Professor of Forensic Psychology Katherine Ramsland is one of the leading voices in understanding the criminal mind. With 59 books published including textbooks and case-studies, she is an expert in her field and a respected authority who regularly delivers training workshops to law enforcement and works to help educate through lectures and talks.

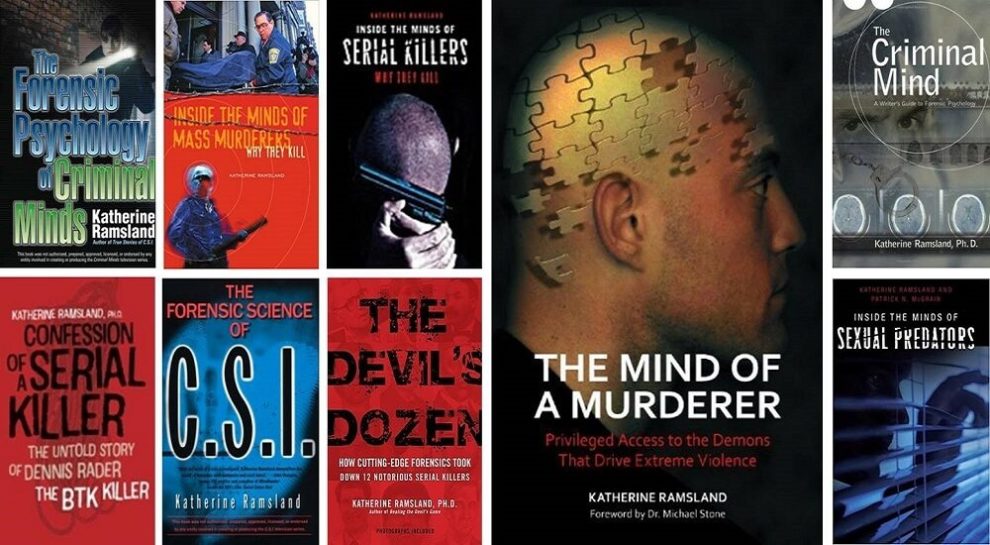

She has co-written books with former FBI profilers John Douglas and Gregg McCrary and consulted on TV shows and documentaries. Her own books include: The Mind of a Murderer: Privileged Access to the Demons that Drive Extreme Violence, Inside the Minds of Serial Killers, The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds, The Criminal Mind: A Writers Guide to Forensic Psychology, Inside the Minds of Healthcare Serial Killers and Inside the Minds of Mass Murderers.

Open-minded and curious, she is a dedicated and prolific writer who carries out in-depth research on her topics to deliver informed, educational and fascinating work, making her not only a best-selling author but a respected academic.

Katherine Ramsland is currently based at DeSales University in Pennsylvania where she is Director of the Master of Arts Program in Criminal Justice and also teaches courses in forensic psychology. She has earned three Master’s Degrees in Forensic Psychology, Clinical Psychology, and Criminal Justice alongside her undergraduate degrees in Philosophy and Psychology, plus a PhD in Philosophy. A range of insightful articles can be found on her blog Shadow Boxing on Psychology Today, covering topics like dangerous minds of predators, serial killers, and love and murder, as well as reviews of recently published true crime and forensic books.

Q&A With Forensic Psychologist Dr. Katherine Ramsland

Katherine Ramsland has very kindly found the time in amongst her writing and teaching to discuss her work in the field of forensic psychology with me here on Crime Traveller.

Q. When you first started your career studying for your degree in Philosophy and Psychology at Northern Arizona University, did you always want to teach academically and be an author?

KR – First, I had hitch-hiked into Flagstaff with no intention of going to college. I was visiting friends for the summer and decided to take a philosophy course. It changed my life. Growing up, I did not aspire to be an educator or an author. I wanted to be an athlete or an artist. Then, at age 15, I broke my arm and leg. This ended the athletic career. In the process of recovery, I wrote a 1,000-page novel. Still, that didn’t hook me into writing. I didn’t go to college until I was 21. So, academics was never my dream as a kid. But then things happen, and life changes you.

