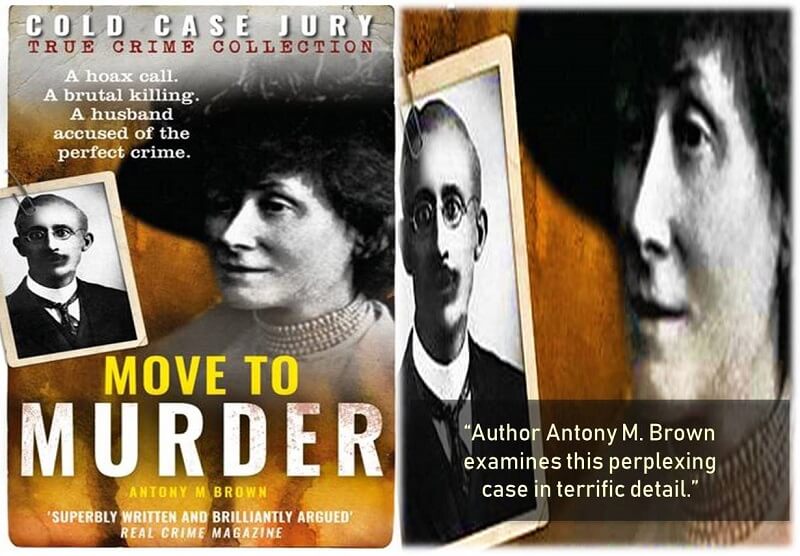

In one of the most famous cold cases in British history, the murder of Julia Wallace in Liverpool in 1931 still has people pondering on who was her killer. Her husband William Wallace was arrested and convicted of murder, however, after just one month his conviction was quashed as it was determined that the case against him could not be proven. If William Wallace did not murder his wife on that January evening, then who did?

This case is full of loose ends and open questions. The curious phone call to William Wallace while he was at a chess club the night before the murder. The young Gordon Parry, a work colleague of Wallace, who may have been seeking revenge and most curious of all, a crucial milk delivery on the night of the murder, where the timing may hold the key to William Wallace’s involvement.

“William Wallace is the spider hanging at the centre of this tangled web.” – Antony M. Brown

In 1911 William Wallace was employed as a Liberal Agent for the Ripon Division in West Yorkshire, employment which led to meeting his future wife, Julia Dennis. They married in March 1914 but struggled when the First World War forced Wallace out of his political role and into a relocation to Liverpool and a job in insurance.

In 1928 he fell ill with bronchitis and the young man who covered for him, Gordon Parry, plays a crucial part in this tale and may well have been involved in the murder just three years later. When Wallace returned to work he discovered Parry had been helping himself to cash. A discovery he reported to the authorities. Did this give Gordon Parry motive for revenge?

William Wallace was a well-liked and respected man by most accounts, although his personality and temperament according to some was “calculating and despondent”. Wallace liked details, he liked facts and for everything to be correct, in its place, and accounted for.

The Murder of Julia Wallace

On 20 January 1931, Julia Wallace was found dead in the parlor of her home by her husband William Wallace. Julia’s death was brutal and violent, described as a “frenzied attack of terrific force”. She had been beaten around the head with an iron bar, a weapon which has never been found. Under her body was a raincoat later established to belong to William Wallace. The house was in disarray and four pounds had been stolen from Wallace’s collection box.

In Move To Murder, Antony M. Brown focuses attention on a curious phone call made to a chess club William Wallace attended the night before the murder. A call that has come to be at the center of this mystery.

A man calling himself R.M. Qualtrough called a restaurant where a chess club regularly met with William Wallace as a member. The man asked to speak to Wallace who had not yet arrived. He then gave an address and asked for Wallace to meet him there at 7.30 pm the next evening. This is a meeting that never took place with William Wallace on a wild goose chase looking for an address that didn’t exist. However, this depends on which account of what happened that night that you believe.

Was this a call to lure William Wallace away from his home to allow for the uninterrupted murder of his wife? Or was it William Wallace himself, making a bogus call to give himself an alibi?

“Although the murder of Julia Wallace appears motiveless, it is easier to accept that there might have been a motive to move Wallace to such savagery. There are jagged rocks that lie beneath the most serene waters of marriage.” – Antony M. Brown

A second most curious factor in the murder of Julia Wallace was the milk-boy delivery on the night of her murder. 14-year-old Alan Close delivered milk that evening and spoke with Julia who answered the door.

In his original statement he claimed the time was 6.45 pm, however by the time the case got to trial, this had changed to an earlier 6.30 pm. It is not known why these timings changed and they may simply have been a reconsideration of timings from his original statement to the trial, and entirely innocent.

Their significance, however, is high and of most importance for William Wallace. It is known he left his house that night at 6.48 pm to attend his mystery meeting, therefore if Julia was still alive at 6.45 pm witnessed by the milk-boy, three minutes is not sufficient time by anyone’s calculations for William Wallace to have killed his wife, cleaned himself up and staged a robbery.

If however, Julia was seen alive at 6.30 pm, another fifteen minutes become available and the possibility of William Wallace having the time to commit the murder becomes active once again.

For those interested in historical true crime and those who love a true murder mystery, this is a case not to be missed and a book that will guarantee a thought-provoking read. Only one thing remains, who was most likely responsible for the murder of Julia Wallace in 1931? Move To Murder is a fantastic example of an intriguing historical murder case being explored in full detail. No stone is left unturned when digging through the evidence from trial transcripts, witness statements, and the numerous publications which have appeared surrounding this case over the years.

Move To Murder is part of the Cold Case Jury series of historical true crime books by Antony Matthew Brown. Check out the full series here on Amazon.