; and law clerk Wendy Rouder, hired as a personal assistant by defense attorney Segal at the time of the trial.

Judge Franklin T. Dupree Jr. again ruled against the defense. He did this by barring the witnesses from testifying in front of the jurors. He ruled that he would not allow Helena Stoeckley’s testimony to be heard by the jurors because he believed she was not a reliable witness. He had decided her testimony was not credible because of her history of drug addiction and through her own admission was heavily drug-affected the night of the murders. Instead, the judge heard her testimony in open-court without the jurors being present.

When Helena Stoeckley was called to the witness stand she did a backflip. She now denied any involvement in the MacDonald family murders. This was despite agreeing to testify to the contrary.

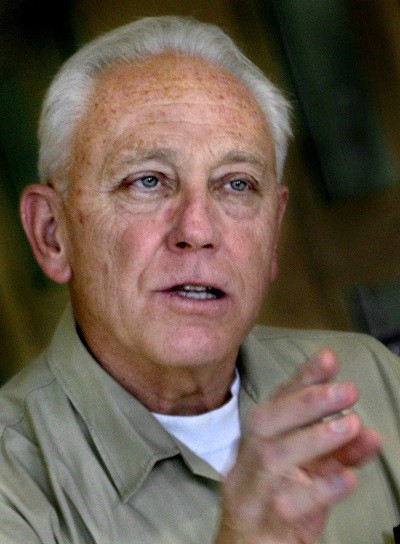

There is evidence to support the claim that the prosecution had threatened Stoeckley with indictment for the murders, if she admitted her complicity before Judge Dupree. A U.S. Marshall, Jimmy Britt, provided a statement under oath (many years after the trial) to having witnessed chief prosecutor James Blackburn threaten Stoeckley. Britt had transported Stoeckley to the courthouse in Raleigh. He was present in the room, where Stoeckley was seated, waiting to testify, when the threat was made. As a measure of good faith, Britt, in 2005, consented to sit for a lie-detector. He passed the examination.

Further corroboration of Stoeckley’s involvement came from Jerry Leonard. Judge Dupree himself had chosen Leonard to be the court-appointed attorney for Helena Stoeckley. In A Wilderness of Error-The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald, Morris writes, that when the two were alone, Stoeckley confided to Leonard the complete scenario of what had allegedly transpired on the night of the murders. This was the first time in nine years she had done so. She said that:

“She was a member of a cult with a core group of followers. One night one member of the group had raised the issue of Dr. MacDonald’s discriminatory treatment toward drug addicted veterans. MacDonald was one of the doctors involved in a treatment and counselling program. He had a hard stance and often refused to give methadone to heroin users. This member of the cult talked the group into going to the MacDonald residence to confront and intimidate him over his treatment. Consequently, they went to the house that night. But things got out of hand and the people she was with committed the murders.”

Author, Errol Morris, contends that Stoeckley’s confessions to Leonard are credible. He states they were, “detailed and given to an officer of the court and under the protection of attorney-client privilege.” Stoeckley had always said, that she would tell the truth, if she was offered immunity from prosecution. Morris believes Jeffrey MacDonald would never have gone to prison if Stoeckley’s testimony had been heard by the jurors and not ruled inadmissible as evidence.

Helena Stoeckley died from ill-health in 1983, at the young age of 31. Prior to her passing, she confessed her involvement in the murders to her mother. In 2007 Mrs. Stoeckley was living in a nursing-home. She signed an affidavit to her daughter’s death-bed confession. Mrs. Stoeckley said:

“My daughter knew she was dying and she wanted to set the record straight with her mother about the MacDonald murders and that she wished she had not been present in the house and knew that Dr. MacDonald was innocent and she told me she was afraid to tell the truth because she was afraid of the prosecutor.”

She was referring to chief prosecutor, James Blackburn. Blackburn, incidentally, was disbarred in the 1980’s from practicing law, over another matter, and sent to prison.

Testimony of the Witnesses to the Admissions of Helena Stoeckley – Ruled Inadmissible As Evidence

As a matter of course, her now changed testimony and denial of involvement before Judge Dupree led to her being excused from further testimony. Defense attorney Segal then went to call the first of the six witnesses to her confessions. However, assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh objected on grounds that such confessions was “hearsay evidence.” Following some legal tussle, Judge Dupree said he would hear for himself what the witnesses had to say without the jurors being present.