Now I have four graduate degrees. Something similar happened with writing. After writing my first book, I hated the experience so much I never wanted to write again. It was an academic book. Then I wrote a commercial book and loved it. Now I’ve published 59 books with two more coming up. What happens is not necessarily what you expect. It’s probably a good thing that you can’t always get what you want. I got much more than I wanted.

Q. You also have three Master’s Degrees and a PhD, how did you fit all these in and what has achieving these qualifications gained for you in terms of helping your career move forward?

KR – My journey has been circuitous. I tend to have one foot in and one foot out of everything I do, so I live double lives. Many of my books have nothing to do with academics, but I’ve also been in a position to design courses that would go along with my interests, like death investigation and serial murder. Yet also, one course that I teach, Psychological Sleuthing, inspired two of my books. When you love to learn, it’s not hard to find time to achieve these things. The books I have most loved to write are those that took me into worlds I didn’t know. My forensics career started with writing for the Crime Library website, which became part of Court TV. The more I wrote, the more of an expert I became. But the important thing to know is that I didn’t plan it; I followed my opportunities, fueled by my love of learning.

Q. In your role at DeSales University you have taught courses on Dangerous Minds and Anti-Social Behaviour, Behavioural Criminology and Forensic Science in the Courtroom amongst others. What do these courses bring to your curriculum?

KR – I designed the forensic track in our psychology program and was part of the design team for the Master of Arts program in criminal justice that I now direct. For the field of psychology, forensics applies research from clinical, cognitive and social psychology to the legal arena, and the things we learn in forensic psychology about such things as eyewitness memory, insanity, mental competency, and risk evaluation can be taught to aspiring investigators and attorneys. Most criminal justice programs now realize that psychology is a significant part of the process but few in that field have had training in such things as clinical and cognitive psychology.

I was a clinician for a few years, but more importantly, I see the need to show investigators about how human cognition works when they are making decisions about cases. Observation and interpretation are full of subjective factors that can send them in the wrong direction and result in wrongful convictions. I’m proud of the tracks I’ve created at my university and am happy that the courses I teach give me an outlet to apply what I learn from research and consulting. I work on death investigation teams, so I take that into the classroom. I research extreme offenders and then teach others about what I learn. It works out nicely.

Q. You seem to be a person who enjoys being busy with many projects on the go at once. Writing is an exhausting task, how do you manage to stay focused and productive and able to carry out in-depth research with so many continuous commitments?

KR – I prioritize. I do what must be done for the academic side as efficiently as possible and I devote the rest to writing. Because writing draws me, I don’t have to motivate myself. It’s what I want to do. I don’t find it exhausting. The research part is probably the most exciting, because it’s about discovery and learning new things. That’s actually energizing. And the more I write, the more prepared I am with information for future projects. I know when I’ve reached the point where I can’t take on one more thing. It’s a certain feeling of stress that feels too full, like I can’t eat everything on my plate. So then I start turning things down. It all seems to work out. I’ve missed some sleep at times, but I’ve never yet missed a deadline.

Q. You have written and collaborated on a number of books on the realities of working as a Forensic Psychologist and the role of forensic science within a criminal investigation, such as “The Forensic Psychology of Criminal Minds” and “The Real World of a Forensic Scientist” with Dr Henry C. Lee. Do you think the media and television often portray the role quite differently giving the public an inaccurate profile of what a Forensic Psychologist actually does?

