“Creator of the famous Obedience Experiments and originator of the ‘six degrees of separation’ theory, Stanley Milgram transformed our understanding of human nature.”

Hate and fear are two of the most powerful weapons this world has ever and will ever have. The massive murder machine that was Nazi Germany and its alliance knew how to manipulate these feelings in a way that started a series of events that the world has never recovered from, World War II. Thomas Blass, the author of this book, is a Professor of social psychology and has enjoyed a lifelong interest in not just studying Stanley Milgram’s experiments but also what made Milgram really tick, what excited him, his passions and something that Milgram guarded very well when alive; his personal life.

The prologue helps us understand the background to Stanley Milgram’s love of science and what made him carry out one of the most famous social psychology studies ever undertaken: The Obedience Experiments. Blass shows us in Chapter One that little Stanley Milgram came into this world in The Bronx in New York City in the early 1930’s to Jewish parents who were Polish emigrants. Although World War Two had made its mark on young Stanley, he always turned to his love of science to cheer him up and he loved playing some sort of trick on his friends. Once he blew up the Hudson river bank where he lived leaving smoke and rubble everywhere and one very angry mum.

He would often carry out one of his ‘infamous’ experiments on one of his cousins making him think he could hear voices whilst suspending him between Stanley’s and Joel, his brother’s, bed. If some explosion happened everyone in the neighborhood knew it would be Stanley Milgram and his chemistry set.

At his Bar Mitzvah though, when a young Jewish boy is said to become of age, Blass explains that Milgram gave a very moving speech about his Jewish roots and how the war had affected him. In part, he said: “I do not know whether I shall be able to cherish this heritage in the same way as my parents did throughout their lives. But I shall try to understand my people and do my best to share the responsibilities which history has placed upon all of us.”

Stanley Milgram was a very intelligent boy and man. When Milgram was in high school, his principle had him tested for his IQ and it was no surprise when his results came back at the highest end of the spectrum at 158. In the 1950’s university did not happen unless you were rich or you were extremely lucky to get a scholarship. Milgram was a determined person and he had his sights set not just on any university but the one and only Harvard!

Psychologists around the world in the 1950’s and 60’s were desperately trying to explain why atrocities like the gas chambers and mass genocide took place and why neighbor became enemy of neighbor. These are just a few of the thousands of methods used to inflict pain and death in World War Two and why crime and murder were rife across America.

Chapter Four shows one of his first Professor’s named Solomon Asch, a very stern individual, had Stanley Milgram appointed as his assistant. Asch was carrying out what was to become known as the ‘line experiments’ to see if any of the group of students would be willing to go against the grain and stand out by not agreeing with the majority on which line was the longest.

Although a simple experiment, the results were shocking. Almost all students went along with the crowd. This struck young Stanley who was now in his early 20’s. He felt it needed a further explanation but Asch was adamant that he was not prepared to take this study further. This caused a massive rift between them as Milgram was not used to being upset by Professors.

He graduated at Harvard University both with a Bachelors and Masters in his field of psychology. He worked at Harvard for a number of years until he moved to Yale University. It was here his most famous experiment took place.

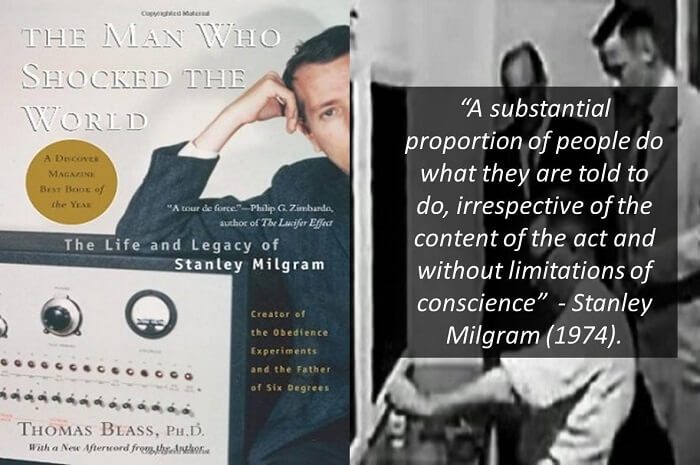

The Milgram Experiment

After getting permission from Yale and his sponsor, nearly a year in setting up and recruiting went by as Stanley Milgram was extremely meticulous. He laid out his lab, personally chose his assistants and made the mocked up equipment.