First up, Sergeant Edward Prince Beasley gave evidence that Helena Stoeckley had said she believed she had been in the house that night and had stated, “in my mind I saw this thing happen.”

William Posey repeated Stoeckley’s words to him, “although she did not kill anyone herself, she held a light”, that she saw “a hobby horse thing…which was broken.”

Jane Zillioux reported that Helena had stated, whilst in an emotional state, “she couldn’t return to Fayettville because she was involved in the murder of a woman and two children,” and had said, “so much blood. I couldn’t see or think of anything but blood.”

Charles “Red” Underhill gave evidence that when he visited Stoeckley she was crying and inconsolable and had said, “they killed her and the two children…they killed the children and her.”

Nashville police officer James Gaddis was asked by Judge Dupree “on the basis of what this girl told you, had these murders happened in Nashville, would you have issued or signed a warrant for her?” Gaddis replied, “I’m not sure, sir. I have a feeling I would have tried to have her indicted.” Then, after a pause, “I would have investigated further, and I would have indicted her, yes sir.” It should be repeated here that Stoeckley had worked as an informant to Gaddis. Such a relationship is built on mutual trust and respect and forms a strong bond.

CID polygraph expert Robert Brisentine gave evidence that she had confessed to him being present during the murders and had mentioned the amount of blood on the bed and that the hippie element was angry with MacDonald because he wouldn’t treat them with methadone. He added that, “since the deaths of Mrs. MacDonald and her children she had suffered nightmares and, due to frightening dreams she is afraid to sleep.”

“She knew the identity of the persons who killed Mrs. MacDonald and her children and that if the army would give her immunity from prosecution she would furnish the identity of those offenders who committed the murders and explain the circumstances surrounding the homicides.” – Polygraph Expert Robert Brisentine

Brisentine added an intriguing caveat from Stoeckley. He said she had mentioned that, “it had only been drizzling rain and did not start to rain hard until after the homicides.” He thought it revealing that on one hand she feigned any memory of the night but could remember the detail of when it started to rain hard. He thought this was truly telling of her having been at the murder apartment at the time.

Once the witness testimony concluded, in closed-court, before Judge Dupree, a great deal of legal argument ensued between defense attorney Bernard Segal and assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh. But, after much legal dispute, Judge Dupree ruled that the admissions Helena Stoeckley had made to these witnesses were, “clearly untrustworthy.” As a result, he did not allow the witness testimony to be heard by the jurors.

Years after the trial, an appeals judge, Francis Murnaghan, Jr. said that if he had been the judge he would have allowed the jurors to hear this testimony on grounds that:

“My preference derives from my belief that, if the jury may be trusted with ultimate resolution of the factual issues, it should not be denied the opportunity of obtaining a rounded picture, necessary for resolution of the large questions, by the withholding of collateral testimony consistent with and basic to the defendant’s principal exculpatory contention.”

The Psychiatric Issue at Trial – Ruled Inadmissible As Evidence

The last issue to be argued legally at trial was Jeffrey MacDonald’s previous psychiatric assessments and the question of their admissibility into evidence.

As disclosed in the previous section on the Army Article 32 hearing, he was subjected to a series of examinations after the murders in 1970. In “Fatal Justice-Reinvestigating the MacDonald Murders,” the authors relate that defense attorney Bernard Segal had surmised that, “the sheer brutality of the murderer or murderers of the MacDonald family indicated that whoever did it was sick, really mentally ill.” Segal had retained Dr. Robert Sadoff, a prominent psychiatrist. Sadoff had subjected MacDonald to a thorough psychiatric examination. He then instructed clinical psychologist Dr. James L. Mack to put MacDonald through another thorough battery of psychological tests.

Dr. Sadoff testified at the Army hearing that MacDonald was, “normal, sane, and not of the personality type to have committed the murders.” He also reported that, “his sadness, more than sadness but actual depression was accompanied by difficultly sleeping, some problem in eating, some irritability, and he was prone to tears in discussing the events of the night of February 17th. He was reacting to the deaths by what I would consider a normal depression.” He added:

“Based on my examination of him and all the data that I have, Captain MacDonald does not possess the type of personality emotional configuration that would be capable of killing his wife and children and react the way he did during my examination of him.” Dr. Sadoff was quoted as saying, “you can’t really destroy them the way these people were destroyed without being extremely disturbed in a number of ways…this was so horrific it would leave a trail a mile wide…and that trail isn’t there.”