KR – Commercial media is primarily about entertainment. When reality doesn’t deliver this, they make it up. Viewers need to understand that everything is done in the media to keep them hooked, including the news media. Reality is rarely like that. Even writing a book about cases means we have looked through years of daily drudgery to find cases with intriguing components. Of the ten or twelve you might see in an investigator’s casebook like The Unknown Darkness, there are many more that wouldn’t make the cut. I’ve worked with Hollywood quite a lot, including CSI. For example, I participated in an episode about forensic hypnosis. The writers had the wrong idea about how hypnosis works. (I had used this tool as a therapist.) To their credit, they listened to my explanation and changed their story line. But I’ve also watched a writing team decide that their idea works for a plot, regardless of what’s real, and they’ll do what they want.

Viewers must understand that the primary agenda of drama is to keep them engaged, not to teach them how things really are. Those writers who can use real elements in entertaining ways are to be commended for their integrity, but plenty of readers don’t really care about such things as whether making a silicone mold of a wound won’t actually yield the shape of the knife. They love the ‘wow’ factor. In the field of forensic psychology, especially, there’s a lot more drudge than ‘wow,’ so scriptwriters add elements that exaggerate or fictionalize the psychologist’s role.

Q. There has been a great deal of debate in recent years about neurocriminology, the developments in brain imaging and what this may be able to tell us about the criminal mind. The notion of structural or functional disorders within the brains of criminals and especially those who kill is a complex one. Do you find this field an exciting progression in science or one you feel should proceed with caution, especially with how such evidence is presented in the courtroom?

KR – One problem in this area is the rush to make news. Often the research fails to support some of the claims we see. Watch what happens in court if you want to know the progress, not what’s reported in pseudo-science articles. It is true that neurocrminology is making important strides in such areas as psychopathy, deception detection, adolescent perception, and risk appraisal, but for every practitioner who believes that he or she can testify about neuro-causation, there is one who can show why this is not true. In this field, it’s still expert vs. expert in terms of definitive interpretation, which means that the science is not solidly established yet.

I do see the day coming when there will be sufficient weight of evidence to shift the legal system’s decision-making. We’ve already seen it in court decisions about adolescents. It’s not far away, but it is not yet at hand. When it does arrive, it will be a sea-change, and it will affect not just the courts but the entire correctional system. We need to prepare. If we give one killer a pass because his psychopathic brain is dysfunctional, imagine all the convicted offenders who will demand a new day in court! Still, I will tell you that there are some very impressive researchers working to make psychopathic brain dysfunction into a legal defence. It requires one charismatic, articulate expert with impressive evidence to break through the current legal impasse. That person is already out there.

Q. There have been some especially harrowing cases of juvenile violence and adolescent murder recently whether by teens acting alone or in some form of relationship with another. How do you feel about these types of juvenile crimes and how the criminal justice system can deal with them in terms of punishments and the possibility of rehabilitation for these young offenders?

KR – One interesting program has been ongoing at the Mendota Juvenile Treatment Center in Wisconsin. It’s an intensive program that uses decompression therapy, and its ability to reduce repeated violence in teen offenders is impressive. The program is expensive, but presumably saves money on the long-run. A few other programs that use forms of cognitive-behavioural therapy have also seen positive results.

The kids who are considered at risk for becoming adult psychopaths are the most difficult, because punishment fails to deter them or teach them anything. Effective treatment exploits their self-interest to guide them toward prosocial behaviour. Such potentially dangerous kids can be identified at even younger ages, so intervention is possible. We can’t entirely eliminate violence in youths, but we are able to spot a collection of red flags in their personal and social milieu. Rehab is provably possible, but it’s costly. Society must be willing to support it. The same is true for mentally ill adults at risk of becoming violent.

Q. What kind of forensic consulting do you do?

KR – My favourite type of consulting is doing psychological autopsies. I work with coroners and other investigators on cases that are considered equivocal, or unclear as to the manner of death. Psychological factors will play an important role if the death is a suicide, so I investigate those and provide my analysis. One of my favourite experiences was attending a coroner’s inquest, which lasted 13 hours, but I was the final witness and I was able to correct some of the misconceptions I had heard from the attorneys. They had relied on myths about suicide to make their arguments, but I had research to back up what I said. The citizens heard me. I teach other professionals about insights from suicidology, hoping to shift investigations away from myths toward a more accurate determination. I’ve even done an extensive study of suicide notes to be able to show the markers for fake vs. genuine notes. That will be in the book I publish in December, The Psychology of Death Investigations.