In his experiment, a person, the ‘Teacher’ was asked to give an electric shock to another person who they had never met before every time they got a wrong answer to a question. Milgram said, “the results were terrifying and depressing “. By all accounts, participants were under the impression that they were real electric shocks and that the ‘Learner’ had a heart condition and on numerous occasions screamed in pain and said that “he did not want to continue”:

Here is a small excerpt of just one participant’s actions.

(Before you carry on, I want you to put yourself in the ‘Teachers’ place)

Teacher: COOL – day, shade, water, cave. (Awaits response…..)

Learner: Silence – No answer

Teacher: Incorrect ZZZZAP 390 VOLTS

This continued to past what the Teacher thought was 450 volts of electricity. The experimenter then had to stop the test. This was not a one-off. The majority of participants in each experiment, except two of them, carried on past 150 volts and up to 450 volts and obeyed the ‘experimenter’.

How did you feel as the ‘Teacher’? Would you have ‘electrocuted’ an innocent man with a heart condition?

Imagine now the tables have turned. If it was really happening to you, how would you feel? When asked this question, most say no they wouldn’t do it, but in Nazi Germany, and many places since, people knew who they were killing or experimenting on and had the same zeal and passion for their “job” as did these Teachers. In one of the experimental conditions, a Teacher who was a very strong man, grabbed the hand of the Learner because he had ‘passed out’ (this being acted). The Teacher shouted and swore at the man and jammed his arm and hand down hard on the metal connection plate before ‘electrocuting’ him.

Overall, the results and conclusions were so damming to the American population, and to the world as a whole, many psychologists declared Stanley Milgram’s experiment unethical, despite Milgram going far beyond what he had to do to set up and monitor his participant’s before and after. If anything, ethically it was a triumph. No one was hurt in the experiments carried out by Milgram and he debriefed or reassured his participants that it was staged. If they wanted to, they could discuss what had just happened with a clinical psychologist or psychiatrist or directly with Milgram himself at any stage.

Instead of the world applauding him for discovering something that was not understood before, they vehemently turned against him. Blass shows us in Chapter Seven, that there was no reason for their actions, although Blass himself does have some doubts regarding some of the ethics involved.

I think page 125 speaks for itself. The chart shows that only 3 out of 856 participants regretted taking part. No one was ever hurt and Stanley Milgram and his researchers made sure that everyone was happy before they left, which included reuniting them with the ‘learner’. Milgram checked on them 6 months and 12 months later and not one psychologist at the time ever did this.

He was also instrumental in setting up ethic committees in universities. The hate he received broke not just his career but also his heart. Blass’s book tells many happy and sad stories that occurred throughout Stanley Milgram‘s life. His love (Sasha his wife and his children) and his passions (too many to mention throughout his student life in university), his moments of need and depression.

On December 20th 1984 at the age of 51, Stanley Milgram passed away with his fifth heart attack with both Sasha and Irwin Katz, his lifelong friend and colleague, by his side. The world today is not only missing a kind loving man but a truly brilliant scientist, father and friend.

Thomas Blass’s book has been acclaimed throughout the world, not just by the psychology and scientific communities but by its public readers to. Stanley Milgram’s final note he left for a student on the day he died sums up the man that shook the world:

“The whole world

Is a very narrow bridge

But the main thing to recall

Is to have no fear at all.”

You can purchase a copy of The Man Who Shocked The World at Amazon.

Meet the Reviewer: My name is Benjamin Thompson and I’m a BSc (Hons) student in Forensic Psychology at The Open University. I have always wanted to go into Forensic work and wish to continue my studies so that I can practice as a Chartered Forensic Psychologist. I am also proud to be a registered member of the British Psychological Society.