During the army hearing, Colonel Rock had sent MacDonald on to Walter Reed Army Hospital in Washington D.C. for a separate round of testing, since Dr. Robert Sadoff was a civilian psychiatrist. He was assessed by the army’s best psychiatrists. They included, Colonel Bruce Bailey, chief psychiatrist; Lieutenant Colonel Donald W. Morgan, director of research psychiatry; and Major Henry E. Edwards, chief of psychiatric consultation. Dr. Bailey on behalf of Walter Reed concurred with Sadoff and Mack that MacDonald was not of the personality type that was likely to kill. He also added that in his opinion he was neither deranged nor fabricating his version of events.

The importance of MacDonald being examined thoroughly, by the best minds, within weeks after the murders, cannot be overstated.

Even so, in preparation for trial in 1979, defense attorney Bernard Segal resolved to send Jeffrey MacDonald for a new round of psychiatric testing. He retained Dr. Seymour Halleck, a forensic psychiatrist working locally at the University of North Carolina. Halleck concurred with Dr. Sadoff and Dr. Bailey reporting, “he was not of the personality type to have murdered his family.”

On the very first day of trial, assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh approached the bench out of hearing range of the jurors. He entreated Judge Dupree to disallow all psychiatric testing, based on what he said was his concern the subject would “permeate the trial.” Chief prosecutor James Blackburn pressed the point that should the prosecution be able to prove MacDonald did the crime then there would not be a need to prove that he had the personality type to have committed the murders.

Judge Dupree postponed any decision on the psychiatric issue. As the trial progressed, assistant prosecutor Murtagh raised the psychiatric issue at subsequent bench conferences. For example, “we think this whole psychiatric thing is a can of worms, Your Honor. It is going to prolong the trial.” At a later conference, he said that Dr. Robert Sadoff was, “not competent, and will only confuse the jury.” This was, despite the fact, that Sadoff was a founder of the American Board of Forensic Psychiatry, a leader in the field.

Judge Dupree was reported to have concurred with prosecutor Brian Murtagh, adding, “congress had erred in allowing psychiatric evidence at trial.” In other words, the judge’s personal viewpoint on psychiatric testimony, being disallowed into evidence, was firmly entrenched.

On Thursday, August 9, 1979, as the trial was drawing closer to its conclusion, assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh again approached the bench. He informed Judge Dupree that he had retained the services of a forensic psychiatrist and that this expert had advised him that MacDonald’s 1970 Rorschach Test (a subject’s reaction to the inkblots) was never completed. This was untrue and a lie on the part of the assistant prosecutor, as the prosecution had never seen the test results. But, Murtagh weighed-in, “if psychiatric testimony is going to be offered by the defense, we would move the court to order the defendant to submit after court, perhaps on Monday, to any, and all psychiatric or psychological testing.” He proposed that if the court was going to allow psychiatric evidence then in all fairness the defendant would need to submit to, “an impartial evaluation by a neutral psychiatrist.” In the end, Judge Dupree agreed with the prosecution.

This was the sixth psychiatrist in the case. The previous five had all given MacDonald favorable reports. Judge Dupree had indicated clearly his dismissive attitude to psychiatric testing. But, if the defense psychiatrists, Sadoff and Halleck and their psychologists were to testify, then MacDonald would be compelled to be reassessed by a psychiatrist of the prosecution’s choosing. Supplementary defense attorney’s Wade Smith and Michael Malley confided to Jeffrey MacDonald their distrust. Their legal instincts led them to suspect foul-play and a set-up.

The government psychiatrist chosen to examine MacDonald was Dr. James A. Brussel, a man in his seventies. To aid him in the task, psychologist Dr. Hirsch Lazar Silverman was hired. Defense attorney Bernard Segal prepared a written statement of the terms upon which the examination would proceed. He made the stipulation that the details elicited from the assessment, were to be held in strict confidence, and only divulged if Judge Dupree allowed all psychiatric testimony into evidence.