Q. For your book “Confession of a Serial Killer” published in August 2016, you engaged with Dennis Rader, the BTK killer, through letters and calls to try and understand more about his psychology and his development into the serial killer he became. How did you find that process and were you surprised by any of the information he revealed or what you learned about him?

KR – It’s difficult to surprise me since I’ve spent many years studying extreme offenders. But it was definitely an interesting 5-year study. I had just published a book, The Mind of a Murderer, which describes and examines a dozen cases from the past century of mental health experts who had taken the extra time to learn about an extreme offender from the offender. This meant forming a relationship of trust. And it paid off in rich material about mass and serial killers. So, I had these role models, not to mention having been the primary writer for Court TV’s Crime Library on serial and mass murder for seven years.

I structured Rader’s “dark journey” memoir as a guided autobiography. Rader would write long letters about his life, experiences, and fantasies, and I added psychology and criminology for a sophisticated layer of analysis. We would then talk about it. We read a few books and articles, and discussed how the concepts applied to him.

In addition, he had taken some psychological tests, so I included the results, and in the end, I summarized our enterprise with an overview. In addition, I posed specific questions to get him thinking, such as asking him to provide what he considered to be the top six items that were responsible for him becoming a killer.

Whenever he named other serial killers or described movies or books that had an effect on him, I researched the subjects and watched the movies in order to form productive questions. If he described places that had meaning for him, I visited them. Together, we expanded the story from mere memoir to experiential narrative. I had a chance to see his blind spots, his complicated subjective world, and the dynamics of a psychopathic, compartmentalized individual who had unique psychological buffers.

His full story also confirmed a cognitive error typical in true crime: how easy it is for us to decide from the facts we have that we know the whole story. I can’t tell you how many experts I spoke with who believed “truths” about Rader based only on partial facts. For example, everyone uses him as an example of a serial killer who was able to stop. They think he killed ten people and that’s the total of his “project” list. In fact, his project list was in the 50s, and if he had succeeded, a lot more people would have died.

Most interesting to me in this experience was documenting the development of his fantasy life and the way it moved him toward murder. He relied on role models and even on novels to devise his approach. As a teenager in the 1950s, he had aspired to become a serial killer. He did not become a killer from being abused or neglected or deprived. He became one through sexual fascination, depraved ambition, and a vividly twisted fantasy life.

Q. After 59 books and over 1000 articles written and published, you have achieved a great deal in your career already. Are there any milestones you are still aiming for and what are your plans now moving forward?

KR – One milestone is that I have turned in my last academic book, The Psychology of Death Investigation. I prefer writing commercial books and will be writing more fiction in the future. I am working on my fourth novel and I have ideas for others. Currently, I’m writing Track the Ripper, a sequel to The Ripper Letter, which places Jack the Ripper lore in a paranormal universe that joins New York with London and Paris. I have a third novel in mind for that series. I also hope to write more about cognitive forensics, an area on which I do a lot of presentations. It touches all investigations, from cold cases to serial cases to wrongful convictions. In Forensic Investigation: Methods from Experts, I included a chapter about it, but I’d like to expand this into a series of articles that show how various cognitive conditions have affected investigations, both positively and negatively. These articles would be practical, not academic, and I will probably offer them in e-form.

Thank you for the opportunity to talk about my work.

Thank you Katherine for such an insightful and fascinating interview. I’ll be looking out for your next book The Psychology of Death Investigations! A thank you also to Randy Williams for the introductions to make this interview possible.

A great interview with a terrific author!

Thanks Randy! This was a fantastic opportunity and a fascinating interview with such excellent responses from Katherine. Very inspiring too!

Hi there! Such a wonderful write-up, thanks!