The prosecution assured the defense that Dr. Brussel was a person new to the MacDonald case. This however was untrue. The army CID had recruited Brussel in early 1971 after psychiatrists had tested MacDonald and found him to be of sound mind. The CID agents had, in 1971, shown Dr. Brussel the crime scene photographs and autopsy reports along with statements allegedly given by MacDonald. After considering what he was shown, Brussel advised the agents that he believed MacDonald had murdered his family. The point here, is that this supposedly new psychiatrist to the case, had eight years earlier been hired by the prosecution and had decided then that MacDonald was guilty.

Dr. James A. Brussel was described as, a gun-toting celebrity psychiatrist and came with a flamboyant reputation as being a “psychic criminalist,” allegedly capable of describing a suspect without the need to interview the perpetrator or view the crime scene.

Once the examination was concluded, MacDonald divulged to defense attorney Segal that Brussel had asked mainly forensic questions which related to the crime scene. MacDonald reported that, “at no time did Dr. Brussel discuss my childhood, my marriage with Colette, my feelings about my children, my capacity for violence, my aggressiveness.”

Dr. Brussel’s report of the examination was handed immediately to Judge Dupree, violating the terms the prosecution and psychiatrist had agreed upon, prior to the examination (that the details were not to be disclosed to anyone, until such time, Judge Dupree would allow all psychiatric testimony into evidence). Judge Dupree read the report. The summation said that, “Dr. MacDonald may well be viewed as a psychopath subject to violence under pressure,” and “Dr. MacDonald in personal and social adjustment is in need of continuous, consistent psychotherapeutic intervention, coupled with psychiatric attention.”

Assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh pointed to the variance of the psychiatric findings, even though five psychiatrists had found MacDonald did not have the personality type to have murdered his family, whilst only Dr. Brussel had judged him to be a killer. Brian Murtagh then raised his previous view, that all the psychiatric testimony be disallowed as evidence. Judge Dupree agreed stating that the psychiatric testing would only confuse the jurors and ruled that it was, “not cognizable to the ordinary human mind not versed in psychiatry.” Dupree ruled that the psychiatric testing, “will not be admissible.”

Years after the trial, Dr. Emanuel Tanay, a clinical professor of psychiatry at Wayne State University and an expert in his field and an author on homicide, in a review for the Journal of Forensic Sciences stated:

“The prosecution’s case against MacDonald was in large measure built upon character assassination. Every possible indiscretion that Dr. MacDonald had committed over his lifetime had been paraded before the jury time and again. However, psychiatric testimony offered by the defense was kept out because it was ruled to be “character testimony. This was clearly unfair.”

With the psychiatric testimony ruled inadmissible as evidence, the prosecution and the defense delivered their final summations.

On August 29, 1979, Jeffrey MacDonald was convicted on two counts of second degree murder in the deaths of his wife Colette MacDonald and elder daughter Kimberley MacDonald and on one count of first degree murder in the death of his younger daughter Kristen MacDonald.

Prison

Jeffrey Robert MacDonald was driven across the country and imprisoned in California, at San Pedro’s Terminal Island Correctional Institution, in October 1979. On July 29, 1980, after serving about a year, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned his conviction, on the grounds he had not received his rights to a speedy trial. He was released from prison and remained free for a year and a half. He resumed his busy lifestyle working as director of emergency medicine at St. Mary’s Medical Center in Long Beach.

In the meantime, MacDonald’s work colleagues at St. Mary’s rallied in support. They were joined by Los Angeles law enforcement officers. MacDonald had always made it a priority that he be called to the hospital, even in the middle of the night, from his home, should an officer be injured in the line of duty. The psychology behind this directive, is that his own family was murdered in the middle of the night, and being an emergency physician, he was alert to the importance of a critical response time.

The support group paid for a blimp, which floated across the sky, along the coastline from Long Beach to Malibu, trailing a public relations message with the words, “The Rock”. If one was standing on the shoreline of Santa Monica beach, on that breezy winter’s day, the words waved about, low in the sky, directly in front of them. Citizens would have been stymied to understand what the words meant. In-fact they referred to MacDonald’s ability in the emergency department where he worked. Such was the strong faith his fellow colleagues had in his clinical expertise, and in his leadership.

During this brief period, when MacDonald was a free man, the Supreme Court reviewed the speedy-trial law and changed the starting time from the date a person is charged to the date they are indicted.

MacDonald was charged on May 1, 1970. The new speedy-trial law meant his start date was now moved forward to January 24, 1975, at the time he was indicted by the Grand Jury. The change to the speedy-trial law sealed the fate of the defendant, and in turn the High Court convened to review his case.

On March 31, 1982, the High Court justices voted six to three against, and the appellate court’s ruling and the speedy-trial win were rescinded. Jeffrey MacDonald was returned to prison, where he has remained for the last 35 years.

Conclusion

Without any doubt, the trial is where everything went wrong for the defendant.

Judge Franklin T. Dupree Jr. had blocked most of the issues at trial upon which the defense had built its case. The “Rock Report” which resulted from the Army Article 32 hearing and which had exonerated the defendant in 1970, was disallowed. The defense had not been granted permission to examine the FBI and CID laboratory notes and official reports that came from the scientists and lab technicians who had tested the physical evidence (these documents were examined years after the trial through the Freedom of Information Act, and they disclosed crucial physical evidence which came from an unknown source and which pointed to the likelihood of intruders having been present in the murder apartment, and they also disclosed the discrepancies and opposing findings between the FBI and the CID). These key findings were not known to the defense and were never heard by the jurors. The psychiatric testimony was ruled inadmissible. The confessions of Helena Stoeckley and the testimony of the witnesses to her admissions of involvement and that of her associates was ruled inadmissible as evidence.

Assistant prosecutor Brian Murtagh made an ethically questionable decision by not disclosing the new, crucial findings, pertaining to the physical evidence (the discovery of the black wool fibers which were found clinging to the mouth and torso of Colette MacDonald and the two black wool fibers found on the backyard club of wood used by her killer to fracture her skull and both arms and fracture the skull of Kimberley MacDonald, nor the blue acrylic fiber found in the right hand grasp of Colette MacDonald). This new evidence came to light, by his own probing (by asking the FBI to re-examine specific fiber material), only months prior to trial. Brian Murtagh told no one of the new findings, apart from chief prosecutor James Blackburn.

Chief prosecutor James Blackburn ignored these findings when he delivered his final summation before the jury. He asked the jurors how it came to be that two blue pajama threads were found on the murder-club outside in the backyard if MacDonald had not used it himself to strike his wife. He said this, after being told by Murtagh, that these two threads were in-fact made of black wool. No fibers from the blue pajama top were discovered on the murder club.

James Blackburn struck a second critical blow to the defense in his final summation. MacDonald had claimed that he had lain at the west-end of the hallway before regaining consciousness. Blackburn asked the jurors, “How much Type B blood, if any, was found here?” He was pointing to the part of the hallway on the chart which showed the interior floor-plan of the murder apartment. There was none that the defense or jurors were privy to know about. But, found discovered in documents released through the Freedom of Information Act years after trial, was a CID laboratory report made in 1972 and which listed as Exhibit D-144 (a blood spot, found in the precise spot where the defendant claimed he had lain. The analysis note indicated that it was most likely Type B blood).

None of the above were heard by the jurors.

Defense attorney Bernard Segal pointed out years later that, “the lack of disclosure allowed the government’s case to undergo a drastic metamorphosis.” (this referred to the time that had elapsed since the Army Article 32 hearing in 1970 until the time of the trial in 1979).

Jeffrey MacDonald was asked in prison in the early 1980s, whilst a guest on the “60 Minutes” television program, about his conviction. He said that he was found guilty, “after 9 years of changed evidence and an orchestrated trial.”

This article is the final installment of a 3-part series.

Bibliography

Books:

- Kelly, John F., and Wearne, Phillip K. Tainting Evidence: Inside the Scandals at the FBI Crime Lab. New York: Simon and Schuster Inc., 1998.

- Morris, Errol. A Wilderness of Error: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald. New York: Penguin Books, 2012, 2013.

- Noguchi, M.D. Thomas T., with Joseph di Mona. Coroner at Large New York: Penguin Books, 1985.

- Potter Jerry Allen, and Bost. Fred H. Fatal Justice: Reinvestigating the MacDonald Murders. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc., 1995.

![Inside The Brain of a Serial Killer [Infographic]](https://www.crimetraveller.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/skbrain1-100x70.jpeg)